Reviews

Exhibition Witnesses of friendship

In AD 753, the venerable Jianzhen finally landed on the shores of Japan after five failed attempts to spread Buddhism to the island country. In the last 10 years of his life, the blind master, known as Ganjin in Japan, established the Ritsu sect of Buddhism at the Toshodaiji Temple in Nara.

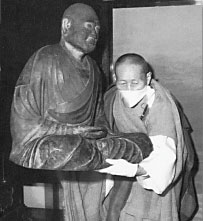

In 1980, the dry lacquer statue (pictured) made of Ganjin shortly before he died was brought back by the abbot of Toshodaiji Temple to Ganjin's hometown in Yangzhou, East China's Jiangsu Province. The short trip symbolized the centuries-old friendship between the two nations.

This year marks the 35th anniversary of the normalization of the Sino-Japanese relationship. The China International Exhibition Agency under the Ministry of Culture is presenting a photo exhibition on cultural exchanges between the two countries.

Besides the photo showing the home trip of Ganjin's statue, more than 130 other snapshots bear witness to the continuous efforts by political and cultural figures on both sides to tighten the friendship between China and Japan, since 1955. The exhibition also highlights the on-going Sino-Japanese Cultural and Sport Exchange Year. It is held at the Beijing World Art Museum of the Millennium Monument, and runs until Friday. Lin Qi

Book

Taste: The Story of Britain Through Its Food

By Kate Colquhoun

The cliche was once that Britain had woeful cooking, the worst in Europe. Foreigners wrote home with details of floury brown soups, overboiled vegetables, watery stews and coffee that, in the words of Kingsley Amis, "tasted of old coffee pots".

Why was it, people asked from 1800 until about 1980, that a country so rich in promising raw materials (beef, fish, lamb, game, cream) had the habit of murdering their flavors on the way to the table? The question was aggravated by the divisions created by social class and by the shortages of war.

By the 1960s, prosperity provided European holidays and different ideas of cooking, and waves of immigration had begun to establish Indian and Chinese restaurants, peppered with a scattering of Italian and Greek, in every British high street.

All the evidence as to why Britain developed such a poor cuisine points to the triad of the Industrial Revolution, empire and free trade. The first drove people from the fields to the factories; the colonies of the second grew what Sidney Mintz has called the tropical "drug foods" (including sugar and tea); the cheap imports encouraged by the third drove out the homegrown.

New York Times Syndicate

(China Daily 12/13/2007 page20)