Reviews

Books Anonymity by John Mullan, Faber

Today, in virtually any Waterstone's, Smiths or Borders, the UK's main bookshop chains, the piles of Nigella Lawsons, McEwans, Clarksons and Russell Brands seem to demonstrate one simple equation: books equal celebrity. Actually, as John Mullan (pictured) shows in this provocative little volume, writers used to go to extraordinary lengths to remain anonymous.

With good reason, books were a matter of life and death. For the first three centuries after the introduction of the printing press, writers who challenged religious or political orthodoxy (and what is the use of a book that does not risk a contrary opinion?) were in mortal danger. Translations of the Bible, especially, offered a short route to immortality. Tyndale was burned at the stake. Lower down the slopes of Parnassus, even so fine a poet as Shakespeare published anonymously, after first circulating his work in private. Anon remains the star contributor to most dictionaries of quotations.

Printers often paid with their lives. Where the many were at odds with the few, words were weapons. In 1663, after the Restoration, the anonymous author of a pamphlet arguing the people's right to rebellion escaped the king's justice, but his printer was hanged, drawn and quartered.

Anonymity, before the Age of Reason, was a matter of common prudence, but publication could still get a writer into trouble. In 1679, John Dryden, England's greatest living poet, was so badly beaten up by a bunch of thugs for the supposed authorship of an anonymous satire that attacked one of the king's mistresses that his life was reported to be "in no small danger".

Perhaps it was the marketplace that blunted literature's keenest edge. After the Civil War, many new books, especially novels, became entertainment for middle-class readers. Any offence they might give was now confined to the library or the drawing-room. Where anonymity once protected an author's life, now it was an expression of his, or her, modesty.

Today, the surest kind of anonymity is failure, neglect and rejection. Take deliberate refuge in anonymity and you will probably ignite a firestorm of publicity. American political columnist Joe Klein published Primary Colors, his account of the US election process as "Anonymous". The reviews and the sales were great, but the American press could not make its peace with the author until Klein had been exposed and humiliated.

In the high-speed age of short attention spans and competing media, the author's presence provides an essential short cut to the reader's grasp of the text. In this instance, Professor Mullan has produced a thought-provoking volume, full of good examples and research. Did he never think of publishing it anonymously? The Guardian

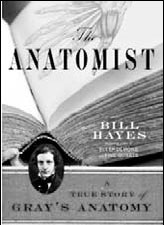

The Anatomist: A True Story of Gray's Anatomy, by Bill Hayes, Ballantine Books

How do you write a book about someone about whom next to nothing is known? For most writers, the answer would be move on to the next subject. But Bill Hayes has an unusual set of skills. The author of previous books on insomnia and blood, he is part science writer, part memoirist, part culture explainer. The Anatomist, his appealing new book about the man behind Gray's Anatomy, combines his search for the remaining traces of Henry Gray with a memoir of his own experience as a dissection student and a scalpel's-eye tour of the body. Hayes soon finds that the man who defined the known contours of the generic human body is impossible to pin down. He left no diary, no letters, few case notes. Was he born in Windsor or London? No one knows. After his death from smallpox, at age 34, his possessions were most likely burned. He left behind a single work, more than 1,000 pages of precise descriptions of parts of the body most of us still don't know exist. The New York Times Syndicate

(China Daily 01/23/2008 page20)