A diplomat's sixth sense

|

Nicholas Platt talks about his experiences in China during his recent tour with the Philadelphia Orchestra in Beijing. Zhang Wei |

As a young American diplomat, 37-year-old Nicholas Platt coordinated and accompanied the first American orchestra to perform in China in 1973 after the founding of the People's Republic of China. A year earlier, he had accompanied US President Richard Nixon on the historic trip to Beijing in 1972 that signaled the resumption of relations between China and the US.

Now 72, Platt has many backstage stories to tell about the Philadelphia Orchestra's historic trip to China in September 1973.

And the one he most likes to share is how he persuaded the orchestra's music director Eugene Ormandy at the last minute to play Beethoven's Symphony No 6 Pastoral. It was a piece Jiang Qing, wife of Chairman Mao Zedong, strongly requested but Ormandy did not like it and had not brought the score with him.

"Ormandy proposed many programs and after Jiang Qing's approval, they decided the programs before the orchestra came to China. But only half-an-hour before the Pan Am 707 landed at Beijing's airport, I got the request from Jiang Qing that the orchestra must play Beethoven's Symphony No 6," Platt recalls.

"Jiang was in charge of culture. She had her own view about Western music and Beethoven's Sixth Symphony was the only piece she really wanted.

"Thank God, I did know the symphony and the history of China, so I had to use this with the maestro Ormandy as soon as he arrived. I told him, 'The Beethoven Sixth is very important to Chinese people. First, the Chinese people love the life of the countryside which Beethoven wrote of in the music. Secondly, the scenery and feelings Beethoven describes through his music fit the special time of China now. The storm that breaks in the third movement could be considered as the 'cultural revolution' itself."

"I do not know if Ormandy was convinced but he agreed to play the piece."

The problem was, Ormandy did not have the score. Fortunately, they found one in Shanghai and immediately sent it to Beijing.

"The score was very old and had been marked and noted by Chinese conductors. Some parts could not even be figured out. But Ormandy was such a great conductor and the Philadelphia Orchestra was such a great orchestra, they performed a wonderful Pastoral and Jiang appreciated it very much."

Platt is obviously good at persuading people. The other example of his persuasive skills was the way he managed to take Ormandy, who did not like Chinese food, to all the dinners during that trip.

"The Hungarian conductor did not like Chinese food and he brought with him his wife especially to make meals for him in the hotel. I told him, in China, all the social events take place at the table. If you don't go to dinners, you will not meet people. You don't need to eat anything, you just come."

"But finally I found that he ate well every time and actually began to love Chinese food after the trip."

The reaction of Beijing audiences was very good. Platt says he saw tears in many eyes.

"Western music was forbidden during the 'cultural revolution', but the Philadelphia Orchestra's concerts opened the window for many people. Many Chinese musicians were encouraged to take up instruments again and the long-term impact of the visit was very strong," says Platt.

One of these musicians was Tan Dun, the multifaceted composer and conductor who has won the Grammy Award, Academy Award (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) and Musical America's "Composer of the Year" award.

In a public interview between Platt and Tan at the theater of Asia Society in New York, Tan told him that he heard the broadcast of one concert on radio when he worked in the countryside in Central China's Hunan province.

"'It completely changed my whole outlook on music,' Tan told me," says Platt.

Platt knows Chinese history and culture so well that people forget that at the beginning of his diplomat career, he was trained as a European specialist.

|

Left and right: Members of the Philadelphia Orchestra exchange ideas with the Chinese counterparts from the Central Philharmonic Society (National Symphony Orchestra) during their historic visit to China in 1973. File photos |

After graduating from Harvard College and Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, Platt entered the Foreign Service of the United States in 1959 and learned French and German. But his first job was to serve as vice-consul in Windsor, Canada.

He did not like that work very much and when there came an opportunity to move, Platt decided to think over his long-term career goal.

"I looked around to see what the most interesting and most expensive job was at that time. And the answer was China. In the 1960s, the Western world had great interest in China. And it cost the US government $50,000 to train a diplomat in Chinese," Platt says, half in jest.

Besides this foresight on international relations, Platt also had a personal reason; rather, a personal idol encouraged him to be an expert on China.

