Children of the revolution

|

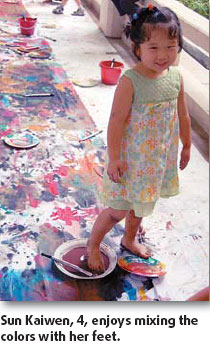

Art Children workshop offers children free-choice, hands-on, explore-on-your-own activities. Photos courtesy of Art Children |

One night around two years ago, Yang Jiechun sat with her husband and mother-in-law trying to solve a family dispute regarding the education of her daughter, Xing Yutong, who was then aged 4.

It was Yang's idea to send the girl to Art Children, a workshop for pre-school children run by Hu Xiaopei, an art education expert. Unlike traditional Chinese art workshops which favor structure and discipline, Art Children offers free-choice, hands-on, explore-on-your-own activities.

Initially, when Yang proposed the idea, there was a consensus within the family. Like most parents and grandparents in China, the Xing family believes that art education stimulates creativity, one of the most valuable assets in today's competitive world.

Xing's grandmother had happily taken the responsibility to escort her granddaughter on her weekly visit to the workshop. Three weeks later, however, she changed her mind. In her opinion, the workshop was nothing more than "an expensive playhouse," where "the teacher was allowing her to scrawl whatever she wants." She insisted it wasn't worth the money, which for 50 visits lasting 90 minutes each, cost the family 6,750 yuan ($928), approximately three months' salary for a working-class family in Beijing.

Yang doesn't agree. Even though she didn't receive much art education in her upbringing, after a few lectures by Hu, Yang was convinced of the importance of free play for pre-school children.

"Art education can't be hurried," Yang says. "Otherwise, she will lose her feelings for pure, simple things.

"It has been the tradition for Chinese art education for generations - to follow the teachers' instructions, and that really discourages creativity and imagination."

Even Hu, a children's art education expert, admits that she trod a hard way to discover the path to creativity.

In 1997, Hu, an art history graduate from China Central Academy of Fine Arts, was a successful art curator. She was in Germany on an exchange program when someone proposed the idea of holding a joint exhibition of children's art works.

Fascinated by the idea, Hu spent the following three years scouting for pieces. By the summer of 2000, she had accumulated more than 100 paintings by children all over China.

However, before the exhibition opened, Hu realized that the works of the German children were much more varied than those of the Chinese children. The Chinese pieces were superior in technique, but they were comparatively monotonous in terms of style.

Her curator partner was also confused.

"He believed me that there were more than 80 participating children, but the works seemed to be from at most 10 different ones," Hu recalls. "At one point, he was pointing to a skillful yet extremely sad portrait of an old farmer and asked if the 11-year-old boy was suffering depression.

"It was at that moment that I realized what huge problems existed in China's current art education.

At the last minute, Hu and the German curator decided to reshuffle the exhibition, deciding not to separate the works of the two countries. They also transformed the exhibition hall into a workshop where young local artists were invited to paint on spot.

The exhibition turned out to be a success. However, Hu understood that "while the problem can be blurred in one way or another, it can't be ignored."

Hu then began researching art education. In the following years, she paid numerous visits to art workshops for children in China and other countries.

|

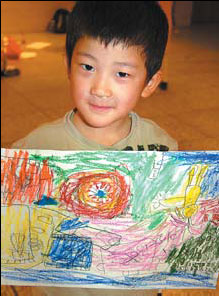

Yu Qingyang, 5, proudly shows his scrawl at Art Children. |

"In the West, art education is more student-focused. In an art workshop for children, children have the final say. While in China, children are usually put in a position to obey or follow," Hu says.

Through years of research, Hu became an expert in the field. In an attempt to raise public awareness about art education reform, Hu has published many articles in various newspapers, magazines and online forums. She also gives lectures to parents and art educators from kindergartens and schools at various levels.

While more art educators have come to realize the importance of offering a more creativity-friendly environment for their students, parents have also been enthusiastic about the changes.

Li Chen, who runs a kindergarten, agrees.

"Many Chinese parents have come to realize how important it is that their child expresses their creative side," says Li.

Li started the first Wardolf kindergarten (based on the Wardolf education model) in Beijing around the same time Hu started Art Children in June 2005. While both of these businesses have proved successful, Hu says that her workshops have received mixed responses. Over the past two and a half years, Hu's workshop has received more than 600 children aged between 3 and 6, with Xing Yutong one of the current students.

At that family meeting two years ago, it was Xing's father who had the final word. "I let my daughter decide by herself," he said.

The father summoned his daughter and asked, "Are you happy with Aunt Hu from Art Children?"

The 4-year-old nodded.

"Do you want to go there again?" continued his father.

"Of course," said the girl. "I'd love to."

(China Daily 01/10/2008 page18)