Gifts of hope and glory

Illustrations of Her Majesty's Palace at Brighton in the early 1800s. The picture shows the banqueting room at Brighton Pavilion. The Chinese dragon is a repeated motif and the walls were painted with groups of larger-than-life Chinese figures, reflecting the influence of Chinese culture. |

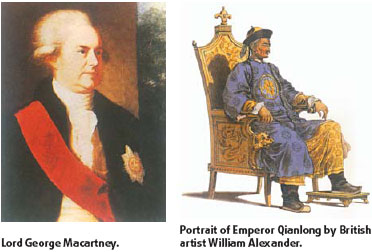

Qing Dynasty emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) had agreed to meet Lord George Macartney, who was passing on an important message from his ruler King George III. Britain wanted to form official relations with the Middle Kingdom and offered gifts showing off the best of British technology and culture. The emperor was offered guns, instruments of astronomy, telescopes, and ornately decorated clocks.

The time was 1793 and the 100-member British delegation included scientists, artists, scholars, guards, valets and Chinese language teachers. The group was paraded through the streets of Beijing with great pomp and ceremony. Qing royal guards, with the Chinese character "courage" written on their uniforms, marched the British tourists through the capital. Thousands of local people rushed to the roadside to see the spectacular and wonder at the strangers who had sailed from halfway around the world.

Both nations exchanged gifts. However, Qianlong told Macartney China had no need for official relations with Britain, or any other nation for that matter, and sent the delegation on their way.

But what were the gifts exchanged on that fateful day?

Britain Meets the World: 1714-1830 features more than 100 relics in the collection of the British Museum and also 10 gifts from King George III to the Chinese emperor in the collection of the Palace Museum.

Left:Firelock presented by Lord Macartney. |

Zheng Xinmiao, director of the Palace Museum and China's vice-minister of culture, hoped "visitors will be attracted to other cultures and appreciate the contribution of different cultures to the development of the world's civilization."

To old Britain, the Chinese empire was the inspiration of the Enlightenment the prelude to the Industrial Revolution that made Britain the world's great power in the late 18th century. To today's Chinese, the Britain of two centuries ago was similar to that of the current economic boom happening in China now.

According to McGregor, the 18th-century British view of Chinese imperial magnificence was shaped by European perceptions of the distant land few had visited.

According to McGregor, the 18th-century British view of Chinese imperial magnificence was shaped by European perceptions of the distant land few had visited.

"Philosophers in Europe had long held up the Confucian ideal as a model of good government," he said. "Gardeners across Europe had created Chinese gardens with pagodas and exotic plants. Traders braved months at sea in fragile ships to bring back Chinese silks, porcelains, and above all tea that essential beverage that became the national drink of Britain."

Qian Chengdan, the Peking University history professor and chief consultant to the popular China Central Television documentary The Rise of Great Powers, wrote in the preface to the exhibition catalogue. He said China is now meeting the world in a similar way Britain did centuries ago and the two countries are now enjoying a friendly relationship after China's 19th-century period of humiliation and misery became history.

The 116-year-period of British exploration has been divided into four parts in the exhibition: "Britain and Europe," "Britain, the Middle East and South Asia," "Britain and Africa, America and the Pacific" and "Britain and China."

Reflecting the economic takeoff and cultural expansion, the first part of the exhibition features landscape paintings in the 18th century, currencies and financial documents, and artworks bought from Europe. The latter include masterpieces from Raphael, Michelangelo and Da Vinci.

The second part of the show displays the British interests in eastern part of the Mediterranean, which was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from its capital in Istanbul.

The highlight in the third part of the exhibition is collectables from Captain James Cook after visiting New Zealand and discovering the east coast of Australia in 1770.

Objects in the fourth part the exhibition suggested how 18th-century Britons perceived China. They include three books on China that served as major sources of information, Chinese works of art collected in the period, studies of Chinese plants, and examples of British chinoiserie inspired by Chinese ceramics.

The most important exhibits in this part are paintings recording the Macartney mission, which arrived in Beijing. William Alexander, the artist, was then the official draughtsman to the embassy, and spent time with the royal families at the Old Summer Palace and the Forbidden City. "Alexander would have been delighted if he had known that some of his watercolours are now shown in the Palace," said MacGregor. "In a personal way the British Museum's engagement with the Forbidden City began 200 years ago."

The exhibition will last three months. The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation in Hong Kong provided the sponsorship, and China's State-owned enterprises like the Air China paid for transportation.

(China Daily 03/16/2007 page18)