The good oil

Zhan Jianju, chairman of the Oil Painting Society of China, does not remember how many art exhibitions he has witnessed over the past decades either as an organizer or a special guest. However the 76-year-old last week finally took center stage at the opening of his first solo exhibition at the National Art Museum of China.

"How time flies! I have grown from an energetic young man to a frail, gray-haired old man. And it is a pity that many of my former teachers and classmates cannot see this solo retrospective show. They are gone forever," says Zhang.

He choked for a moment when delivering the speech, standing before hundreds of visitors, mostly his former classmates, colleagues, fans, and former students including Liu Xiaodong, Yu Hong, Yan Ping, and Chao Ge, popular young artists.

"Zhan is not only an influential oil artist but also a brilliant art educator who can not be ignored by researchers of the 20th century Chinese oil art," said Jin Shangyi, head of Chinese Artists Association, who was a former classmate and colleague of Zhan at the Central Academy of Fine Arts.

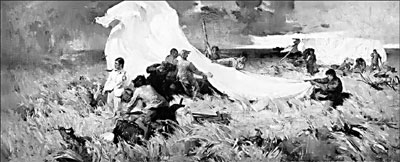

Starting From Scratch, by Zhan Jianjun, oil on canvas, 140 x 348 cm, 1957. File photo |

With 160 selected oil paintings, sketches, colored murals, and time-weathered political posters, the solo exhibition chronicles the veteran artist's life-long artistic pursuit.

"It is during the preparation of this exhibition that I have come to see what voluminous and diverse works I have painted over the past 59 years since I took the path of oil art. It really surprises me," Zhan admits.

According to Pan Gongkai, president of Central Academy of Fine Arts, "Zhan's oil works, created in different historical periods, offer people a glimpse into both China's dramatic social changes and ups and downs in the development of Chinese oil painting."

However, Zhan's early interest was not in oil art but Chinese ink painting. Born in 1931 in Shenyang, in Northeast China's Liaoning Province, the Manchu ethnic artist moved later to Beijing with his family. He was first introduced to Chinese ink art in the early 1940s during his primary and middle school years, becoming a key member of the Snow Reed Painting Society. In his spare time, he did some gongbi (fine-brush) paintings with friends in the society. "I really enjoyed it," the artist said.

His talent soon attracted attention from both his parents and teachers, who encouraged him to enrol at the National Peking School of Art. Founded by master painter Xu Beihong, it later became the Central Academy of Fine Arts. There he began to learn the basics of Western art.

In the early 1950s, Zhan learned more about traditional Chinese ink art from Xu Beihong, Dong Xiwen, Wu Zuoren and other masters. After graduation, Zhan stayed at the academy as a lecturer and continued Chinese ink painting.

Thanks to his academic merits, Zhan became an assistant to master Ye Qianyu who visited the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes and Tibetan communities in Gansu Province. Some of Zhan's imitations of the Mogao Grottoes are included in his solo exhibition.

Despite his strong interest in Chinese ink art, Zhan was advised by his teachers to change direction when Russian artist K M Maksimov (1913-93) taught in China in 1955.

"At first, I was reluctant to put aside my ink brush. But I knew it was a rare opportunity to grasp the techniques of Western paintings. So I took the offer," Zhan said.

"I have benefited a lot as a Chinese oil painter from my cultural roots. Embracing one art genre does not necessarily mean abandoning what you have learned before that."

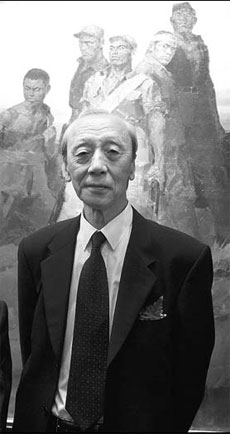

Zhan Jianjun in front of his 1959 painting Five Soldiers on the Langya Mountain displayed at the National Art Museum of China. Jiang Dong |

While most students followed closely in the steps of the Russian artist, Zhan tried to take a path less traveled.

"Zhan is a man of independent thinking. As early as his apprenticeship under the Russian oil guru, he tried to forge his own voice. And he was labelled 'the student whose painting style is the most distant from that of his Russian teacher'," said Zhong Han, a famed oil artist and Zhan's former classmate.

Zhan won national reputation in 1957 with the award-winning Starting From Scratch, which features a group of young geological surveyors trying to set up a tent against chilling winds in the wilderness.

