Remembering a literary colossus

|

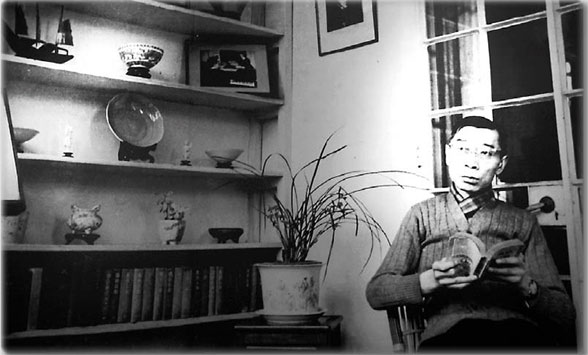

Fou Lei in his study in Shanghai, where he translated many Western classics. |

The usually quiet and spacious hall of the National Library of China in Beijing is full of people. Fou Min, son of renowned translator Fou Lei (1908-66), greets colleagues, classmates, friends and other honored guests to the exhibition marking his father's 100th birthday.

A man wearing black-rimmed glasses approaches him, introducing himself as Li Yao. "I was looking for you," Fou says, leading the way to an enlarged photo on the wall.

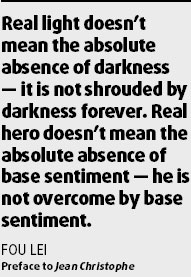

It is the front cover and title page of Jean Christophe, a work on the heroic life of a Beethoven-like musician written by French writer, Nobel winner Romain Rolland (1866-1944), and translated by Fou Lei.

Li's voice trembles a little as he recalls that autumn day in 1976 when he discovered this precious book in a Shanghai basement. Li was collecting books that the State Administration of Cultural Heritage had granted the Cultural Bureau of Wulanchabu Banner, Inner Mongolia autonomous region, where he worked.

Among the yellowing books, Li discovered the first volume of Jean Christophe, his most beloved novel. In the early 1960s, as an English student in a university, he had treasured both the Chinese and English translations of the novel.

The title page had the following eight words hand-written by a writing brush: "treasured by the translator himself, 1950". Recognizing it as a copy saved by Fou Lei himself, Li brought the book home, reading it over and over late at night, in secret.

The book was filled with corrections in red ink. From 1936, it took Fou three years to translate the book. But the meticulous scholar was always looking for a better rendition. In 1952, he worked on the book again and burned most copies of the first version.

During the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), Li had harbored a dream of becoming a translator. The book's discovery signaled that it was finally time to follow Fou's path, Li says.

When he tried to return the book, Li was astonished to hear of Fou and his wife's tragic death in 1966. Nevertheless, he went to great lengths to return the book to Fou Min, who invited him to the exhibition that opened last Monday.

Except for teaching and some other brief jobs, Fou didn't win any titles that could have secured his family a comfortable life. Yet more than 40 years after his death, numerous people continue to gain inspiration from his works that span literature, music, art and philosophy.

"Fou Lei is one of our nation's most outstanding intellectuals. He is an evergreen tree for translators and contributed greatly to cultural exchange between China and the rest of the world," Vice Cultural Minister Zhou Heping said at the opening ceremony of the exhibition, which was graced by Liu Yandong, member of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, Cultural Minister Cai Wu, Vice Chairman of the Chinese Writers' Association Chen Jiangong and other honored guests.

Fou was one of the intellectuals who grew up assimilating the cream of both traditional Chinese and Western culture in the early 20th century. He was witness to the dramatic transformations of the modern world, and always concerned himself with the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, says Ren Jiyu, honorary president of the National Library of China.

"I am relieved that the time when intellectuals were punished for saying the truth is gone forever," Ren says. The National Library has kept the manuscripts of Jean Christophe and Cousin Bons donated by Fou in the 1950s. Its collection of Fou's books is an important part of the exhibition.

For Professor Xu Jun of Nanjing University, Fou is more than a great translator, an accomplished man of letters, a sharp critic of current affairs and a person steeped in traditional Chinese culture.

Fou carried on a cause championed by Yan Fu (1854-1921) and Liang Qichao (1873-1929) who took up translation as a means of enlightening a people locked in a secluded, decaying feudal society, Xu says.

In the 1930s, when the country was shrouded in darkness as Japan invaded China, Fou translated Romain Rolland's works "to call on the spirit of great courage and bring light to the nation", Xu says.

In the 1940s, Fou embarked on an immense project to translate the works of Honor de Balzac (1799-1850). By 1966, he had done 15 of Balzac's novels in addition to 18 other Western classics.

"Fou Lei is the best reference as a Chinese translator for Balzac's works," says Christine Cornet, cultural attach with the French Embassy in Beijing, which has collected all of Fou's translations of Balzac, Romain Rolland and other French writers.

As more Chinese strive to learn English and other foreign tongues, Xu calls on people to root themselves in Chinese culture while being exposed to foreign cultures.

"The novel (Jean Christophe) influenced me greatly with its deep understanding of life. Fou Lei struck me with his noble character, he was such an upright person," says Li Yao, who has translated more than 40 works on literature, culture and history from Britain, the United States and Australia.

The free exhibition at the National Library of China runs until April 22 in Beijing, before moving to Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou and Dalian.

(China Daily 04/15/2008 page20)