Setting the stage for Qinqiang

To an outsider, Qinqiang Opera may sound harsh and exaggerative. But for many people from Northwest China, it is something they just can't live without.

"In my hometown, when a baby is born, the family holds a dinner party and invites a Qinqiang troupe to perform. When a person dies, the family also invites a Qinqiang troupe to perform at the funeral. Qinqiang is what we hear first and last in this world," says Liu Xiang, a 32-year-old accountant from Shaanxi Province.

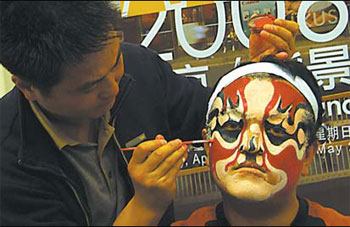

|

Troupe members help each other do makeup before a performance. |

Chang Zhimo, a 57-year-old engineer from Gansu Province, believes the opera transmits positive morals to the next generation. "Babies sing along with adults and learn such lessons as 'good will be rewarded with good and evil with evil' from Qinqiang," Chang says.

Yun Shizhong, a 62-year-old retired librarian from Qinghai Province, believes the musical form appeals to ordinary people. "Qinqiang is an opera of the poor, and it is performed in their way," Yun says. "It provides them an opportunity to vent their pent-up feelings. When a character in Qinqiang Opera is sad, he would literally beat his chest and howl."

Liu, Yun and Chang all believed something was missing from their lives after they moved to Beijing until they discovered the Great Qin Opera Youth Society of Beijing.

Founded in 2004, the society is the only Qinqiang organization in the capital. The society is made up of about 40 members who came from Northwest China and work in various fields in Beijing. Aside from its elderly band members, most of the singers are in their 20s and 30s.

Although Qinqiang is an ancient art form, it was the Digital Age development of the Internet that brought them together.

In 2003, a group of Qinqiang fans met through the China Qinqiang Net website (www.qinqiang.com) and came up with the idea of forming a Qinqiang troupe in Beijing. And on November 7, 2004, the Great Qin Opera Youth Society of Beijing was founded.

Since then, the members have been studying and rehearsing Qinqiang on every Sunday without taking a day off. And rather than taking a break over the May Day and National Day golden weeks, they instead met twice a week.

Yun, who used to be the deputy director of the Qinghai Provincial Library, came to Beijing to live with his daughter after retirement. A lover of Qinqiang since his childhood, he did not have much time to indulge in it when he worked in Qinghai. In order to enrich Yun's life in Beijing, his daughter searched for Qinqiang activities on the Internet and found the Great Qin Opera Youth Society.

Now, Yun is a banhu (two-stringed fiddle) player of the society. Although the commute from Yun's home to the rehearsal room is two hours one way, he still makes the voyage every week. "I feel at home when I play Qinqiang here in Beijing," Yun says. "Members of this group come here not only for fun but also with a mission to promote the art form to more people."

Zhang Jianfeng, a 25-year-old office worker, is one of the society's youngest members. A native of Shaanxi, Zhang enjoyed listening to Qinqiang since childhood, but it was at the Great Qin Opera Youth Society of Beijing that he sang Qinqiang for the first time.

"The society provides us great opportunities to practice, and I feel encouraged by the friendly atmosphere here," says Zhang. "Through our shared love for Qinqiang, many of us have become very close friends."

The society had no regular venue in its earlier days, and it rehearsed at the Xihaizi Park, in Tongzhou District. Curious onlookers would gather around, and the society was able to recruit new members from passersby.

However, the crowds eventually made practicing in the park too distracting, as the audiences would become impatient when actors would pause to discuss their performances. They would interrupt them, asking them to continue singing.

One time, one of the singer's sudden shrieks scared a small child who began to cry, and the tot's grandfather argued with the performers for a long time.

So, last year, one of the group's members offered them rehearsal space in the factory he owned in the Dougezhuang area of Chaoyang District. The location is not convenient for many members to commute to, but it provides a setting in which the performers can perfect their stage presence undisturbed.

Under the leadership of the society's artistic director Liu Xiang, who is a student of Shaanxi's famous Qinqiang actor Wang Fusheng, the members have rehearsed many classic excerpts and have run through the full play of An Emperor's Son-in-Law Put to the Chopper (Zha Mei An).

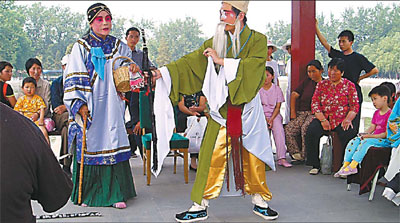

|

A performance at a Beijing park draws curious onlookers. Photos by Li Peifeng |

"Our society has a complete lineup of all the role types, which is rare for an amateur Qinqiang troupe, but at the same time, we are looking for some more band members, especially in the percussion section," says Liu. "We will first rehearse some of the classic Qinqiang plays, such as Orphan of the Zhao Family (Zhaoshi Gu'er)."

In June 2005, the Great Qin Opera Youth Society of Beijing staged their first public performance at the China Agricultural University. And in December of the same year, they performed at the Beijing Normal University. Both performances were warmly received by the audiences that packed the halls to capacity. Patrons included not only students interested in traditional culture but also Beijing residents who hailed from Northwest China.

In October 2006, they toured to Xi'an, the epicenter of Qinqiang, and gave a performance at Yisushe, one of the most prestigious Qinqiang venues. Most elderly Qinqiang artists in Xi'an came to the performance and affirmed the society's achievement.

Until now, the society was self-funded through member's donations. They paid for their instruments, costumes and the trip to Xi'an. There has been no other financial support aside from a grant of 1,500 yuan ($200) from a restaurant called Qinhong Shifu, the owner of which is a Shaanxi native. In return, the society's executive director Li Peifeng shot a commercial for the restaurant and played it for their audiences at Beijing Normal University before the society's performance there.

"We hope we can find more support, because it costs a lot to rent professional costumes for a formal performance," Li says. "We lose money every time we perform."

Li, an independent film director, is also shooting a documentary about Qinqiang. "Besides studying the ancient performing art, our society is responsible for making Qinqiang relevant to contemporary times and a broader audiences," Li says.

To celebrate the society's third anniversary, they plan to give a performance of the play An Emperor's Son-in-Law Put to the Chopper at Peking University in November.

(China Daily 10/11/2007 page18)