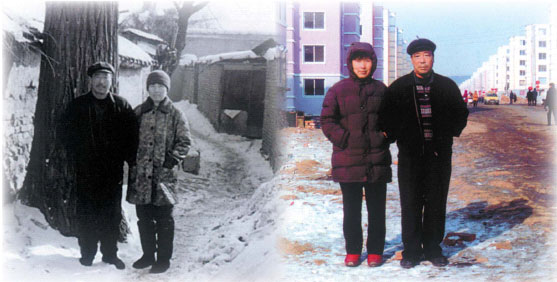

Then and now: Sea change in landscape

Wang Zhanying, 57, and her husband, Zuo Shutang, 59, pose in front of their old Xindihao home, and again in front of their new home in 2005. Courtesy of Wang Zhanying |

Modigou had not seen a young woman moving in for a long while. In this valley, people set off firecrackers for celebration when their daughters moved away after marrying somebody from outside the community. It was almost unthinkable for an outsider to marry in. It would be like a jump into hell.

The community of 1,376 households was a shantytown of the worst kind. Makeshift huts lined both sides of unpaved roads, leaving zigzagging paths. Worse yet, the road, if it could be so called, was higher than the floors of the shacks because decades of burnt coal had piled up. In the words of locals, whenever there was a rainstorm, there would be drizzle indoors. In the winter, freezing cold would penetrate every crack and gaping hole in the walls, leaving the stove an isolated spot of warmth.

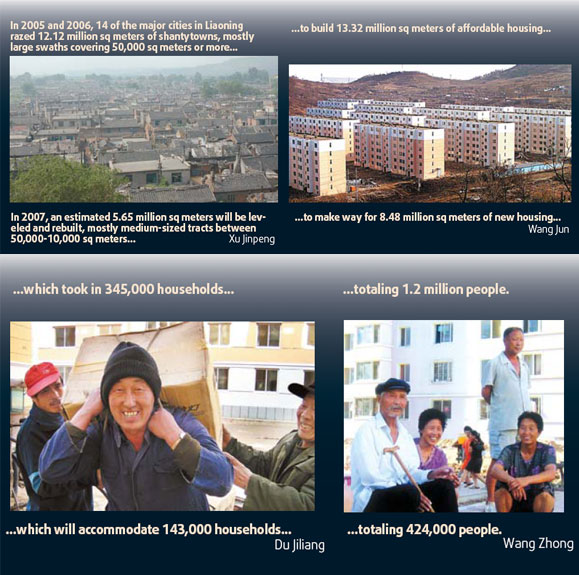

There were 81 such ghettos in Fushun alone, inhabited by 95,600 households totaling 320,000 people, accounting for close to a quarter of the city's population. Province-wide, there were some quarter million households crammed in sprawling shantytowns by the end of 2004.

That was the time Li Keqiang paid the first of his three visits to Modigou. Only 12 days into his new job as secretary of the Liaoning Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China, Li was touring shantytowns in the city. "Show me the poorest place," he asked.

Jin Guixiang (left) and her three-generation family used to inhabit a 30-sq-m shack in Wanghua District. On November 11, 2005, they moved to Room 501, Unit 4, Building 55 of the renovated community, which is twice as large as their previous home. Zhang Bo |

"Modigou," replied a local official, but then hesitated. No vehicle dared, or could, enter this slum. Even taxis did not go there -- not that people there could afford one. In 29 C below zero, Li and his lieutenants trekked into one shack after another.

"I was shocked," Li recalled two-and -half years later. He remembered vivid details about a family of six crowded in a cramped room, both sons jobless, an old lady sitting on her bed, draped in her blanket, shivering.

Visibly moved, he told the residents that "Some difficulties could be solved when the government clenched its teeth, but for those suffering from poverty, these could be insurmountable hurdles."

It was also on this occasion when he swore his determination by uttering "smashing pots and selling iron" - meaning to use all means necessary - to address the issue of "slum clearance", known as peng gai in Chinese.

Origin of plight

The shantytowns started to take shape in the 1950s and 60s when the mantra was "Work first, live later". The earliest workers were assigned dorm-like units. Slowly, their children grew up and needed to move out. Since there was hardly any new construction during the era and families usually worked at the same factories, the children erected ramshackle shelters around the existing buildings. There was no heating, running water, sewage, or street lamps, but they spread like a wildfire, covering tens of thousands of square meters at a stretch.

Since the 1980s, there were sporadic efforts at peng gai. The results were less than satisfactory. Around 1990, State-owned enterprises chipped in and tore down some tracts of slum housing. Although the housing market took off elsewhere, no developers would step forward to take these projects because the land had gained little commercial value. The few who attempted urban redevelopment ended up charging prices that hardly any resident could afford.

Before the 20th century drew to a close, there was a mandate from the central government to eliminate all urban ghettos. But without financial backup, it just remained a slogan. Only a few places along high-visibility highways were razed.

When the current peng gai drive was first launched, there was suspicion on the part of residents. Many were reluctant to make room for the bulldozers. But as the first bunch of slum dwellers moved into apartment buildings that sprouted on the tracts of dust, sludge and debris, people did not need further convincing. This time, it was for real.

New world

New world

Huang Renmei has lived in Modigou since the 1950s. She and her husband, a sand-and-cement mixer operator, are retired and subsist on a combined pension of 1,100 yuan ($145) a month. They moved out of their old 20-sq-meter shack in early 2005 and moved into their new 45-sq-meter apartment later the same year. They paid a total of 15,000 yuan ($1,974) for it, including a lump sum management fee.

Huang spends her days playing cards or chess with other retired neighbors. She still complains - about rising grocery prices, the heating bill (1,080 yuan or $142 for the six-month long winter) and medical charges, but adds: "I'm truly grateful for this government policy. Without it, I would never be able to afford a decent place."

Wang Yajun, a community officer at Modigou, has witnessed it all. "It's not just a shelter, but an embodiment of hope," she said. There used to be about 100 single men who could not find wives; now 22 of them have married. Before, Modigou was hit by the highest crime rate in the city, now there is virtually no crime. Before, a motor vehicle driving around would be mobbed as neighbors pleaded for help from the riders, who they assumed were in some official capacity. And now they organize campaigns to get rid of such old habits as throwing garbage out on the street.

In Xindihao, another Fushun peng gai quarter of 53 new buildings accommodating 1,500 households, many ground-floor units have been converted to mom-and-pop stores, offering convenience for neighborhood shoppers and a few jobs for owners.

Feng Dongyuan, the outside bride who moved into Modigou last year, revealed that she fell in love with her handsome husband and her dating was not protested by her family.

"They knew he's a great guy." But she admits that it helped that his family were vacating their previous 24 sq meters. Her parents-in-law, who worked at the nearby coal mine, had bought two units, taking up the smaller one and leaving the 56-sq-meter one for the newlyweds. Now, sitting in the immaculately decorated two-bedroom unit and holding her newborn baby in her arms, she could not suppress the feeling of content.

"When my son can walk and is put in a kindergarten, I'll go find a job in a big supermarket. But I'll get some computer training first," she envisioned the future. "As for my son, I want him to grow up healthy and go to a big city where he can expand his knowledge and learn new skills, and then come back to build up his hometown."

Duan Haoze, her 4-month-old son, may never know what his hometown looked like before he was born. He was born right into a new age.

|

(China Daily 06/28/2007 page28)