Brush with fame

|

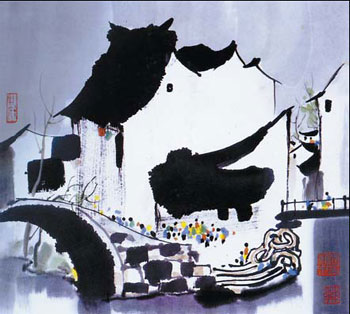

Zhouzhuang Village, ink-and-color, 1985. |

Wu Guanzhong, 89, is a living legend on the Chinese art scene. When the veteran artist speaks, people listen; when his paintings are auctioned, people rush to buy.

The Jiangsu-born painter, who some say has transformed modern Chinese art, has once again become a focus of attention over the past weeks.

Early this month, artron.net, a leading art website in China, ranked Wu high on its Artists of the Year list in recognition of the high prices that his paintings have fetched as well as his controversial remarks concerning Chinese art circles.

Wu also tops the newly released 2008 Hurun Contemporary Art List for his record-setting sales figures of more than 370 million yuan ($52 million).

At the 2007 Poly Spring Auction last May alone, Wu's colored ink painting Ruins of Jiaohe fetched over 40.7 million yuan ($5.7 million), the highest figure paid at auction for a piece by a mainland artist.

The opening of Wu's latest solo art exhibition at the 798 Art Zone, which usually displays contemporary Chinese art by young artists, drew a large number of fans.

And jaws dropped when the 89-year-old said: "Coming to the 798 Art Zone is like coming home."

"I am 89 years old. But that does not mean I am too old to learn and try new tricks," Wu said to a packed house of fans and journalists.

Indeed, the 50-plus paintings on show stunned many attending the exhibition.

"On first seeing these dynamic yet poetic paintings, you would never imagine they are from the hands of a painter of that age," says Jia Fangzhou, the curator of the exhibition.

Others have tried to learn whatever they can from Wu's works.

"My teacher has always been a role model for me as a devoted and innovative artist," says Li Zhengming, a former student of Wu's who has seen the master create some of his best-selling paintings.

Born in Yixing, Jiangsu province, in 1919, Wu, at 17, enrolled at the National Arts Academy of Hangzhou, studying both Chinese and Western painting under the guidance of Pan Tianshou (1897-1971) and Lin Fengmian (1900-1991).

In 1947, Wu traveled to Paris to study at the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux Arts, on a government scholarship.

He admired Utrillo, Braque, Matisse, Gauguin, Cezanne, Picasso and especially Van Gogh.

Three years later, upon the founding of New China, Wu returned to Beijing and became an art educator.

However, as Wu reached his artistic peak in his 40s, the "cultural revolution (1966-76)" erupted.

Wu was forbidden from all artistic creation until 1972; at 53, he was allowed to paint one day a week.

He then did a dozen famous oil paintings depicting rural life, while he was farming in North China's Hebei province, using paperboard instead of canvas, and a manure basket as his table.

When Wu returned to Beijing in 1973, he discovered his courtyard room was too small for oil painting.

This inspired the artist to develop a new method of ink-and-wash painting.

"Wu has always been ready to challenge conventional ideas and is respected by many for his constant search for artistic expressions that best suits his inner feelings," Li says.

An eclectic artist who has tried to merge ideas from East and West, Wu has created a body of work that is appreciated by both Chinese and Europeans.

Wu says that this cross-cultural fascination was sparked by his mixed educational background.

"Elements of Chinese and Western art are bound to clash in my mind," Wu says.

For many, Chinese and Western paintings are diametrically opposed to each other. However, Wu sees it differently.

"It's like climbing a mountain from different sides. Landscapes on the two sides may look different at the foot of the mountain, just like the scenes on the Nepalese and Chinese sides at the foot of Mount Qomolangma," he says.

"But the higher the mountaineers go up, the more similar the scenery becomes. The mountain-scape becomes exactly the same when the two climbers finally get to the top."

In fact, Wu argues that Chinese and Western arts communicate with each other. What make them feel different are the superficial mediums such as ink, rice paper, oil paint and canvas.

|

Glamour, ink-and-color, 2007. |

However, Wu's approach of "capturing the beauty from the outset", his advocacy of formal beauty and his remark - "brush and ink equal zero" - ignited a fierce debate among Chinese ink painting circles in the 1990s.

Some critics even called Wu a traitor of Chinese painting traditions, while others said that Wu did not really grasp the gist of Chinese ink art.

"What I have been doing is digging up the essence of beauty in Chinese painting, which is hidden from most Westerners by Chinese brush strokes and the Chinese way of coloring, and I have tried to present it to people other than Chinese or Asians in a way that they understand," Wu says.

In Wu's view, anatomical analysis, perspective and three-dimensional expression in paintings constitute the very basis of Western art, allowing it to depict faithfully the texture, size, color, and shape.

Modern Western art, however, discards unnecessary details and concentrates on capturing the underlying beauty, mood and emotions.

In contrast, traditional Chinese painting has not gone through the baptism of systematic techniques and formal expression, Wu says.

So, its forms of expression are rather limited.

"I wanted to use the Western artistic scalpel and microscope to sum up, enrich and push forward Chinese painting traditions. Of course, I also wanted useful elements in Chinese art to remain instrumental in my painting," Wu says.

In 2007, Wu again sparked a public debate when he openly criticized the rigidity and bureaucracy of the official Chinese Artists Association and the Chinese Ink Painting Academy system.

"We all know that poets do not trade their poems for money; like poets, artists should support themselves, instead of relying on salaries from the government," Wu says, suggesting that the official institutes for Chinese art should be disbanded and all the artists should find their place in the art market.

However, when asked whether he cares about the astronomical prices that his paintings fetch at auctions, Wu replies with a smile: "No. I understand there are speculations in the art market; I am not sure whether the auction prices indicate the real value of paintings. But one thing is for sure: I believe paintings that can withstand the test of time are real masterpieces."

At 89, Wu still paints almost every day, while the rest of life is relatively simple.

"I do not raise a cat, dog or plant flowers. Nor do I indulge in music. Painting is my lifetime hobby and the pillar of my soul," Wu says.

(China Daily 03/11/2008 page19)