Taj Mahal turns back on greenback

|

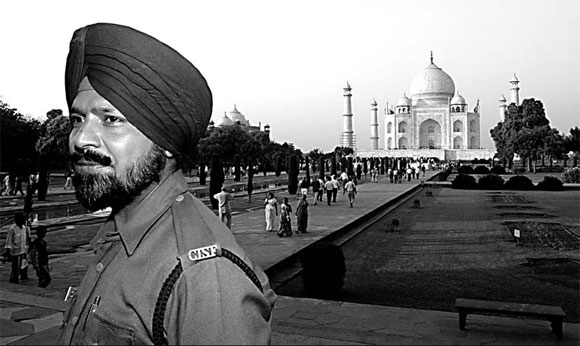

An Indian security officer stands guard outside the Taj Mahal in Agra, India. Amit Bhargava/Bloomberg News |

The Taj Mahal, one of the world's architectural masterpieces, welcomes about 2.5 million visitors each year - provided they don't try to buy tickets with dollars.

India's most popular shrine announced in November that it would stop accepting the US currency and take only rupees, hurling yet another insult at the once mighty greenback.

The dollar, which has been snubbed by everybody from government officials in Kuwait and South Korea to top-earning Brazilian supermodel Gisele Bundchen, may not recover its luster. Economists say the currency, which has declined in five of the past six years against the euro, is caught in a downdraft as investors pour into Asia, prompting a tectonic shift in economic power from the United States.

"Can it be turned around? Probably not totally," says Riordan Roett, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. "The century of Asia has arrived, and the US and its European allies will need to adjust to that."

In Asia, an investment boom has boosted local currencies. In India, the economy has grown at its fastest pace in the past four years since independence in 1947. That's helped lift the rupee 12 percent against the US currency in 2007 through Wednesday.

Dollar bulls say the currency, which rose to its highest in seven weeks against the euro on Monday, could rally further in 2008. They cite the fiscal 2007 US budget deficit, which fell to $162.8 billion compared with $412.8 billion three years earlier. And the current account deficit narrowed to $178.5 billion in the third quarter after reaching a record $217.3 billion in the 2006 period.

Rise expected

Deutsche Bank AG, the world's largest currency trader, predicts the dollar next year will rise about 2 percent more versus the euro, a currency shared by 15 nations as of January.

Longer term, the slowing US economy - hurt by a banking and consumer credit meltdown that's only getting worse - will weigh heavily on the dollar. Since August, the Federal Reserve has cut interest rates three times to 4.25 percent in December, and traders in federal funds futures see about an even chance the rate will be 3.75 percent by May.

The Fed's moves, coupled with the European Central Bank's threat in December to raise rates, have tilted the odds against the US currency. In 2007, it fell 8 percent against the euro and 2 percent versus the British pound through Wednesday.

Asian and Persian Gulf nations are concerned that the flight from the dollar is feeding on itself and may spur a crisis of confidence. Kuwait abandoned a dollar peg in May due to its weak buying power. South Korea's central bank in November urged shipbuilders to issue invoices in won, the country's currency, and take out more hedging policies to guard against the weakened dollar.

Dominance ending?

Peter Kenen, a professor of international finance at Princeton University, raises the possibility that the dollar's role as the world's dominant reserve currency may be coming to an end. The dollar's share of central banks' currency portfolios slid to 64.8 percent in the second quarter of 2007 from 71 percent in 1999, the year the euro debuted, the International Monetary Fund says.

Cash-rich governments, mostly in Asia and the Middle East, may shift as much as $1.2 trillion in dollar holdings to other currencies in the next five years, Merrill Lynch & Co economists say.

"The dollar will not recover completely its dominant role in the system, although it may well share that role with the euro and even the pound," says Kenen, a former Treasury adviser. "What some of us thought could happen in the distant future may be upon us now."

Economists debate whether the administration of President George W. Bush wants the dollar to appreciate.

After US trading partners in Europe and Japan criticized the currency's decline, US Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson in November stepped up his rhetoric about the economy's long-term growth prospects to instill confidence in the dollar, says Jens Nordvig, an economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc in New York.

With the weak dollar spurring US exports - one of the few bright spots in the economy - some economists don't take Paulson at his word.

"The Bush administration is not sincere in saying it wants a strong dollar," says Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson, a professor emeritus at MIT. "The long-run trend for the dollar is very likely to be downward."

The currency will be barred from more places than the Taj Mahal in the event Samuelson is right.

Bloomberg News

(China Daily 12/21/2007 page16)