Fighting to the finish

|

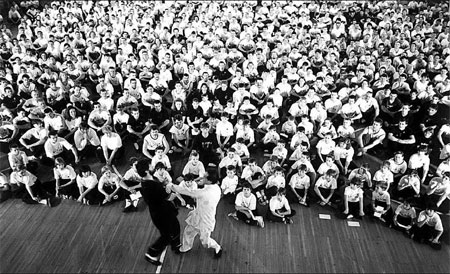

WingTsun master Leung Ting (right) during a demonstration at an overseas class. |

Mention Bruce Lee and you are likely to get an animated reaction, maybe even a Lee-style sweep of the leg. Bring up the name Leung Ting, however, and chances are you will draw a complete blank.

Yet the two men share a common teacher - the enigmatic Ip Man who popularized the art of WingTsun (also known as Wing Chun) and whose life story was the toast of Chinese cinema late last year.

While Lee may be the perfect catchline for a belated biopic of Ip, it is through a decidedly low-key Leung that the WingTsun master, who died 27 years ago, commands a presence in the lives of students of this martial arts today.

On entering Leung's class, held every Saturday night inside a nondescript building in Yau Ma Tei, Hong Kong, every one is required to bow toward a black-and-white portrait of Ip looming in the middle of the room.

They then make a 90-degree turn to pay respect to the picture of another man - a young and broad-chested Leung in white kungfu robe. That is, of course, if the master, who is in his 60s, is not present in person. For the students, the ritual has special meaning: Leung is the last closed-door student of Ip and thus, by the age-old tradition of Chinese kungfu, the direct descendent of a long and triumphant lineage.

"Usually, when a kungfu instructor closes his door, it means that he has retired from teaching," says Leung who, after practicing WingTsun for seven years, became Ip's student in 1968, when the late master was already 75 years old.

Looking back, Leung says: "He was always dressed in a long gown and a pair of hand-sewn Chinese shoes.

"If there was any air to him, it was certainly not the vainglorious kind, but rather, a bookish charm derived from his early immersion in traditional Chinese education."

Leung feels deeply indebted to his teacher for showing him the intricate yet often over-looked footwork of WingTsun, and teaching him all the 116 attack and defense moves performed on a wooden dummy.

|

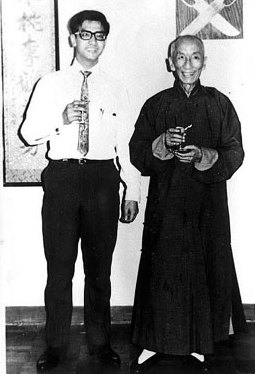

A young Leung with his master Ip Man, upon the opening of his first WingTsun school in HK. Photos courtesy of Leung Ting |

On one occasion, an apparently bemused Ip, after seeing a picture of Leung in competition, pointed out that it would better for him to "wear trousers instead of shorts". These days, one can see no shorts in the classroom where Ip once presided.

However, it would be wrong to assume that a respectful Leung has been living happily in the shadow - and aura - of his late master. "Ip was the first person to each WingTsun openly. So for me, propagating this unique art is the way to follow in his footsteps," he says.

Before Ip, WingTsun was somewhat mysterious even if a much celebrated martial art. It has now grown into a global phenomenon, with more than 3,000 training centers scattered across the world under the banner, Leung Ting's International WingTsun Association.

The secret? "They trained disciples, I train instructors," says Leung, reflecting on the ancient tradition where a kungfu master trained and lived with his students and "kept them for their lifetime".

"The idea that a master must 'hold back' from even his dearest student in order not to be 'outdone' was entrenched. It caused immense frustration, grudge, even despair," says Leung. "If Chinese martial arts are to survive outside the projection room of the cinema halls, all this will have to change."

A typical Leung class is made up of hundreds of practitioners, all clad in specially-designed black T-shirts bearing the WingTsun logo, surrounding Leung in the center, dressed in white.

The sight is overwhelming, and reminiscent of days when an entire neighborhood in some southern Chinese town came out to launch kicks and deliver punches during a break from farm work. At a time when Chinese martial arts seems to be stepping into the sunset, Leung has aroused a new wave of kungfu fever.

But before all this, Leung remembers Germany, which he visited back in 1976, invited by an admirer whom he had met only through letters. "The man was called Keith Kernspecht, and only after my arrival did I realize that he was also a karate practitioner and in fact the first person to introduce karate to the German police force," says Leung.

It would not be the last time Leung found himself face-to-face with a kungfu professional eager to be won over yet harboring absolutely no illusions. "I had to fight, and fight hard, for myself, for WingTsun and for Chinese martial arts," he says.

And not all people are well-intentioned.

One such trouble-seeker was a burly black US Army veteran named Richard Guerra, known by his fellow soldiers as "Tiger". Charging onto the stage in the middle of a demonstration given by Leung in California in the 80s, the karate black-belt demanded a duel.

However, what had first promised to be ferocious showdown between two kungfu men was cut short as Leung entered the fight with no hint of aggression, and turned the tables. With wrists and limbs as lithe and slippery as an eel, Leung proved ever elusive for his opponent, who found Leung's lightning strike hard to evade.

"WingTsun is not about intimidating, it is all about engaging," says Leung. "At the heart of it lies a genuine sense of humility - always take your enemy seriously."

However, what he didn't know at the time was that Guerra was actually a "wounded man", haunted by horrible memories of the Vietnam War. "All the hostility could be explained by his deeply disturbed mind," says Leung. "After the fight, he asked to be my student, and eventually managed to find peace with himself."

Many of Leung's overseas students have later become his most ardent devotees, opening up regional WingTsun schools at his behest, and accompanying him on his annual world tour .

A few years ago, Leung received a letter from an American woman, informing him of her husband's death. It turned out that the husband once learned a few moves from the master, after having suffered serious facial injuries in a vicious shooting. "He made sure I knew that our encounter more than 20 years ago had not been forgotten," Leung says. "And he did this on his deathbed."

Thanks in part to the ubiquity of his students, Leung has "penetrated" even the most secret of foreign special police and task forces. These include the FBI and US Marine Corps, SEK of Germany, RAID of France, NOCS of Italy and the Anti-Terrorist Squad of India, for whom he has designed WingTsun classes.

Emergencies have occurred, although not quite in the way Leung expected. While training Egyptian parachuters in the early 1980s, the master found his students kept missing classes. Embarrassed, he made enquiries and was told that a mini warfare had just broken out on the Egypt-Israel border.

While he does enjoy the occasional fame, Leung still prefers the quiet, uncluttered life of teaching, the latest addition to his students being his youngest son.

With glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, the thinly-built, academic-looking boy reminds Leung of his own teen days, before WingTsun "tempered and steeled" him.

"When I was young, I was very slim, which made me an easy target for street bullies," recalls the benign master.

To the utter amazement of his tormentors, every time, a greatly-outnumbered Leung fought back. Along the way, the little boy sustained a bleeding nose and a few bone fractures. But he never lost sight of a life-long motto.

"Give up, and you are a loser. Fight, and you still have a chance to win."

(China Daily 04/27/2009 page8)