Pushing boundaries with the scrawl of nature

Li Keran (1907-89) is widely viewed as one of the most innovative and influential artists and art educators of the 20th century China.

"Like his predecessors such as Huang Binhong, Lin Fengmian and Xu Beihong, Li has painstakingly tried to find his own voice amidst rich traditions, strong Western influences and a fast-changing reality," says Fan Di'an, curator of the National Art Museum of China.

A grand exhibition is being held at the museum to commemorate the 100th birthday of the artist who successfully pushed the boundaries of Chinese ink painting.

Jointly organized by the Ministry of Culture and the Li Keran Art Foundation, the exhibition occupies seven halls of the museum and is reportedly the largest retrospective show of the artist's works.

At the core of the exhibition are some 80 selected signature ink landscapes, figure paintings, seals and calligraphic scrolls.

Also on display are a large number of Li's pencil sketches, ink painting drafts, letters, old photos, manuscripts and books, alongside ink works from a roster of Li's students and other artists who are heavily influenced by Li's style.

Meanwhile, a three-day international academic seminar was convened early November in Beijing on Li's artistic legacy.

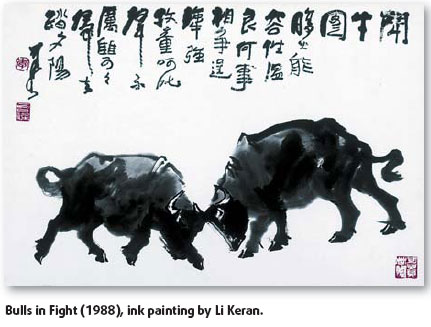

For ordinary Chinese, Li is best known for his vivid depiction of Chinese buffaloes and historical figures.

But "among art circles, Li is highly respected for his accomplishments in modern landscape paintings," says Shao Dazhen, a renowned art critic.

Throughout his lifetime, Li "kept a calm and open mind, refusing to copy other artists but keen to absorb ideas from other art genres - even from Western art," says critic Liu Xilin.

Li transformed traditional literati Chinese landscape painting into modern landscapes that are more attuned to the taste of modern viewers, Liu says.

In his paintings of imposing and towering mountains, fleeting fogs, colorful clouds and lush forests, Li applied condensed brushstrokes and multi-layered dark ink to convey a sense of movement.

He often used lighter ink for the edges of the mountains, generating dazzling effects of light and shadow, a novel approach that was not employed by previous Chinese landscape masters, critics say.

Borrowing from Western art traditions, Li emphasizes the importance of outdoor sketching.

"After carefully studying Li's sketches from nature and his thoughts on sketches and the relationship between natural beauty and artistic representation, I have come to see that, as an innovative artist, Li highly values Mother Nature," says art historian Shui Tianzhong.

And "very often, the final works are done on the basis of several sketches, because he always tries to put into one picture the very best tone, composition, light and shadow and coloring he can figure out," says Li's son Li Xiaoke, an ink artist in Beijing.

During the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), Li suffered from the political upheaval and was forced to stop painting. But he managed to practice in secrecy, improving his skills in traditional Chinese calligraphic art that he later applied to strengthen the lines in his modern Chinese landscape paintings.

After its Beijing debut running until today, Li's paintings will move in early December to Xuzhou, Li's birthplace in East China's Jiangsu Province, where a series of commemorative events will go through December 20.

(China Daily 11/14/2007 page18)