Where all paths crossed

|

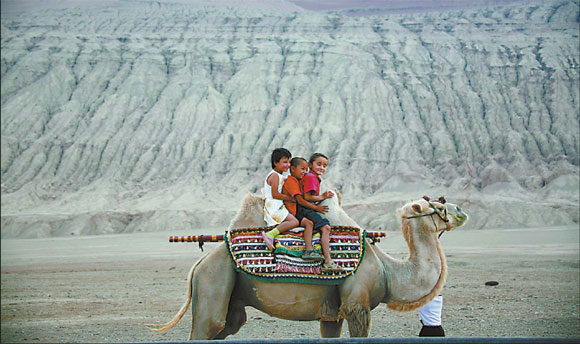

Young visitors take a camel ride at the foot of the Flame Mountain in Turpan. File photos |

On an early June day, two 8-year-olds were playing in front of Zhang Youhe's home. Just when Zhang opened his door, he saw something which was too late for him to stop: An ox-driven cart sped by and ran over the children, breaking the bones in their lower body. The driver, Kang Shifen, was hauling bricks for his employer.

Kang promised to pay the medical bill and, were the children to die from the accident, agreed to take all legal responsibilities.

The case was heard in court from June 4 through June 22. The judge ordered Kang out on bail, but on condition that his two guarantors receive 20 lashes were Kang to jump bail.

This sounds like a regular traffic accident even if the penalty is a little unconventional. Only, it happened in AD 762, one year before Byzantine troops invaded the Papal States. It involved at least three ethnicities - the Sogdian children, one of whom was named Jin, the 30-year-old Turk driver and the eye-witness, who was Han.

The court document detailing the above story is among 2,000 scrapes of paper unearthed in Astana, 40 kilometers east of Turpan, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in Northwest China.

Since the 1950s, more than 450 ancient graves have been exhumed as part of 14 excavation projects. The uncovered words have been deciphered as belonging to as many as 24 languages. The scrapes range from business contracts to personal correspondence. But the strange thing is, they were not stored in a library, but as paper artifacts that accompanied the dead. The above document was actually folded into a belt that was tied around the waist of a deceased. There were also paper hats and paper shoes, all with written words on them.

Why did people 1,245 years ago put used paper as a kind of origami sacrifice? Archaeologists are still searching for an answer.

But one thing is for sure: Turpan was once the center of the world, where the most trafficked route, the Silk Road, passed through all four great civilizations - Chinese, Indian, Islamic and Greek-Roman - converged. According to Ji Xianlin, an eminent scholar, this is the only place of such convergence.

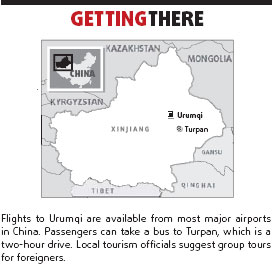

Today's Turpan is a mid-sized city 183 kilometers east of Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang, with a population of half a million. Longer than the 6,400-kilometer Silk Road is the New Euro-Asian Continental Bridge that runs through here, starting from Lianyungang in East China's Jiangsu Province on the coast of the Pacific Ocean all the way west to Amsterdam by the Atlantic Ocean. Few business travelers today would drive the entire 10,900 kilometers.

Today, the city is synonymous with grapes. Pockets of oasis in the valley have made it a fertile land for furrows of trellises to form archways and hundreds of varieties of grapes to grow.

But apart from these watered plots, Turpan is a place of dry, hot land and equally dry, hot air. Traces of ancient history are preserved mainly because of this topography.

Turpan lies some 150 meters below sea level, the lowest point in all of China. It is both the hottest and driest place in the nation. Annual rainfall averages 16 mm while 3,000 mm is evaporated.

The Anasta graves were the burial ground for Gaochang, a city built in 104 BC by Han Chinese. As legend goes, the emperor of the time sent an army across the Gobi desert. They were not allowed to return home when their mission failed. They had to make do by building their own replica of the capital of the Central Plains, which was then China proper.

By AD 640, the army from the Tang court descended upon the city state. The local king was literally scared to death as he was engaged in some foxy tango of border politics between the Tang empire and a nomad kingdom. The Tang emperor got hold of the recipe for growing grapes and recreated a vineyard in the backyard of his palace. Gaochang music was also very much in vogue in the Central Plains. Aristocrats enjoyed textiles from Persia, cotton from India and jade from other central Asian countries as goods flowed freely through Turpan.

From the ruins of Gaochang, where most buildings had vanished in the aftermath of the clash of civilizations in the 13th century, the northwest gate is relatively intact, and two temples in the southeast and southwest parts of the outer city are clearly visible.

Ten kilometers west of current downtown Turpan lie the ruins of Jiaohe, another city even older than Gaochang. It was built 2,000-2,300 years ago by the earliest known settlers in the region called Cheshi. Nobody knows where they went or how they evolved.

The city stretches 1,760 meters long and 300 meters wide. What makes it unique is its location: It sits atop a 30-meter-high sandbank, surrounded by a bifurcating river and steep cliffs, leaving only one entrance. Hence the strategic significance for Jiaohe, literally meaning "enclosed by a river".

There is recorded history that between 108-60 BC there were five military campaigns between Hans and Huns. In the end, the Hans won Jiaohe. But the earliest builders are believed to be of European descent.

One has to use imagination in order to conjure up the splendor of Jiaohe. But it is not too difficult. Much of the frames of the buildings, except the roof, are discernible. There are three clear-cut districts - government, residential and religious. The Buddhist temple is reminiscent of a European town square.

Most structures were created not by laying bricks but by carving into the clay, a practice common in Gansu and Shaanxi provinces in Northwest China. Since hardly any rain falls in the area, there is no threat of the washing away of layers of mud.

Some courtyards had wells, and the inner rooms were carved to shelter from the scorching sun. But why would thousands of people live on top of a dry highland while they could have a much more enjoyable life down by the riverside? The only plausible reason is defense. The walls along the main boulevard are 6-7 meters thick, with no windows facing outside. This city must have faced barrages of attack in its history.

Standing among the ruins, one cannot help wondering what was going through the mind of a typical Jiaohe resident during the 1,500-plus years when it was an international metropolis. Would they know their fortress might also be their curse as the mass grave of 200 babies seemed to ominously portend? Would they know their conquerors would abandon the city, after possibly a slash and burn rampage?

Turpan, or Xinjiang in general, has a rich and varied landscape that has inspired much song, dance and poetry. It is also the place where people of all races converged, clashed violently, and ultimately lived in peace with one another. While the ruins tell the historical truth, there is plenty of blank space to be filled with imagination.

(China Daily 10/11/2007 page19)