The pros of poetry

|

Dr Wolfgang Kubin is helping contemporary Chinese poetry gain worldwide recognition. Erik Nilsson |

He's notorious for writing off China's contemporary novelists, but few people know German Sinologist Dr Wolfgang Kubin has wonderful words for some of the period's poets.

And the professor from the University of Bonn, who says his damning comments about Chinese writers were misquoted and overstated, believes this has gone on for too long.

"Wherever I go, I always say there are a lot of Chinese poets, maybe a dozen, who belong to world poetry," he says. "I say this, but nobody pays attention to this. They're not interested in me praising these Chinese poets, because they don't estimate contemporary Chinese poetry like they did in the past."

But many Germans do, Kubin says. The Sinologist who has translated works by nearly all of the genre's poets into German is one of the country's biggest fans, praising authors such as Bei Dao, Ouyang Jianghe, Zhai Yongming, Duo Duo, Hu Shi and Xi Chuan.

According to Kubin - known by Chinese as Gu Bing - German literature houses are particularly fond of works by contemporary Chinese poets and invite several to visit the country every year. Some of these purveyors of prose have up to six works published in Germany, and the country's academia produces a steady flow of research on the genre.

"In some respects, you could say that Germany is the home of Chinese poetry in the Age of Globalization," Kubin says. "Many (poets) aren't read by Chinese, but in the West, they have readers. There might even be more in the West than in China."

Kubin believes the genre's popularity in Germany partly owes to the good and the bad of the world's increasing interconnectivity.

"In the Age of Globalization, not a few Westerners long for a different language. The language of globalization is made up of types of English that aren't really English at all - wrong English, or nonsense English. People are longing for a more complicated language," Kubin says.

And the English-speaking world is slower than Germany to catch on to contemporary Chinese poetry. But, as Kubin explains, that might not be their fault.

"I think we still translate more poetry for the English-speaking world. But the problem is that sometimes the translations aren't published in the United States or Great Britain, but rather, in some places such as Hong Kong, or even the Chinese mainland," Kubin says.

But the professor, who has translated more than 30 volumes worth of material into book form, is reluctant to admit that his commitment is one of the main agents of the genre's success in Germany.

Since 1989, Kubin and his wife Suizi Zhang-Kubin have run the biannually published journal Minima Sinica, which features translations from several genres of Chinese literature, including dramas, essays and poems.

For his years of dedicated work, the Sinologist was given China's most prestigious literary award, the Pamir International Poetry Prize, in Beijing in October.

However, the award comes at a time, he says, when he's tiring of the "self-sacrifice" of his mission.

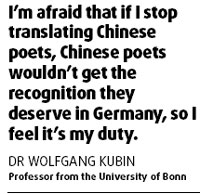

"Actually, I'd like to stop my translation work, because it's too time consuming and keeps me from doing my own creative work. But I'm afraid that if I stop translating Chinese poets, Chinese poets wouldn't get the recognition they deserve in Germany, so I feel it's my duty," Kubin told China Daily before the awards ceremony.

According to Kubin, Germany is today home to six first-class translators, but they almost exclusively work on novels and dramas.

"Poetry and essays don't sell, but novels and dramas sell," Kubin says.

Kubin was among the few Germans of his time to learn Chinese. He originally studied to become a pastor but became frustrated upon finding the university courses had little relevance to real life. He was at a loss for what to do until he came across, and immensely enjoyed, work translated from Chinese by Ezra Pound.

He had already studied several languages but had not yet tackled an Asian language. The challenge of Chinese, which at first intrigued him, later consumed him.

Because China wasn't open to foreigners in 1969, Kubin instead traveled to Japan.

"What I was looking for was medieval China; in parts of Japan, you can find medieval China," Kubin says. "The Japanese started to rebuild anything they found in China. If you want to find the architecture of the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), you can't find much of it in China anymore, but you can in Japan."

In 1972, he seized his first chance to come to the mainland, where he trained as a classical scholar.

"I wouldn't have learned contemporary Chinese if I hadn't had this chance to come to China," Kubin says.

One day in 1981, he went to Beijing Library, where a local woman helped him find books. Because he frequented the library, the two ran into each other often and, over time, developed a relationship. However, because it was then illegal for foreigners and Chinese to court or marry, they had to keep their love secret.

They finally wed in 1985, when Suizi Zhang-Kubin came to Germany as a student.

Since leaving China, Kubin has made frequent return trips to teach university courses, lecturing this year at Ocean University of Qingdao and Sichuan University.

"People want me to teach Chinese, because they're looking for new methods, and they think that through my methods, they can find a new approach to Chinese literature," he says.

The scholar, who believes 1919 - when poets began using bai hua (common language) - was a "watershed" for Chinese poetry, says that today, "some Chinese poets are searching for a lost language".

He says that during that period, poets began thumbing through books of foreign poetry in a move to cast off the traditions of classical Chinese poetry.

"Not from language necessarily but from the message, you still get the idea that before '49, poets had difficulty writing perfect poems," Kubin says. "Lu Xun was very good at writing good classical poems, but his modern poems are terrible."

But at the end of the 1970s, poets began another search for a new voice and revisited much of what had been done before '49, including several "excellent" translations of poems from countries such as Spain, England and France.

"In my eyes, it was only after '79 that you had a lot of young Chinese poets who are able to master not only the neirong (content) of poetry, but also the language part of the poetry," Kubin says. "After '79, they wanted to renew Chinese poetry."

And Kubin believes they have succeeded.

"Today," he says, "there's not so much difference between Chinese poets and foreign poets."

However, he believes the genre's legacy won't be determined by its poets alone.

"It depends on the readers, on the people, if Chinese poetry will have a chance or not."

(China Daily 12/07/2007 page20)