Nature's skyscrapers

World's highest railroad, fastest train, biggest dam, tallest building. The Middle Kingdom's stellar list of engineering achievements has earned it many doting admirers, though perhaps Mother Nature is not foremost among them. Not only has China's remarkable industrialization drive left scars on her landscapes. It's also pilfered her best designs.

Dust down the copyright handbook and summon the lawyers. It turns out that the towering skyscrapers and apartment blocks of China's modern cities have a precedent in nature that goes back two million years.

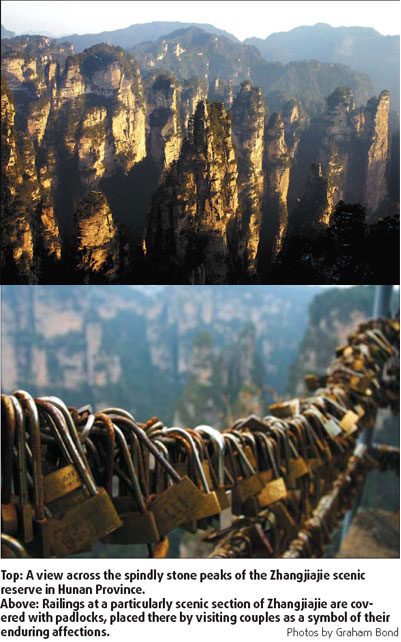

It's to be found at Zhangjiajie in northwest Hunan Province where thousands of sandstone columns rise up precipitously from a deep canyon floor. Each one is a gravity-defying compression of slate; each a masterpiece of shape and form; and each one, utterly unique. There's surely no better looking metropolis on the planet.

The first time I walked around Hong Kong I found myself involuntarily craning my neck towards the heavens and quietly marveling at the manmade peaks of concrete and steel. My first taxi ride on the elevated freeway through Shanghai's high-rise city-center prompted a similar sense of wonderment.

And now, here I was, striding through a remote rural valley in central China, gazing skyward and experiencing that same sense of disbelief. Once again, the same question raced through my mind: how on earth did that happen?

Many geological oddities have the label "unique" thrown at them but Zhangjiajie feels like it might just be able to justify the boast. Those looking for comparisons might point to the Bungle Bungles in Western Australia, or the Pinnacles in the US state of Colorado. Zhangjiajie is greener, wetter and quite simply better endowed than these distant rivals. The UNESCO scientists who gave the site World Heritage listing in 1992 counted 3,100 quartzite towers. Between them are ravines and gorges with streams and waterfalls. Throw a few misty hoops around the peaks and you have a picturesque landscape that is surely unrivalled.

The signs at the entrance whet the appetite for the wonders within by describing the reserve as a "natural oxygen bar", a testament to both its lush forest covering and the state of the air in what is otherwise a heavily populated and relatively industrial region. Indeed, the valley floor is thick with carbon dioxide-gobbling trees and bushes. Some of them are so well-fed that they have been able to climb the peaks and decorate the white stone with flourishes of green.

Zhangjiajie is celebrated for its many endangered plant and animal species. More than 100 species of vertebrates have been listed, including amphibians, reptiles and mammals. A number of these are threatened with global extinction, including the giant salamander, the clouded leopard and the Chinese water deer.

Mass tourism has arrived at Zhangjiajie and sightings of these creatures are now almost unheard of. However, given the spectacular surrounds, even an encounter with the most familiar of creatures can prove a mesmerizing experience.

Walking home from my first day in the park, a gray squirrel with peculiar streaks of red fur bounced along beside me. There was a rustle of twigs as it leapt from rock to rock. The only other sound in the whole of this vast valley was the drip of melting snow and the occasional burst of bird song. We were totally alone.

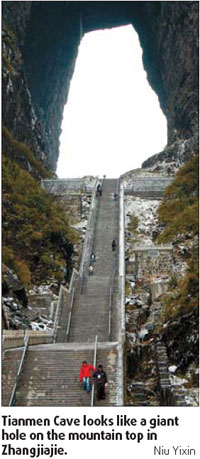

The region known as Zhangjiajie actually comprises three distinct areas, each connected by a series of hiking trails, stairways and sealed roads. To the east is the Suoxi Valley, dominated by a large lake and bordered by the town of Wulingyuan. To the north is Tianzi Mountain, from where it's possible to get spectacular aerial views of the reserve. Zhangjiajie Forest Park, meanwhile, is the largest area and lends its name to the entire scenic reserve.

Connecting the different regions is a 5.7-kilometer-long walkway that cuts a trail along the luxuriant valley floor. This paved path follows the Jinbian River and every so often a gap emerges in the forest canopy, presenting a dizzying view up towards the mountain peaks.

Climbing those peaks is as easy or as difficult as visitors want to make it. There are plenty of stone-step trails, though most of the one million annual tourists make use of the cable cars that ferry visitors to the top of two peaks, Huangshizhai and Tianzi, from where there are stunning views across the forest of stone towers.

There is a third mechanized climbing option that should not be missed. The Bailong Lift is attached by bolt and rivet to a sheer cliff face and is cited in the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest outdoor elevator in the world. Having negotiated a labyrinthine queuing maze, I was ushered into a glass bubble and whisked up 326 meters in just 118 seconds. The views, needless to say, were thrilling.

From the top, it's a short bus ride to join a paved pathway that lines the so-called "Southern Cliff". The immediacy and severity of the drop here makes it testing for anyone who might struggle with heights. Indeed, one of the man-made bridges comprises a wince-inducing grilled walkway through which hikers can peer 300 meters straight down to the valley floor.

A little further on is the Highest Natural Bridge in the World, a 40-meter stone arch which connects the canyon wall with one of the freestanding outcrops.

A little further on is the Highest Natural Bridge in the World, a 40-meter stone arch which connects the canyon wall with one of the freestanding outcrops.

The hills of this part of Hunan are riddled with caves. Huanglong, or Yellow Dragon, cave - just east of Zhangjiajie's most easterly gate - is thought to be one of the 10 largest in China.

The interiors are decorated with spectacular stalagmites while the largest cavern reaches an astonishing 142 meters in height. The abundance of colorful neon means certain parts of the complex resemble a nightclub more than a stately geological marvel. All the same, it's hard not to be impressed.

As with all of China's most spectacular parks, getting the best out of Zhangjiajie involves outsmarting the weather. The peaks look radiant against a clear blue sky, while wispy ribbons of mist often add drama to the backdrop. However, the canyon is all too frequently smothered in low-lying cloud.

Visitors on the wrong end of one of the area's famous pea-soupers should look at things philosophically. Maybe old Mother Nature is just protecting her privacy. And after the plagiarism of the last few decades, who could blame her.

(China Daily 05/31/2007 page19)