Location, location, location

|

A scene from The Forbidden Kingdom, starring Jackie Chan and Michael Angarano. File photos |

On their very first day of shooting, driving to the Gobi Desert at 4:30 am to arrive at dawn, the vehicles sank into the sand. Fifty vehicles were stuck in the dark. The crew climbed out and began collecting small stones. Without a word of complaint, and working in sub-zero temperatures, the crew collected rocks and stones for two hours until a road had been built.

"I cannot think of a crew from anywhere else who would have accomplished this," says Roger Spottiswoode, former Bond film director, who works with ChowYun-fat and Michelle Yeoh to present The Children of Huangshi (Huangshi De Haizi), a tale of a British philanthropist's adventure in 1940s China.

The spotlight is again on China, with international studios rushing in to grab a piece of the lucrative movie pie.

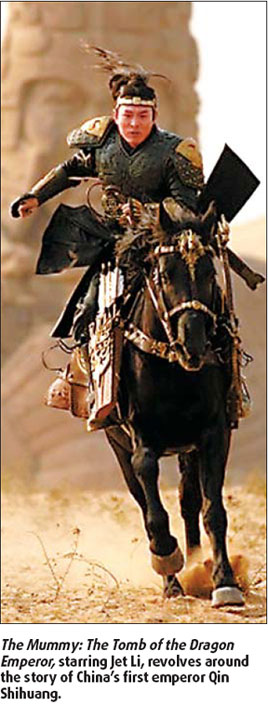

Starring Jackie Chan and Jet Li, The Forbidden Kingdom (Gongfu Zhi Wang), directed by Rob Minkoff of Lion King and Stuart Little, held its world premiere in China on April 16; Universal's $160 million sequel The Mummy: The Tomb of the Dragon Emperor, starring Li, revolves around the story of China's first emperor Qin ShihuangChina, with its 5,000-year history, has never lacked a good story. As early as 1986, Bernardo Bertolucci knocked at the gates of the Forbidden City to shoot The Last Emperor. In 2007, Disney made its first co-production with China The Secret of the Magic Gourd (Baohulu De Mimi) based on a Chinese fairy tale. Minkoff's The Forbidden Kingdom is a fusion of Chinese mythology and martial arts fiction.

China itself is a good story, with its rapid economic growth and the approaching Olympics. The world is interested in China, Spottiswoode tells China Daily. "A China-related story tends to grab attention."

The story of China is popular in Western countries, he says. "It is very difficult not to read something about China when one picks up the newspaper."

But as important as a good story is, it is money that really matters in this industry.

China's box office takings reached 3.3 billion yuan ($471 million) in 2007, 600 million ($86 million) more than the previous year. It is expected to more than double by 2010. Over the past five years, the national box office has been growing more than 20 percent every year.

"China's middle class is now 250 million," Mummy director Rob Cohen told Variety earlier this year. "We're feeling the buying power of those 250 million people."

In sharp contrast to these rich earnings is the low cost of filming in China. As is widely known, China has a variety of scenic locations and relatively cheap labor.

Beijing was one of the filming locations for Kill Bill. Quentin Tarantino was to cooperate with Japan's Toho Films at first, but the quoted price was enough to shoot just one quarter of the film. It turned out that in China, they would have to spend much less.

Terence Chang, producer of Asian action maestro John Woo's Red Cliff (Chi Bi), said in an interview to Variety that the film would have cost at least $200 million to shoot in the US. China's filmmaking costs are about a third of those in the US.

Kill Bill is considered a turning point in international productions in China, according to Zhang Jinzhan, the first assistant director and leader of the project's Chinese team.

"The Last Emperor had only a few Chinese staff, but two-thirds of Kill Bill's team was Chinese. Almost every position had Chinese and American staff," Zhang recalls. "Quentin praised China after his return to the US, and more and more projects began to move here."

What these outsiders bring to the locations is obvious. The crew of The Painted Veil transformed a local inn in Huangyao of Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region into a four-star hotel. When director Spottiswoode and Chow Yun-fat showed up on the stage of a stadium in Huangshi, a small city in central China, to announce their film's premiere, the locals saw the chance to make their city and the beautiful landscape more widely known to not only filmgoers but also to businessmen.

But international filmmakers do face challenges in China. Largely owing to the absence of a rating system, producers have to submit their scripts in Chinese to the film bureau, and sometimes changes have to be made.

Then there are the cultural issues. Minkoff tells China Daily that crews from the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and the United States need to learn how to communicate, and this can pose great difficulties.

"The production designer comes from America, but the art director is Chinese, and art designers come from different places," he says. "They have different backgrounds and are schooled in different techniques; we need to make a lot of adjustments in a short time."

Zhang Jinzhan recalls that there were two separate canteens for Chinese and international staff when they shot Kill Bill. It was not until Quentin took the lead to eat in the Chinese staff's canteen that there was more effective communication.

Zhang participated in eight more international productions later, including The Kite Runner. What impressed him most was the different working styles in Hollywood and China.

"They have a very clear schedule. The time to arrive and time to take a break is clearly defined," he says. "The crew will take at least one day break each week. This is almost impossible in Chinese productions. We don't stop until the day ends, struggling every minute to finish quickly."

Zhang says professionalism is the most important thing he has learned from his international team.

He recalls the instance when they needed to move some big boxes to another shooting location. Seeing that the foreign staff in charge of the props was a lady, Zhang gave a shout to all the crew, just like he always did when shooting Chinese films. In a second, four to five young men, from various departments, rushed to the boxes and moved them rapidly. But the next day the lady came to him, firmly telling him not to interfere in her business. Zhang felt confused, but the producer told him, she was a professional. "Although you meant to help, the guys were not professionals. Let everybody do his own job," he says.

Despite differences, Spottiswoode says he had a good time cooperating with his Chinese crew, who were diligent and devoted to work. "I think there is always so much to learn from another country and particularly from China where there is a tradition of fascinating films. The last few years, in particular, have shown us filmmakers who have a wonderful vision and eye," he says. "Chinese crews seem to be indomitable and however difficult the circumstances, they never balk."

The communication gap has given rise to a group of Chinese filmmakers familiar with both Western and Chinese filmmaking styles. Zhang Jinzhan admits that the entry of international studios and talents will have impact on the local industry, but he sees more opportunities than crises.

"Co-productions are the best chance for young talents to learn new techniques, use sophisticated equipment and think of a global market," Zhang says. "By cooperation, more and more Chinese filmmakers will be acknowledged by international studios, just as in the case of choreographer Yuen Woo-ping and cinematographer Peter Pau, who play significant roles in The Forbidden Kingdom."

(China Daily 04/29/2008 page18)