Tapping into the roots

Shanghai Library holds |

The resources have given new energy to some people who thought their past was dust such as Lu Ji, a Jiangsu native, who admits to destroying his family genealogy with his own hands during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). The retiree and his wife found more than 1,500 references to his clan at the library, where they spent a day busy photocopying, photographing and taking notes.

He looks forward to finding even more clues in the online catalogue.

Initiated in 2001, this comprehensive virtual warehouse of Chinese ancestral information

A woman worker tries to fix a document in the conservation workshop of the Shanghai Library. It’s a lengthy |

Users may explore their family trees by typing in their surnames, names of grandparents and great-grandparents, or even places of habitation. Some may be lucky enough to find ancestors going back nearly 1,000 years.

Chinese interest in genealogy itself dates back thousands of years.

The practice of recording family trees began during the Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century - 256 BC) and became popular in the Han Dynasty (206 BC - AD 220).

A Chinese genealogical chart generally shows not only family proliferation over the generations, but also main events and important figures of that family as time passes. To basic entries listing names and dates of birth, personal details would be added in later years for those with accomplishments in academics, politics or business. The record would show, for instance, if someone passed the imperial examinations at the country level.

Traditionally, the main purpose for compiling a genealogy was to maintain good relationships within a clan, to identify individuals with special needs who required support, to ensure proper benefits went to clan members, and to easily sort out family disagreements should they arise.

Not surprisingly, genealogies excluded women's personal information until the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and the subsequent Republic of China (1912-49), when women's social status improved. Even then, only women considered "chaste" were listed.

The wealth clans those of the Chen, Hu and Bao, for instance updated their genealogical charts every 20 years. Less distinguished families were not supposed to go more than four generations without updating.

Historians estimate the existence of more than 50,000 separate Chinese genealogies, but not all can be recovered, since emigration dispersed about a third overseas.

The upkeep of genealogy further declined during China's continuing civil wars and in the "cultural revolution", when the practice was criticized as feudal and volumes of irretrievable records were thrown into the fire.

Interest in family roots was rekindled during the 1980s as the country opened up and preserving tradition became an important corollary to building a modern society.

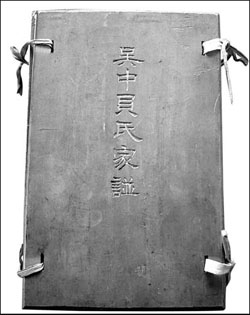

Wuzhong Bei Family’s |

The Shanghai Library holds the largest collection of original Chinese genealogies, some 14,500 family histories and 100,000 volumes in all thanks mainly to Gu Tinglong, its former director, who traveled widely to salvage genealogies from papermaking factories planning to pulp valuable documents mistaken for trash. The earliest genealogy the library possesses is Xianyuanleipu, tracing a family over more than 1,000 years. The most elaborate one, Taiyuan Wang Family's Genealogy, was written in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Other genealogies record roots and offshoots for famous Chinese public figures, from Confucius to the early 20th-century great writer Lu Xun and the early president of the People's Republic Liu Shaoqi.

The computer database includes more than 600 different surnames, with Chen, Zhang, Wang, Li, Liu and Wu being the most prolific.

The majority of genealogies that have survived are from southern China, "because society in the southern region was more stable than in the north, which was always affected by wars," explained Gu Yan, a genealogy researcher at the library. "Besides, people in the south had a long tradition of keeping genealogies and putting every effort into preserving them," she added. A crew of eight or so is working to transfer the original genealogies from storage to cyberspace.

Some remove binding strings and unpack the yellowing documents to be photographed; others consult piles of books and other references as they proof the documents; still others add the information to the online database.

Some records are too fragile to handle and must be sent to a conservation workshop, where half a dozen experienced women workers use needles and tweezers to separate papers, brush pages with special glue and reinforce them with rice paper, in a lengthy process requiring meticulous work.

Gu Yan said the hardest part of the computerization project was bringing all the results together. With more than 1,000 people having been involved in various stages of the project so far, "it requires unity at the final stage," she said. "More information, including that for ancestors who moved to new places and records for Chinese public figures, will be added to the general catalogue."

News of the growing online compilation already has prompted some families to donate private records to the library. Newly-compiled genealogies also are welcome, with more than 3,200 of these having arrived in the past two years.

A decade ago, the library opened a genealogy reading-room to meet the growing interest in family roots, and more 5,000 visitors use the facility each year.

"I don't think senior citizens are the only ones interested in genealogy," Lu remarked. "Most young people focus on their work and don't have time to think about it, but eventually their interest in the past will emerge. The unbreakable tie to roots exists for everyone, and it is good fun to find out how similar we are to our ancestors, and how they too struggled in life, even though we live in vastly different times."

(China Daily 04/03/2007 page20)