That man was Charles E. Bohlen (1904-74), a renowned expert on Soviet Union. Bohlen joined the staff of the first US embassy in the Soviet Union in 1934, and was serving as the Soviet expert at the US embassy in Tokyo when the United States entered World War II. During the 1950s, he served as ambassador to Moscow and was an advisor on the Soviet Union to every US president between 1943 and 1968.

"Bohlen was my father's roommate in college. I admired him so much that I decided to be a Chinese specialist, because I believe that was the equivalent of what Bohlen did in World War II," says Platt and adds, "I started to learn Chinese and I never looked back. Chinese has ever since become my basic passion."

Platt studied Chinese in 1962 and 1963, one year at the Foreign Service Institute in Washington and one year in Taiwan. In 1964, he was assigned political officer at the American consulate-general in Hong Kong until 1968, when he became China desk officer at the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. From 1969 to 1971, Platt was chief of the Asian Communist Areas Division of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research. In April 1973, Platt became one of the first three members of the US Liaison Office in Beijing and was assigned chief of the political section.

As soon as he arrived in Beijing, Platt bought a bicycle and rode it every day between the diplomats' apartment at No 1, Jianguomen Waidajie Street to the Liaison Office at No 2, Xiushui Dongjie Street where the US Embassy now sits. He even remembers the brand of the bicycle, the Phoenix (Feng Huang), the best bicycle in China at that time.

"In the first few days, I was shocked by so many bicycles on the streets. Soon, I joined the bicycle river every morning and dusk. I found it hard to stop to talk with people while walking in the streets, but on bicycles, the Chinese were not shy to say hello to me. Sometimes, the persons on the bicycle next to mine would ask, 'Are you Albanian?' I would answer, 'No, I am American'. And they would say, 'Ooh, American, I have heard of you'.

"Sometimes, we just chatted about the price of vegetables or where a wet market was. Some people even tried to catch up with me if we were not side by side."

During holidays, Platt and his family visited the Ming Tombs, the Summer Palace, the Forbidden City, the hutong lanes and bought paintings and antiques in Liulichang.

"That was a really interesting experience," Platt recalls.

Before he left Beijing in January 1974, Platt worked on many exchange events, ranging from sports and culture to academia and trade. "And among them, the Philadelphia Orchestra's visit was the high point event in the first year."

Before the concert tour, in June, Platt and his colleagues arranged a swimming team to Guangzhou, Changsha, Shanghai and Beijing. At that time, China was not a member of the International Olympic Committee and the swimmers from China and US could not compete.

He remembers the Chinese coaches asking how to "create a champion." They wanted to know the formula, the procedure and supposed the American coaches had the "magic recipe".

The American swimmers asked how far the Chinese swimmers swam every day. The Chinese answered 5,000 meters. The Americans said they swam 5,000 in the morning, 5,000 in the afternoon and also underwent weight training for two hours everyday.

"It's impossible for you to be a worker, or a farmer, and at the same time a professional swimmer, the American swimmers told them, as they knew the Chinese swimmer had to work during the 'cultural revolution'," says Platt.

In January 1974, Platt was involved in a car accident when driving to the Great Wall and he had to return to the US.

"But no matter where I was assigned, I always tried to go back to China. Dramatic changes have occurred in China in the last 30 years. I realized that as a specialist on China, one has to come back at least once every six months or one loses track," he says.

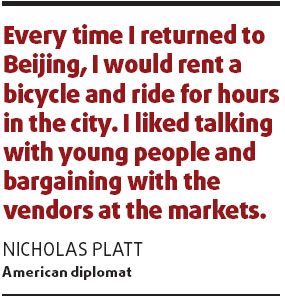

"Every time I returned to Beijing, I would rent a bicycle and ride for hours in the city. I liked talking with young people and bargaining with the vendors at the markets. Believe it or not, the Wantong Market is my favorite place in Beijing," says Platt.

And the other must-do thing for him in Beijing was to look for "pigs". Platt is an enthusiastic collector of pig-shaped subjects, such as porcelain pigs, piggy banks and pig ornaments. His apartment in Manhattan, New York, is decorated with all kinds of pigs and many of them are the Chinese antique jade pigs, porcelain pigs, wood pigs, silver pigs and Tang tri-colored glazed pigs.

His collection covers almost all the dynasties except the Ming Dynasty. And the explanation for this from the specialist on China is that the family name of the emperors of the Ming Dynasty is Zhu, which has the same pronunciation with pig in Chinese.

(China Daily 06/05/2008 page20)