Spinning a web of deceit

Few people had heard of Ai Qingqing prior to October 15, 2006, when she announced online she would trade a paperclip for a house within 100 days. "I have no money, but I heard about a young Canadian guy who traded a paperclip for a two-storey house. I want to achieve the same kind of miracle in 100 days. Will you help me realize my dream?" her posting read.

Few people had heard of Ai Qingqing prior to October 15, 2006, when she announced online she would trade a paperclip for a house within 100 days. "I have no money, but I heard about a young Canadian guy who traded a paperclip for a two-storey house. I want to achieve the same kind of miracle in 100 days. Will you help me realize my dream?" her posting read.

People soon began to react. More than 1,000 people said they would like to exchange things with Ai. As photos and cellphones, old wine and jade bangles were tossed into the ring, Ai started trading and the value of the articles she received started to grow... and grow... and grow.

Another Internet "miracle" was being born in front of people's astonished eyes.

TV stations and newspapers began to enthusiastically follow the website "miracle" story. Millions of netizens, TV viewers and readers tuned in to track the latest developments.

But, as we all know, things are not always what they seem. It turned out that Ai's spontaneity had been carefully scripted by an invisible partner. The trading ended on January 23 this year, when Ai signed a contract with a record company to become a singer and broke up with the man who was the brains behind the operation.

Yang Xiuyu, nicknamed Li Er, has revealed he masterminded the whole thing, not just the idea of copying the Canadian miracle but every step along the trading route.

He wrote the blog and chatted with netizens using the name Ai Qingqing. In real life Ai Qingqing was Wang Xiaoguang, just an actress in the drama produced and directed by Yang.

The 34-year-old discovered the money-making potential of Internet advertising and promotion four years ago when he was working in a Shanghai-based foreign company and surfing on the Internet to kill time like many other white-collared workers.

He said he planned to act as Wang's manager when Wang became famous with his help.

"I could have earned more than a million yuan (about $130,000) from this operation," Yang boasted.

"More than 30 media covered the bartering. Those companies should really have spent more than 5 million yuan for the coverage we gave them," Yang said.

Companies and small businesses including a bar, a jewelry company, a wine producer and a publishing company clamored to provide things for Wang to barter.

Yang said several other companies had called to offer their products but were turned down because the things were "not suitable for the drama".

After splitting from his "actress", Yang's profit turned out to be considerably less than he had hoped. But the operation was nevertheless a lucrative affair, netting him a six-digit profit. "I should have signed a formal contract with her. I'll do that next time," Yang said.

He is proud of his creativity in what was his debut on the "Internet promotion stage".

Before establishing his own studio, Yang worked for another cyberworld promoter, Yang Jun, the driving force behind cyber star "Tian Xian Mei Mei" or "Fairy Girl".

The "Fairy Girl", from the Qiang ethnic group, allegedly lived in a remote village in Southwest China's Sichuan Province. She was promoted as a pure beauty, who had never known the outside world. In reality, she had been a professional dancer in a local ensemble.

After becoming famous, she was chosen by Sony Ericsson to promote its new mobile phone models.

Being no longer able to get on with his former boss, Yang Xiuyu left and set up his own studio last year. In an era of grassroots entertainment, he looks for attractive cyberspace projects that everybody can take part in, such as the "paperclip for house event".

"These events entertain people and give companies an opportunity to promote their products, and often a cyber star can be created as a by-product," Yang said.

According to official statistics, China had 137 million Internet users by the end of 2006 and the country's online population will hit 200 million by 2010. The cyberworld has become a crucial space for enterprises to promote their products and also for gold diggers, such as Ai Qingqing or the "Fairy Girl".

If the Internet events become big enough, they inevitably attract coverage from traditional media.

Jin Lingyun, a senior editor with the Beijing Times, which covered the "paperclip for house event" along with many other media, including China Central Television (CCTV) and Hong Kong-based Phoenix Satellite Television, said Internet surfing had become an integral part of journalism.

"But when we choose news from the Internet, our rules state that the event must really have happened and the identities of the main figures should be clear," Jin said.

He initially doubted the authenticity of the "paperclip for house event", but many other media had already started to run stories about it.

"If we hadn't reported it while our competitors were doing so, we would have lost readers," Jin said.

In the end, the media competed with each other to establish Ai's fame and later discovered they had been hoodwinked. "What happened is going to harm our newspaper's reputation even if, in the end, we did help readers realize that the whole thing was a con," Jin said.

Jin said when he and his colleagues reviewed the episode, they realized they failed to follow their own rules.

"We did not clarify the identities of the people who exchanged things with the girl," Jin said.

He said that time pressures made it difficult for his news team to check people one by one.

Chen Changfeng, a professor with the Peking University School of Journalism and Communication, said the episode revealed fierce market competition. "The media need advertising revenue and to attract advertisers they must have sufficient readers which means they are always on the lookout for eye-catching news. Cyber promoters capitalize on this," she said.

She said earlier cyber stars, such as "Sister Lotus", the lip synching boys and "Little Fatty", some of whom achieved world fame, were all boosted by different teams of cyber promoters.

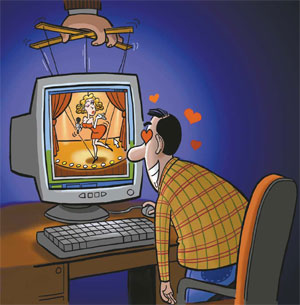

"Behind the cyber stars are clever hands able to manipulate the market, lure common people with dreams of fame, tempt advertisers into promoting their clients and seduce the media into gullibility," Chen said.

She said the media should establish general rules of self-discipline and stick to professional journalism.

Jin Lingyun believes all the traditional media will be much more careful in the future in dealing with Internet news.

But Yang Xiuyu was unrepentant. He said he would continue to target the Internet market. "The traditional media will get trapped again," he grinned.

"You know, anyone can become a promoter and create a story on the Internet," he said.

(China Daily 04/17/2007 page18)