Women and science do mix - and mix well

Why does a rainbow appear after rains? Why does a small stone thrown into a river cause ripples? Why does a person's body lean forward when a car's brakes are applied suddenly?

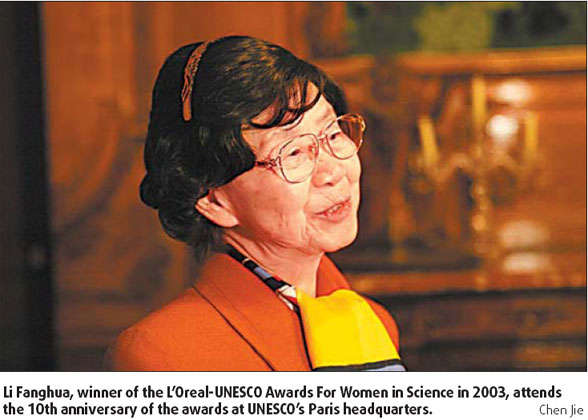

These were the kind of questions that fascinated Li Fanghua as a young girl. Winner of the L'Oreal-UNESCO Awards For Women in Science in 2003, Li recalls that it was this fascination with everyday phenomena that led her to pursue the study of physics.

This week, Li, whose discovery of novel techniques in electron microscopy made her the first Chinese person to win the so-called "women's Nobel Prize," met with other laureates to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the awards at UNESCO's Paris headquarters, to share the trials and triumphs in their careers and lives.

Decided by an 18-member international jury, presided over by Gunter Blobel, winner of the Nobel in Medicine in 1999, this year's awards go to five women researchers in the life sciences. The awarding ceremony was held Thursday evening (Paris time).

The L'Oreal-UNESCO Awards For Women in Science is the first international award devoted to women scientists. "It is aimed at recognizing the contributions of outstanding women researchers to scientific progress and encouraging the participation of women in scientific research," says Koichiro Matsuura, director-general of UNESCO.

"Ten years and 52 laureates from 26 countries, there is no doubt that this award is fulfilling its promise," says Beatrice Dautresme, vice-president of L'Oreal and one of the founders of the program. "The laureates serve as role models for future generations, encouraging young women around the world to follow in their footsteps."

Fumiko Yonezawa, Japanese professor Emeritus of Physics, Keio University, agrees.

"Girls often struggle to find examples of female scientists to whom they can relate. If you want to be a female singer, there are success stories all around you. However, female researchers' achievements are rarely seen other than in specialist publications," says Yonezawa, a 2005 winner.

Hong Kong neurobiologist Nancy Ip and one of the 18 jury members, gives her own example. More female students applied to study with her after she won the award in 2004, she says. Two of her students from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology went with her to the celebration in Paris to gain some international exposure and network with women in science.

But the overall picture of women involved in science and technology remains challenging.

The UNESCO report shows that female participation in higher education has increased in the past 10 years in most regions of the world. However, once they have finished their studies, only 25 percent of researchers in science and technology are women; 75 percent are men.

China is no exception. At the university level, gender parity is much better than at the research level. Percentage wise, there are more women science students than researchers. After their studies, however, women change direction. Moreover, even when women do manage to enter science or engineering, they often drop out early in their careers.

Based on questionnaires and interviews with 2,971 female scientists and engineers nationwide and graduate students in Beijing, a CAS report released last year shows that 94 percent of female respondents experienced discrimination when trying to find a job.

Among them, 43 percent said "the employer prefers male researchers", 24 percent said "some employers directly say no to women", 17 percent said there was an "additional requirement for women employees" and 9 percent ticked yes for "senior positions for men, while low positions for women."

"The higher you look in the scientific hierarchy, the lower the percentage of women. Research is traditionally a male-dominated area and there is still a long way to go before there is parity," says Li, who became a member of Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in 1993.

Besides discrimination, research work makes it hard for women scientists to accommodate family life. While trying their best to balance work and family life, women professionals have to bear the major responsibility at home, which does influence their career development.

According to the CAS report, only 12 percent of men do the housework and take care of children, while the corresponding figure for women is 78 percent.

"Women in S&T research need the support of the family - the husband and kids," Li says.

"My husband shares the household chores with me. Usually he does the heavy work while I take care of the lighter work," she says.

But she is quick to add that women should not demand too much sacrifice from their husbands. "Whenever I take a female student, I tell her first, 'balance your work and family life and never ask your husband to do more housework'."

Li is a model wife and a model mother to her son and daughter. She cooks, washes, sews and can even make her own clothes. She enjoys cutting and sewing and once told her daughter, "If I was not a scientist, I could have been a good tailor."

(China Daily 03/07/2008 page18)