I ink, therefore I am

|

| Rhythms of Autumn (Qiu Se Ban Lan Tan Zhuang Mei) by Chen Jialing |

Chen's works are so controversial that at a recent seminar on his latest ink works, artists, critics and scholars from Beijing and Shanghai were widely divided.

Some say that Chen has pushed the boundaries of Chinese ink painting too far. Some critics even claim that Chen's innovative ink works are "Western-influenced, fake ink works", because they look like graphic designs.

Upon first sight, many parts of his works are wrought without resorting to traditional brushwork and stylized painting rules.

"My ink works are like my children, and they are full of life; I have poured my energy into their creation," contends Chen. "I would say that my ink paintings are all done with a genuine respect for Chinese culture. They are works deeply rooted in Chinese traditions."

Fan Di'an, president of National Art Museum of China, calls Chen "a self-conscious innovator of Chinese ink art". As early as the 1980s, American art scholar Joan Lebold Cohen had discussed Chen Jialing's innovative ink art in her essay The Spectrum of the New Generation.

"Although Chen Jialing comes from the venerable 1,000-year-old tradition of bird-and-flower paintings, he is one of the most original and lyrical practitioners of that genre," Cohen writes.

For years, Chen has been hailed by the local artistic community in Shanghai as a key figure of the emerging New Shanghai Painting School, which includes Qiu Shude, Lu Fusheng, Yang Zhenxin and Zhang Guiming, among others.

The original Shanghai Painting School refers to a modern Chinese painting school, which emerged to prominence since the late 19th century. It was a period when modern Chinese society was shaken by drastic changes under Western influences first imposed by invading warships, seafaring merchants and Christian missionaries.

The Shanghai Artists Association has organized Chen's solo exhibition, the first in China and the largest so far, at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing, which concluded last Saturday. It will reopen at the Shanghai Museum of Fine Arts on September 18 and runs through National Day Holidays.

The solo exhibition encompasses some 100 selected works of ink figure paintings, bird-and-flower works, sketches, photos, and ceramic and porcelain works Chen created over past decades.

What impresses the viewers most might be his varied, poetic and minimalist depictions of trees swinging in the wind, dreamy imageries of lotus flowers and fish, and lovely birds whose shapes are realized mainly by the artist's deft use of empty spaces.

The lotus flower has also been a favorite subject for Chen. "The depiction of lotus flowers demands almost all the basic visual elements of Chinese ink art," he says.

According to traditional Chinese culture, the lotus flower symbolizes a person of virtue and moral integrity, and has become popular for both artists and collectors.

The older works on display clearly reveal Chen's solid training in traditional ink painting. In the early 1980s, his works were widely accepted as traditional types, however, in 1987, Chen ventured to make changes, which brought condemnation from his former teachers and classmates. They thought the changes were "suicidal" to his artistic career.

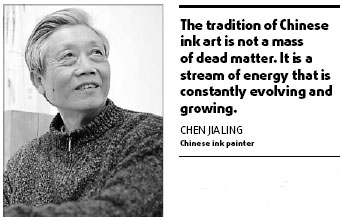

"I see tradition very differently. The tradition of Chinese ink art is not a mass of dead matter. It is a stream of energy that is constantly evolving and growing," says Chen.

He still remembers an exhibition in 1985, when his paintings of lotus flowers attracted attention from several Western connoisseurs who said they saw something different in his way of depicting the subject. "That prompted me to further explore the possibilities of Chinese bird-and-flower painting," Chen recalls.

Born in 1937 in Yongkang County, East China's Zhejiang Province, Chen's early interest in art was warmly encouraged by his parents, who were primary school teachers.

He studied figure painting with master Pan Tianshou in the Chinese Painting Department, Zheijiang Academy of Fine Arts from 1958 to 1963. In the 1970's, he studied Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy with Lu Yanshao.

Soon after he graduated from Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, he was thrown into the whirlwind of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). But Chen made great efforts to concentrate on his pursuit of ink art.

Proud of his innovative works, Chen also admits that he owes much to his teachers and that the strict and thorough training in terms of traditional techniques and aesthetic principles have left indelible imprint on his heart.

"My works today look not much like those by my former teachers such as Pan and Lu. But I think I have learnt the best of their art," Chen says.

"High quality gongbi painting requires a good use of lines. One must understand that the dots, patches and lines in ink paintings are not executed randomly but rather, are placed according to certain rhythms," Chen explains.

"Observant reviewers can read music from a good piece of ink painting. The best lines in an ink work must be rhythmical and full of vitality."

When describing his own creative procedures, he often says: "My best ink works are realized in collaboration with God."

He would stamp many of his lotus flower paintings with a seal carved with the Chinese character Yu Shang Di He Zuo, literally meaning "Collaborating with God".

Chen says that he refers to God here as the unknown and unpredictable factors that shape the final effects in his paintings.

He is very keen to create works that cater for the taste of people today.

The flowers in Chen's ink works are always rendered on large pieces of rice paper. This is meant to correspond with the reality that people today like to decorate their spacious houses with bigger Chinese paintings, Chen admits.

Also, his ink works often assume a minimalist style and are painted with seemingly simple compositions, with deceptively casual dots, lines and richly textured patches created by a perfect interplay between ink, water and brush.

Also, as many modern Chinese in urban centers have a fast-paced, routine lifestyle, they are yearning for art works that are visually refreshing - a demand Chen has answered by applying bright coloring to some of his works.

"Artists must answer the call of the times, otherwise he or she would be left behind," Chen explains.

(China Daily 08/30/2007 page20)