Schooling begins at home

|

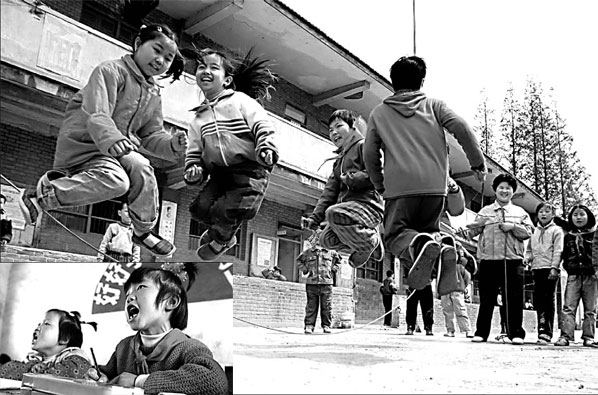

Students of a Hope Project school in Nantong, Jiangsu province at work (inset) and play. Photos by Ding Xiaochun |

On a hot summer's day in August 2006, Lamao Cering crouches in a windy field in Qinghai province repeating "I want to go to school" like a mantra, oblivious to her father's call to come back and tend the sheep.

Seven years earlier, the 17-year-old Tibetan girl from impoverished Langjia village in West China was attending school like any other child. Then, she was forced to drop out, against her will.

Lamao Cering is just one of many children in rural China who have quit school to work instead. Parents with little education themselves often do not see the benefits of education for their children.

These parents see the benefits of leaving school early as two-fold: School fees can be saved and the children can contribute income to the family.

For Lamao Cering, her situation has worsened over time. She is too old to attend basic classes and lacks the credits needed to attend college.

A recent survey by UNICEF reveals that many people from ethnic minorities are stuck in a similar situation due to poverty, poor school quality issues and the migration of families to urban areas.

Niu Lingjing, project director with the China Association for Science and Technology (CAST), says young people like Lamao Cering were a special group in society, stuck between childhood and adulthood.

"They have little or no guidance on how to improve their quality of life and how to protect themselves in vulnerable situations," Niu says.

In order to help such adolescents CAST, along with UNICEF, has developed a non-formal education project for out-of-school children to address their learning and developmental needs.

The non-traditional educational project started in 2006 and is set to continue to 2010. It will provide life educational skills and science literacy for out-of-school rural children aged between 10 and 18.

Since joining the project a year ago Lamao Cering has learned embroidery and how to tend her family's flock of sheep, so they can grow healthier and stronger.

During a visit to Lamao Cering's home, the project teacher receives a warm welcome from the family.

"Come and take a picture with me", she beckons to her teacher, inviting her to stay the night in the small but tidy home.

"I'm completely astonished at the change in her," says Zhang Xiaolei, a project manager with the Qinghai Provincial Association for Science and Technology. "When she first attended she barely spoke. I was even thinking that maybe she didn't speak Mandarin at all."

On her first day at the Learning Center in her village Langjia, Lamao Cering remembers that she sat at the back of the classroom, completely indifferent to what the project workers were saying.

"I was very nervous back then and doubtful if it could do anything for me. I wanted to go to school and the center makes me feel like I am. "

Thanks to the project, Knowledge Information Resources Centers (KIRCs) have been established, which cater for more than 3,000 out-of-school children, in 20 counties and 10 provinces last year.

Life skills-based education is being adopted as a means of empowering young people. At the KIRCs the children learn life skills, computer skills, and through arts and sports activities, leadership, team building, self-expression and confidence are developed. They also learn about health and hygiene, science and the law.

Nyi'ma Cering is an 18-year-old from the Tu minority. He is a devout Buddhist from Qinghai's Nianduhu village who spends his time making thangka, Tibetan Buddhist scroll paintings. He is also a member of the regional art association and has started to teach his skills to other children.

When not painting, he likes going to the KIRC and organizing activities. After two years, he is taking on the role of mentor at the KIRC and is responsible for running a local KIRC chapter in their village. He also went to Xining, capital city of Qinghai, to participate in the provincial sports games and helped out with a summer camp in Beijing for out-of-school children.

Nyi'ma Cering's father Legba says: "At first, we were very doubtful about the project but allowed him to try it. Then we realized he was energized by the experience and even learned to tend the sheep better."

It is evident that the project is paying dividends. At Tongren, an impoverished county in Qinghai, four youngsters who participated in the project have left to work in other provinces, in jobs with better salaries and working conditions.

With the knowledge they have gained at the center, they now know more about protecting themselves from HIV/AIDS and other diseases, and they're more confident, says Doje Cering, deputy head of Tongren County.

Despite the positive results, some of the pilot schemes have been cut due to language and travel logistics problems.

"We hope more people will focus on this special group of children and help them receive further education and realize their dreams," CAST project manager Jiang Jingyi says.

To help these kids attend school, a national four-year plan promoting education was launched in 2004 focusing on abolishing tuition fees. In addition, more college graduates are becoming teachers and boarding schools are being built for students whose homes are a long way from school.

"In poor western counties, tough conditions can limit local educational resources and the cost of promoting compulsory education is much higher than in other areas," says Tian Zuyin, a senior official with the Ministry of Education.

According to the Ministry of Education, nine year of compulsory education, including six years at elementary school and three years at junior high school, was expected to be the norm for 98 percent of children in the poorest areas by the end of last year.

The project is expected to develop a sustainable and replicable model of non-formal education in rural areas for children and improve the equality and quality of education, says Zahirul Karim, section chief of education and the child development program, UNICEF China.

(China Daily 01/31/2008 page20)