Catching a killer

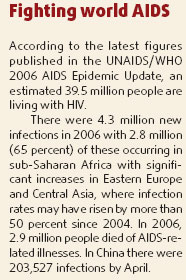

Twenty-six years after the first five cases of a novel immunodeficiency disease were described, the AIDS pandemic has become the world's biggest public health crisis. In order to end this epidemic, scientists have been trying to develop a vaccine. However, countless failures have smashed their hopes again and again.

"Once in a while, the feeling of desperation dominates the scientific world as the arrows of vaccines seem to always miss the targets of AIDS virus," says Zhang Linqi, director of AIDS Research Center of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

IAVI, a global none-profit partnership working to accelerate the development of a vaccine to prevent HIV infection and AIDS, estimates that the potential positive impact of AIDS vaccines would be enormous, especially in the developing world.

It is estimated that if a vaccine is introduced in 2015, the high, medium and low scenario of vaccine introduction could slice new infections by 70 percent, 50 percent, and one third respectively by the year of 2030.

According to doctor Zhang, to "counteract one toxin with another" had been a traditional Chinese medical philosophy to prevent infectious diseases. In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Chinese doctors learned to prepare the smallpox scar taken from the patients into powder. The powder was then blown into the noses of healthy people, who would be immune from the disease.

In 1749, Edward Jenner, an English country doctor, started a new page in the history of fighting against infectious diseases. He injected the smallpox virus taken from the cow into human bodies to prevent the infections of smallpox. Jenner became the father of modern immunology.

Historically, vaccines have been the greatest success story in the prevention and control of infectious diseases. The achievements include eradication of smallpox, progress toward elimination of polio and measles, and control of diseases such as tetanus, diphtheria, and whooping cough.

A vaccine is actually a substance that is introduced into the body to prevent infection or to control disease due to a certain pathogen, such as a virus, bacteria or parasite, which teaches the body how to defend itself against a pathogen by creating an immune response.

However, different from the viruses of common infectious diseases, HIV is hypervariable due to its rapid replication rate, high mutation rate and capacity for recombination. The hypervariability of HIV poses a great challenge for vaccine developers. It makes HIV a moving target, so by the time the vaccine candidate has been designed, developed, and tested in clinical trials, the virus may have evolved.

Though the challenges in developing an AIDS vaccine are numerous, scientists still believe that it is quite possible. The belief is based on several bright sides of findings, according to doctor Zhang.

First, a small number of individuals remain uninfected despite good evidence of repeated exposure to HIV.

"For example, some sex workers in Africa would not get infected by HIV. The group of people is quite important for us to get a better understanding of the pathogen of the disease," says Zhang.

Second, robust anti-HIV cellular immune responses found in some rare individuals can suppress viral load to undetectable levels, slowing the progression of disease and inhibiting HIV transmission.

Third, in the normal course of HIV infections, the immunity suppresses the viral load for a substantial period of time, often a decade, to finally progress into AIDS.

Last, it is found that broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV can completely protect monkeys from infections.

Right now, though there is no vaccine to protect against HIV/AIDS, doctor Zhang believes that it is likely that the vaccines could offer some form of protection, such as slowing the rate of progression to AIDS for those who become infected with HIV.

Now the scientific field is eagerly anticipating the data from two AIDS vaccines trials, hopefully coming out in 2008-2009. One is a Phase III trial from Sanofi-aventis-VaxGen conducted in Thailand to induce humoral immune responses. The other is a Phase IIb trial from Merck, the first real test of a candidate that induces robust cell-mediated immune responses, conducted in more than 20 countries.

Besides eliciting antibodies to neutralize HIV or cell-mediated immune responses to blunt viral load to undetectable levels, there seems to be no third road to take in developing an AIDS vaccine at present, according to doctor Chen Ling, director of Guangzhou Institute for Biomedicine and Health.

"Expectations on the data of the two trials, particularly the latter, made the scientific community a bit more optimistic. We hope the trials will translate to either some degree of protection or at least slow down the disease progression," says Chen, who once worked at Merck and was the inventor of one of the key patents of the vaccine at trial now.

But on the other hand, vaccine scientists like Chen are making preparations for the possible failure of the two trials. They are researching new generations of vaccines.

"The acting theory of the new generation of vaccines is similar to the previous generations, but they are more safe and effective. To dig the full potential of the vaccines or their combinations to achieve the best outcome is what we could only do now," says Chen.

As a vaccine researcher coming back from abroad, Chen feels AIDS vaccines research in China is developing rapidly during the past years owing to more government support and more research talents like him coming back home.

Now the first AIDS vaccine in China, developed by Changchun Baike Pharmaceutical Company Limited, had already completed phase I clinical trial of testing the vaccine's safety in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

According to Chen Jie, supervisor of Guangxi AIDS vaccine trial, within one and a half years, a total of 49 healthy volunteers received the vaccine inoculations and none of them was found with safety problems. Now a phase II trial of testing the vaccine's immune response is waiting for the approval of the State Food and Drug Administration.

Besides, another phase I trial of Tiantan vaccine is already approved to be conducted at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMC) in 2008. Several other AIDS vaccines were either under research or waiting for the approval of clinical trials.

Doctor Zhang emphasized that healthy people recruited during the first two phases of AIDS vaccines clinical trials are 100 percent free from infection risk of HIV. However, there might occur some side effects, such as fever and swollen sign at the injected area.

(China Daily 08/15/2007 page19)