Back to nature

An Jinlei removes the earth with a pickaxe to reveal plastic sheets left from last year. He picks them up and stashes them in a big bag. Most farmers don't take so much trouble. They simply drive through the fields with tractors when spring comes and the plastic is buried deep underground.

|

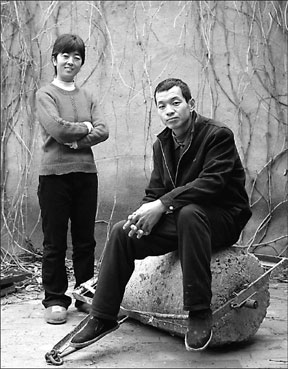

An Jinlei and his wife Zhang Xiushuang lead a simple, but admirable life. |

"In 10 years, a 1-cm layer of plastic will accumulate in the earth. How can you plant anything then?" An asks.

An and his wife are different from their neighbors in Dongzilong village, Zaoqiang county, about 130 km to the southeast of Shijiazhuang, capital city of Hebei province.

Since 2005, they have reserved a field for sparrows, swallows, magpies and dozens of other wild bird species. When the vast fields of the northern plains are empty through winter, tens of thousands of birds hover above An's fields.

"The county's sparrows are having a meeting," An once told his wife.

Instead of using pesticides or chemical fertilizers, the couple makes their own organic fertilizer with manure and weeds. They plant various crops in small patches of their fields and allow weeds to grow on the fields at least three months of the year.

An says: "When pesticides are used on a field, grass doesn't grow, insects don't grow. The earth is silent like death. Only crops grow. Can humans destroy other lives for their own interests?"

Most young people in the village earn extra cash through working at construction sites in the cities. But An never leaves his fields, except for brief trips to consult agricultural experts, or other farmers.

The farmer, in his mid-30s, says if he gets tired, he just takes a nap in the field, "while the earthworms loosen the soil and birds eat the insects".

Though villagers laugh at the couple, they love eating An's watermelons and envy his cotton, which has the highest yield and best quality.

|

An fondles a white turnip grown at his fields. |

Before An graduated from an agricultural vocational school, he hadn't worked in the fields before. His first job at a State-owned farm was to get rid of grass in the watermelon fields.

"It was repellent. I opened the first bottle of herbicide and couldn't stand it," An recalls. "The earth must feel terrible, the plants must feel terrible. Everyone calls the Earth Mother. Isn't spraying herbicides the same as poisoning your own mother?"

An sought help with experts from the China Agricultural University and Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Professors said organic farming was still theoretical and a single farmer couldn't accomplish it, or make ends meet.

But An wouldn't give up. He began testing his own manure made of chicken and sheep droppings. When he left the farm and returned to the village in 1997, An was ready to expand his experiment.

There was a patchwork of fields covering 26,000 sq m far away from the village, left uncultivated for years. An got the land by contract for 2,000 yuan ($280). Everyone thought he was mad - except his wife Zhang Xiushuang.

Zhang came from another village. She turned down the proposal of a man in Shijiazhuang - the promise of comfortable urban life - and chose An because she wanted to be with someone who has "read books".

The couple often read books in their fields when they take a break. An favors poems from the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), while Zhang reads those by contemporary poet Wang Guozhen, who was popular in the early 1980s.

|

An heads to his fields. Photos by Yu Chuzhong |

One dry autumn, some 2,000 swallows gathered on the muddy pools near their fields to drink and bathe. An says the birds knew the water was clean and safe.

The couple has also found that earthworms are great at scarifying the soil. Some insects like to eat weeds. Surrounding the cotton fields, the corns entice moths, while sesame drives cotton aphids away.

For three years since 2004, cotton production in northern China suffered heavily from plague and drought. An's cotton field attracted national attention as the plants grew over 1.5 m tall and kept on blossoming, producing a surprising yield of 200 kg per mu (666 sq m). An underwear company has signed a contract with the farmer to buy all his cotton at 9 yuan ($1.30) per kg, about 4 yuan ($0.60) higher than the average price.

An was happy to share his cottonseeds with neighbors. But none of them has been able to reach the same high yield. As An explains, most villagers consider his farming methods too time consuming.

When he was a child, An envied his urban classmates, because their exercises books had squared paper, while he had to draw lines by himself. Now, the city is synonymous to him with a horrible life.

"An urbanite cannot be connected with the earth, bathe in the sun and rain, or breathe fresh air. He has to endure the rumbling of machines and stuffy cement houses.

"The city is not a place for humans to stay. It is anti-nature. It is a tumor."

At his three-roomed, tiled flat in a dusty alley, the couple lives a simple Buddhist life. They use little seasoning while cooking their homemade vegetables and use branches of cotton and corn as firewood.

After dinner, An rubs the bowls and chopsticks with wheat bran, which becomes supper for his two dogs. The dogs have shiny, smooth fur, though they also live on a vegetarian diet. On the roof, shallow containers store rain for the birds.

The couple has an old TV that has eight channels. But they prefer the radio. When they got married in the early 1990s, they loved sitting in the shade, listening to agricultural programs from the village's loudspeaker. However, the radio is not as satisfying for them as before.

"(Today) the most programs tell you how to get rich quickly," Zhang says.

On busy days, An lives in an earthen cottage near the fields. He often sits in the open air with his wife, looking at the starry sky.

With a friend's help, the couple has sent their 12-year-old son to the Waldorf School in Chengdu, Southwest China's Sichuan province. The school practices Waldorf Education, championed by German philosopher Rudolf Steiner in the 1920s. Students at Waldorf enjoy great freedom to play and work in farm fields.

An doesn't worry that he hasn't saved enough for his son. "It is impossible to support him through higher education with the income from the farm. Let him return to the fields if necessary."

Sanlian Life Weekly contributed to the story

(China Daily 03/05/2008 page20)