Big screen, big bucks

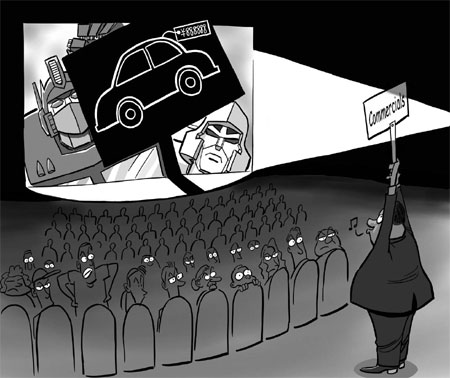

Chinese Transformers fans waited 20 years for their favorite 1980s cartoon series to come to the big screen. But filmgoers soon realized they had to wait another 20 minutes, thanks to the growing pre-show advertisements.

Although the cars and printers in the pre-show advertisements transformed into robots to resonate with the audience, what people wanted to see was the movie itself.

"We went to see the film, not the ads," says Liao Yang, a junior college student, after watching the picture.

Despite audience's protest, cinema advertising, since its debut in China in the late 1990s, is becoming an effective way to make a film more profitable.

In the early 1990s, China set the quota of importing 10 international films to cinemas every year, which was later expanded to 20, and blockbusters such as True Lies and The Lord of the Rings attracted record audiences. In 1997, the first cinema advertisement was screened prior to Dante's Peak.

When Zhang Yimou's Hero was sweeping the box office in 2002, the cinema commercials attached to it earned 20 million yuan ($2.6 million).

Cinema advertising in China works differently compared to the West. If an enterprise wants to screen the ads of its product before a film, it usually finds an agency that deals with the film's producer, distributor and theaters to negotiate for the ads' slot, length and price. The fees go to the exhibitor, the distributor, and the film's producer.

In the United States, cinema advertising time is more flexible. It can be purchased locally, regionally or nationally. It may also be linked to certain categories of film, such as those rated PG or R, or even to specific film titles. All this allows the smaller, local advertisers to appear on the big screen at very affordable rates. Usually it is just between agencies or enterprises and the theaters.

Many enterprises choose to launch cinema advertising because of its low cost and unique communication effect.

In China, to launch a 30-second ad in a film screened nationally costs about 1.5 million yuan ($197,000), says Zhang Qingyong, CEO of FilMore Media Group, one of the largest agencies of theater advertising in China. Meanwhile the cost to sponsor a TV series aired by China Central Television (CCTV) during prime time reached 70 million ($920,000) last year. What to bear in mind, however, is the different audience. CCTV's programs reach about 5 million households now in China.

Besides, cinema audiences are captive, attentive and usually appreciative. The cinema is an experience, consisting of many elements from "previews to popcorn" and the advertising is very much part of this total entertainment package.

There is no distraction. When people sit in a dark space and concentrate on nothing but a big screen, they tend to focus on the content, enhanced by the audio and visual effect that a TV ad cannot compare to.

Cinema audiences cannot change the channel, says Yan Ming, who designed a truck commercial specifically for Transformers.

However, there are setbacks.

Firstly, a movie ticket costs about 50 yuan ($6.57) in China, two or three times that of a DVD's price, which deters many from the cinema.

The uncertainty of the film's screening time is also an important reason. Cinemas will adjust the screening time for films according to their performance on box office, and sometimes a film planned to screen for two weeks ends in five days.

And unexpected events can happen.

In 2005, Steven Spielberg's War of the Worlds was supposed to screen simultaneously all over the world, including China, on June 29, but it was postponed to August 11, followed by another postponing to August 25. It was eventually shown on August 20 in China.

In 2006, Chinese theaters halted screenings of The Da Vinci Code in light of protests by China's Catholics.

"If the clients had some seasonal products or new brands to promote in that period, they would feel very frustrated," Zhang says.

Even if all the films were screened on time, there is so far no effective supervision on its effects, Zhang adds. It's impossible for every enterprise to send someone every time the film is screened to see whether their ads are shown and what the audience reaction is.

In addition, Hollywood and national blockbusters are usually full of ads, while middle and small budget films find it hard to attract commercials. As a result, 80 percent of films attract no ads, while 20 percent are so filled with ads that they annoy audiences, says Zhang. The theaters thus find it hard to maintain a stable income from the advertising.

Zhang and his agency, therefore, are trying to figure out a new on-screen advertising model for his clients.

Called "screen matrix", this new model features a network of about 100 top cinemas in China's 20 major cities. FilMore, in direct cooperation with the theaters, provides different packages for its clients on the basis of time intervals.

Advertisers can show the ads for a month or half a month, covering all films screened in the theaters within the time. The company supervises the broadcast of the ads and provides feedback on the viewers' response.

The half-month package for a 30-second ad shown in 100 cinemas before Spiderman III cost 880,000 yuan ($116,000). Thanks to the long screening time for the blockbuster and multiple screens in each venue, the average price for each screening costs only about 20 yuan ($2.63).

Zhang's agency is one of a few that are building up a network of theaters. Most agencies in China are doing it the traditional way by dealing with not only the cinemas, but the producers and distributors.

In the 1990s, China's on-screen advertisements used to screen not only before the film starts, but also in the middle of the movie. Cinemas would stop the film midway and show ads.

In 2004, the State Film Bureau issued a regulation that all on-screen spots should be shown before the film. However, there is no governmental regulation on a cinema ad's length and content. The current regulations on other kinds of ads apply to cinema advertising, too.

Jiang Ping, vice president of the film bureau, says he had no comment of the situation. "Let the market decide," he says.

(China Daily 08/16/2007 page20)