Raiders of the lost art

|

Two imperial bronze sculptures, the rat head (left) and the rabbit head (right), shown in Paris before going under the hammer by Christie's. AFP |

|

Five bronze animal heads - (from far left) monkey, ox, pig, horse and tiger - looted from the Old Summer Palace, have returned to China. Wang Jiankang |

The sale of French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent's two bronze sculptures marks the start of a new fight by China over its stolen treasures rather than the end to a controversial lawsuit.

The two ancient Chinese relics, a rat's head and a rabbit's head, were auctioned for $39.5 million last Wednesday night by Christie's despite widespread anger and opposition in China.

A team of more than 80 Chinese lawyers lodged a motion in a French court on Tuesday in a bid to stop Christie's from selling these stolen relics, which were once housed in Beijing's Old Summer Palace, also known as Yuanmingyuan.

The bronzes were stolen in 1860 when Anglo-French allied invaders looted and then burned down the imperial palace.

The French court rejected the bid to block the sale on Tuesday, as was widely expected, but this decision offended many Chinese.

The dust has far from settled.

|

The original 12 bronze animal sculptures were used as a water clock by the Qing imperial family. A replica was displayed at the Old Summer Palace in Beijing last year. Ma Xiaogang |

At present, the retrieval of stolen or looted relics from a foreign country through legal and diplomatic means is based on several international conventions that China has signed. These include the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, and the 1995 Unidroit Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects.

However, the fact that the conventions could not be applied retroactively was a major obstacle to such legal proceedings, according to Wang Yunxia, a professor of cultural relics law at Beijing-based Renmin University.

"The Convention applies only to cultural objects stolen or illegally traded after it has taken effect," says Wang.

But "the non-retroactivity of the 1970 UNESCO Convention or the 1995 Unidroit Convention is no argument against pursuing the case for restitution," writes Ellie Bruggeman, an independent security and safety advisor at cultural heritage institutions based in the Netherlands, on Museum Security Network.

"I would encourage the Chinese to pursue vigorously their claim."

An estimated 1.64 million Chinese relics are owned by foreign museums, according to the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH). An even bigger number is in the hands of private collectors. Many of these were looted, stolen and smuggled out of China between the 1860s and 1949.

"Bringing them back is very difficult, as the recent Christie's case shows," says Liu Yang, one of the lawyers working to get the rabbit and rat heads back through legal means. "But we can't hold back because of difficulties."

A lawyer for the France-based Association for the Protection of Chinese Art in Europe (APACE), told the court on Monday that its aim was to "alert public opinion to the fate of numerous Chinese works stolen in the past and sold through trafficking".

"This is a major breakthrough in our difficult fight to retrieve our stolen and looted antiques and relics," says a SACH official, known only by his first name, Peng.

Peng recalls an exhibition co-organized by SACH last June in Beijing called Reclaimed Cultural Relics from Overseas.

It attracted many visitors, most of whom were more interested in the treasures that had been returned rather than in the fight to reclaim the missing pieces still outside China.

Peng says it is encouraging to see "the great concern shown by Chinese people and their increasing awareness of protecting national treasures by adopting legal measures" over the past month.

SACH archives show that since 1998, China has successfully retrieved nearly 4,000 antique pieces through donations, purchases by overseas Chinese, and legal and diplomatic means.

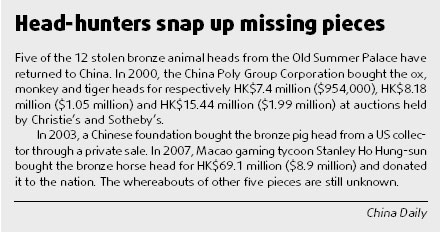

So far, five of the 12 bronze animal heads looted from the Old Summer Palace have returned to China through purchases in auctions or through donations by overseas Chinese collectors. The whereabouts of five others are unknown.

SACH has voiced its objection to both auctions and purchases of cultural relics exported illegally, including those looted in wars.

Song Xinchao, director of the SACH museum department, says while the authorities favor retrieving looted relics through legal or diplomatic means, they also welcome donations by foreign collectors.

One successful retrieval through legal means occurred in 2000 when a 10th-century Chinese wall panel, stolen from the Five Dynasties (AD 907-960) tomb of Wang Chuzhi in Hebei province in 1994, emerged in Christie's in Manhattan for auction.

Through cooperation with the US authorities, the panel was forfeited by the US customs and returned to China unconditionally. It is now part of the National Museum's permanent collection.

"The difference between this panel and the two bronze heads," says Peng, is that "the former was stolen in 1994, more than two decades after the 1970 Convention became effective."

For relics stolen or looted before 1970, "the best way to get them back is through diplomatic channels. An agreement between Chinese and foreign governments is the most effective and direct way to tackle this issue", says Professor Wang.

So far, China has reached agreements with nine countries, including Peru, India, Italy and most recently the United States, on the imposition of import restrictions on artifacts generally associated with the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods and the Shang through Tang dynasties, ranging in date from approximately 75,000 BC to AD 907.

When China acceded to the 1970 Convention and the 1995 Unidroit Convention, the Chinese government also declared that China reserved the right for the return of objects stolen or exported illegally before the Convention came into effect.

Liang Wendao, a celebrity blogger, believes that every Chinese has a role to play to bring back the nation's looted treasures. "We hate to see our historical relics looted and kept in foreign countries because they represent our history," writes Liang.

"But we have to also think that if we treasure our history enough, (we should) effectively stop the illegal trade of valuable antiques and not tear down our historical buildings.

"We need each one's effort to protect our historical relics, so that we are standing on a higher moral ground when we demand our looted treasures back."

(China Daily 03/02/2009 page8)