"I still remember his debut work - its imposing composition, the bold, contrasting coloring, the forceful strokes and lines, the fluttering tarpaulins in the wind, they all manifest a distinctive style," said Zhang Shizeng, an art historian in Beijing.

Another major work of that period that drew huge critical acclaim was Five Soldiers on the Langya Mountains, a piece commissioned in 1959 by the National Museum of Chinese Revolutionary History, now treasured in the National Museum of China.

"It was a political task. I revised the drafts many times, trying hard to bring to life the heroic soldiers who chose to leap off the cliffs instead of surrendering to enemies in the 1940s," Zhan said.

He worked out the right scenario, the moment they used their last bullets and confronted the enemies with bare fists at the peak.

Rendered with cool-color tones and a dramatic composition in accordance with the law of Golden Section, Zhan, then aged in his 20s, successfully re-created the stirring and solemn moment, making the soldiers appear to be a lofty mountain peak of flesh and blood.

"The work impresses the viewers not only for its content but also its well-crafted visual strength. As I feel it, the visual quality even surpasses its revolutionary content," commented Shui Tianzhong, an art historian and research fellow with National Art Museum of China.

"The painting is a telling evidence to Zhan's ceaseless efforts to strike a balance between political and social needs and artistic perfection."

The work became one of the best-known political posters during the 1950s and 1960s.

In the 1960s, Zhan and many of his contemporaries were thrown into the whirlpool of the political movements. From mid-1960s to 1977, Zhan worked as a farmer in Hebei Province.

"A lot of my early oil paintings and sketches, labelled 'black paintings' by those who were unhappy with my rebellious and innovative approaches, were burnt or got lost. I miss them so much," Zhan recalled.

But he never lost faith in what he believed to be good art.

"Under various social and political circumstances, I have always tried to paint works that are both 'politically correct' and 'acceptable' according to my own criteria of quality art," Zhan said at a press conference before the exhibition.

In the late 1970s when Chinese society took a dramatic turn for opening up and reforms, Zhan's passion for oil art was once again rekindled.

"I am deeply moved by his passionate pursuit of a distinctive artistic style despite setbacks in his personal life," said Fan Di'an, director of National Art Museum of China.

Fan finds that Zhan's artistic style has evolved with time. In his works over the recent two decades, Zhan has borrowed new techniques and ideas from Western art to enrich his oil art, Fan observed, citing Zhan's Song of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and Looking Back.

The former was the fruit of Zhan's visits to Tibetan communities in the early 1980s in Tibet, Sichuan, Qinghai and Gansu. While many other Chinese oil artists depicted the beautiful but harsh natural conditions in these places, Zhan portrays a pretty and happy Tibetan girl, symbolic of the optimism and vitality of Tibetan people who prevail in the highlands and enchant the whole world with their splendid cultures, explained Fan.

The work impressed Fan with its bold but appropriate use of red coloring.

The red color was overused for oil paintings and political posters during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). Artists avoided it in the late 1970s and early 1980s. "Zhan used it freely in his paintings and has achieved unexpected visual effect. In his works, the color red virtually got the new meaning of the awakening vitality in Chinese society," Fan said.

In Looking Back, Zhan created a gorgeous scene of the Great Wall, winning critical accolades for its novel composition, striking colors and profound cultural relevance.

It easily reminds viewers of the tumultuous history of China, imbued with blood, fire, pride and humiliation, Fan says.

"At 76, I still feel that I can paint and learn some new tricks," Zhan said. "Painting in my studio near Wangfujing Street, which is small and shabby, has always been my happiest moments."

The oil painter has formed the habit of listening to music while sweating over his works. His musical taste ranges from Peking Opera, Jingyun Dagu (story-telling accompanied by drum beats), to Beethoven and Mozart.

Zhan's love of music has enriched his oil art, said Sun Meilan, a veteran oil painter and art critic in Beijing. "From Zhan's oil paintings, I can always feel the rhythms in the visual presentations."

Similar to his affinity to classic and folk music, Zhan prefers to paint in a somewhat traditional style. "Traditional art is by no means inferior to genres in vogue which would some day become part of tradition."

To paint in an "old-fashioned way" or to take a vanguard stance is a matter of choice; what really matters is the artistry each individual artist can achieve and the aesthetic values he or she upholds, he claimed.

Zhan's solo exhibition runs through May 31 at the National Art Museum of China.

(China Daily 05/29/2007 page20)