All the right movies

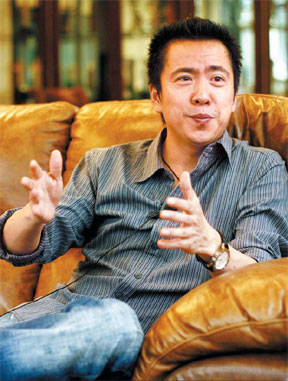

Movie producer Wang Zhonglei works from a large ranch-like homestead hidden in green woods about 30 km northeast of Beijing. From the French-style windows in his plush office, he can see the front door of his villa home and can watch his horses graze on the beautifully manicured lawns.

|

Wang Zhonglei and his brother have grown their small advertising firm into the largest private film production house in the Chinese mainland. Wang Jing |

In a city like Beijing, where the journey to work for most people often takes more than an hour, Wang's commute to his office involves a leisurely, one-minute stroll in the fresh countryside air.

The 38-year-old and his elder brother Wang Zhongjun are now enjoying a little of the trappings of their movie making success.

They have come a long way in 14 years since they opened a small advertising firm in Beijing. Today they operate No 1 privately owned media corporation - Huayi Brothers - on the mainland.

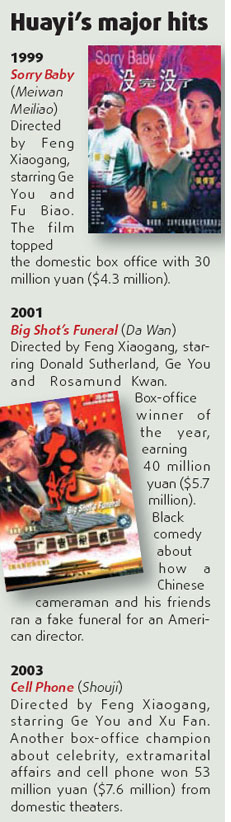

Their company is responsible for a string of hit movies, including Feng Xiaogang's Cell Phone (Shouji) and The Assembly (Jijie Hao), which have topped the domestic box office.

Their latest release, The Forbidden Kingdom (Gongfu Zhi Wang), the first film pairing Jackie Chan and Jet Li, is not only conquering China, but also making a killing overseas.

"We never considered it as a Hollywood film. It was a global film," Wang Zhonglei says.

So far the film has earned more than $40 million in North American market.

Its box-office gross in China has reached 150 million yuan ($21.4 million) since the premiere on April 24.

The story of an American teenage kungfu fan's time-travel to ancient China marks a milestone in Huayi's international co-productions.

Huayi joined the project about two years ago as a co-investor and distributor in Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Chinese companies seldom handle a film's distribution outside the mainland market, and normally sell the rights to local companies, which better understand their own regions.

Chinese companies seldom handle a film's distribution outside the mainland market, and normally sell the rights to local companies, which better understand their own regions.

Instead, Huayi set up its own distribution strategy and found partners in each region willing to follow its rules.

In Hong Kong, Huayi worked with Emperor Group and in Taiwan, it teamed with Walt Disney Studio Motion Picture International. The company also owns the film's copyright in the three regions.

Huayi invested $14 million in the movie, representing a 20 percent of the $70 million project. The company was involved in everything, from the details of the script to international sales, marketing and promotion.

Thanks to its understanding of China's policies and unique market, the brothers made helpful storyline suggestions. For example, the image of Jet Li's monk should not be too flighty or it could upset Chinese Buddhists.

Huayi also handled the film's translation into Chinese for mainland release.

Selecting such a stellar cast and crew, Wang says, was also a first for his company. The teaming of Chan and Li, the selection of director Rob Minkoff, the involvement of master choreographer Yuen Woo-ping and inclusion of Academy Award-winning cinematographer Peter Pau made up a dream team.

But the biggest leap forward, according to Wang, was the company's global vision.

"American audiences think it was a Hollywood film, for marketing in North America," he says.

"Here, people consider it a made-in-China production, because they see Li and Chan, and a loosely-adapted Monkey King story."

The biggest difficulty during the co-production, Wang recalls, was how to make the storyline acceptable to all audiences. The "family fun" strategy was the best solution.

"Some Chinese critics call it a 'banana film' which has yellow skin but is white inside," Wang says.

"Whatever it is called, I don't think this is a film for serious reviews at all.

"We designed it as a film for the whole family, just for fun."

Among China's private media groups, Huayi is one of the earliest few to test the waters of East-West cooperation.

As early as 2000, Huayi teamed with Columbia Pictures to produce Feng Xiaogang's Big Shot's Funeral (Da Wan).

It was a time of "day dreaming", Wang jokingly recalls. "We thought it was time to become rich overnight," he says.

"Finally some big studio showed interest in our project. We were ambitious to make the film a huge hit not only in domestic market, but in international theaters."

Wang says his team was like a sponge, absorbing and learning everything it could from the established studio.

Because of cultural differences and excessive inputs in its international distribution, Big Shot's overseas profit was "very frustrating".

However, Wang says the experience gained from working with a top-flight international team was very rewarding and carried over to future film productions.

Developing an eye for budget details was a good example.

Huayi's budget schedule, which was more accurate than most local companies at that time, was accurate to about 10,000 yuan ($1,400), but Columbia's budgets were calculated down to the exact cent.

Huayi needed only one page to list all the items, while Columbia had 10 pages for every department's budget, and every department had an accountant. There were more than 2,000 items on the production list.

Huayi chose only 300 of the 2,000 and Wang jokingly told Columbia his company had no money to hire so many accountants. Now Huayi's film budgets include the same cent-accurate detail.

Thanks to more and more international co-productions, many Chinese film companies are adopting the same detailed bookkeeping methods, Wang says.

Although a pioneer in international co-production among private film companies, Huayi still directs most of its attention to the local market.

"It took America about 100 years to promote its culture so that Hollywood films sell in every corner of the globe," Wang says.

"Transformers could not have earned 300 million yuan in China without the TV cartoon, which was extremely popular here two decades ago.

"When Chinese culture has not that big an influence in global cinema, to make the local cake big is still the most important thing."

DVD piracy is still the biggest problem facing the local market, he says.

Huayi's last work, Feng's war epic The Assembly topped last year's mainland box office with 260 million yuan ($37 million), but income from DVDs was zero.

Huayi would not sell the DVD copyright to disc producers because they would only accept a 15-day delay of the theatrical release, otherwise pirated DVDs would hit the market.

But Huayi insisted on 45 days to ensure the box office, so the negotiation broke up.

As for anti-piracy efforts, Wang is confident in the government's efforts.

Huayi also has plans to open its own theaters and float its company on the stock exchange.

Wang says the company is pending the government's approval to be listed in the stock market later this year. And he is to see five to 10 Huayi theaters built in major cities by the end of 2008.

(China Daily 05/13/2008 page19)