All hands on deck

|

|

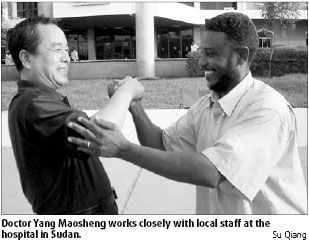

The Director of the Chinese medical team in Sudan Mo Jianping (left) and his colleague Wu Changxue operate on a Sudanese patient in October 2006. Courtesy of Cui Xiaogang |

"Working here is not easy, away from my family, with hard working conditions and totally different cultures," says Mo, who joined the Chinese medical team in Sudan from 1999 to 2001 and came back again in August 2005 for another two-year term.

Mo, 51, but looking like someone in his 30s, is one of the 36 Chinese doctors working in Omdurman Hospital and a field hospital. It is also called the Chinese hospital or friendship hospital by locals, as China provided the equipment for its construction in the 1990s.

Like Mo, all his colleagues are from Northwest China's Shaanxi Province as Chinese medical teams in Africa follow this rule: A specific province is in charge of a specific country.

More than 1,000 doctors from Shaanxi have served in Sudan since the first medical team arrived in Khartoum in 1971.

Currently, more than 1,000 Chinese doctors provide medical services in 42 African countries.

Since 1963 when the first Chinese medical team arrived in Algeria, the Chinese government has sent more than 16,000 doctors to 45 countries or regions, where they, along with local doctors, have treated more than 200 million cases.

The Chinese doctors in Mo's hospital may come here out for different reasons, but they all agree that, as a doctor, working in a place where they are most needed is something worth doing.

Cui Xiaogang, an anesthetist, took his inspiration from teachers and colleagues and made a decision for which he says he would never regret.

"My decision was inspired by my teachers when I was a university student, since most of them worked in Sudan and loved the country," says Cui, who got his master's degree from Xi'an Medical University.

"One of my teachers who stayed in Juba of southern Sudan for one year told me: 'Although I got sick and almost died there, I don't have any regrets about my decision. If you don't go there, you may regret it for the rest of your life'," Cui says.

Cui works in the anesthetics department, one of the busiest departments in the hospital, because there are many surgery cases and very few qualified anesthetists in Sudan.

Many patients in his hospital have to wait for more than three months for operations.

Everyday Cui has to treat, or advise other doctors to treat, 15 patients, which means there is almost no time to rest from 8:30 am to 2:30 pm. During the night he has to deal with emergency cases.

To communicate with patients, the Chinese doctors have learned some useful Arabic words.

It is easy for a surgeon to know what happened to the patients, but for a physician, he needs to communicate with them to know what he or she is feeling.

"For some special cases, we still need a translator to avoid misunderstanding, which could cause severe problems," Mo says.

Their professionalism has earned them respect from local people.

"It is a good hospital with a clean environment and nice doctors," says Abobakr Ali Mohamed Salih, who lives nearby the hospital.

In treating local people who could not speak English, the doctors can speak some Arabic words such as "open your mouth and show your tongue", says Salih, whose father received treatment there.

But Salih says the hospital needs more nurses and equipment such as ambulance and beds.

According to their contract, Chinese doctors only have to provide medical help, but they are sometimes invited to share their ideas with Sudanese staff about the management.

"Whenever we find problems or rooms for improvement in our hospital, we won't hesitate to talk with our Sudanese colleagues," says Mo, who is also director of Chinese Medical Team in Sudan.

"They also show their interest in our suggestions."

Mo meets with the president of the hospital once every month and topics range from management, medical services, equipment updating to human resources.

"The meetings let us not only know the problems in our hospital better, but also improve our understanding of each other," Mo says.

Outdated equipment is one of the biggest headaches that Mo and his colleagues have to face every day.

Although China donates $40,000-worth of equipment each year and sends technicians to fix old machines, it still couldn't meet the demand.

"It is not uncommon that sometimes the scissors cannot hold the artery," Mo says.

"Many operations which would be an easy job in China could turn out to be a very difficult one in the hospital."

The ups and downs they experience at the hospital prompted them to come up with new ideas to improve the Chinese medical services there.

For instance, currently China is taking an all-come-and-all-go policy, which means all Chinese medical staff will be replaced by a totally new team every two years.

"With all the members of the former team going back to China, the new team have no Chinese doctors to consult with and have to spend half a year adapting themselves to the new working environment. That is not good," Mo says.

Mo and his colleagues have submitted a new proposal to the Chinese Ministry of Health, to make the Chinese Medical Team "permanent".

Mo says that if half of previous team goes back to China every year while the other half stay for one more year with the new members, there will always be some doctors with at least one-year working experience in Sudan.

"We already submitted this proposal to the Ministry of Health. And I believe they will seriously consider our idea because that could help maximize our contribution in Sudan," Mo says.

(China Daily 08/10/2007 page20)