Worshipping birds of prey

Zhao Mingzhe lets a falcon fly during a training session in Northeast China's Jilin Province. |

"A good falconer must seize the right time to pull the string when the big bird lands into the trap to catch the coy bird," said Zhao Mingzhe, a farmer of Manchu minority in Northeast China's Jilin Province.

"I learned most of the knowledge and skills about falconry from my grandpa and my father. But I have also developed my own ideas and methods."

In mid-October, when the temperature drops to bone-chilling, the 59-year-old Zhao rises early and hides himself in a warehouse, preparing for his trip to the eagle-trapping grounds on the mountains at least 30 kilometers away from the Yulou Village.

After a hasty breakfast, Zhao and his son Zhao Jifeng hit the mountain paths against the freezing wind before sunrise in search of a few new winged companions.

A good falcon is a useful partner for Manchurian hunters. |

Eagle Town

The Yulou Village, situated at the lower reaches of the Songhua River, is home to some 300 Manchurian families. It is about 50 kilometers away from the city of Jilin and perched at the lower reaches of the Songhua River.

The village has been nicknamed the "Eagle Town" by locals for its unique location and land formation which attract a wealth of wild life including falcons and vultures of at least 15 species.

For centuries, Nuzhen, or Nuchen, an ancient ethnic tribe in China (ancestors of today's Manchu minority), engaged in both falconry and fishing in the areas near the Songhua River and Changbai Mountains in Jilin.

In 1613, the village got the name Yulou, literally "fishing equipment depository", from Nurhaci (1558-1626), founder of the Manchu-ruling Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

It became a major supplier of falcons, wild geese and swans for the royal members and

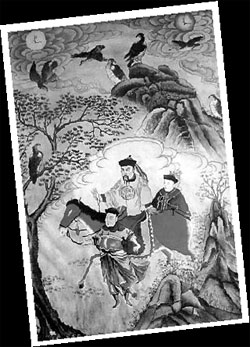

A painting treasured by Zhao Mingzhe shows Qing Dynasty officials hunting with falcons. |

Three families were forced to capture eagles, breed them and then present them to the Qing Court. The falconers were also required to make robes with swansdowns stripped from the swans captured with eagles.

"If the tasks were not fulfilled, the falconers and their family members would be punished or even killed," wrote Cao Baoming, 58, in his newly published book The Last Manchu Falconer.

In ancient times, the folk tradition of catching, breeding and taming the falcons for hunting missions was a popular practice among a large number of ethnic groups across China.

But most of these old traditions have disappeared over the past century or so, said Cao.

As a folk culture scholar, Cao discovered that the falcon training traditions of the ancient Manchu tribes are still alive at the Yulou Village, at the center of an area known as Wula during the Qing Dynasty.

The Manchu style falconry is closely associated with Shamanism, Cao said. And in today's Yulou Village and neighboring villages, many people still practice Shamanistic dances.

Between 2004 and 2006, Cao did interviews with Zhao, watching the veteran falcon tamer using the skills of his ancestors. According to Cao, it was not until the mid-19th century that Manchu falconers gained their freedom and practiced falconry solely for their own livelihood.

Zhao, whose Manchu name is Yiergenjueluo, is believed to be the 12th-generation descendant of Hulanhada, a valiant general under the leadership of Nurhaci.

His ancestor Bagongsheng, the son of Hulanhada, was one of the three generals who, obeying an imperial decree, settled down, got married and devoted their lives to falconry for the emperors of the Qing Court in 1657 at Wula (which is known today as the city of Jilin).

The two other families, surnamed Xi and Luo, still live in the same village with the Zhaos.

Villagers from at least 40 households from the three big families, including Xi Kun, a 98-year-old farmer, have a good command of the theory behind Manchu style falconry. But most of them have given up falconry completely.

The older ones now concentrate on farming while the younger villagers, including Zhao's elder son Zhao Jianguo, have gone to the big cities to work as migrant workers.

Only Zhao Mingzhe and his younger son Zhao Jifeng are still enthusiastic about capturing and training the eagles for hunting in the tough winter days.

The annual per capita income from farming is less than 1,000 yuan ($130) in his village, Zhou said. "Nowadays, we earn a living mainly by growing corns."

Dying tradition

In the early 20th century, the lush forests around the Yulou village were destroyed by wars.

Industrial pollution of waterways and the agricultural use of chemical pesticides, over-logging and excessive reclamation of the mountainous areas over the past few decades took further tolls on the birds of prey.

As a result, "the cultural heritage from our ancestors has been put on the verge of distinction," the veteran falconer said bitterly.

"My father began learning how to catch and tame a falcon at 7. So did I," recalled Zhao.

It took Zhou at least six years to completely grasp the skills for breeding a falcon, from his grandfather Zhao Yinglu and father Zhao Wenzhou. Traditionally, the falconers are led by a Shaman when they go capturing the eagles.

The younger falconers would learn from the Shaman how to sing the Eagle Songs, find food in the wild, make traps, identify different types of eagles, and guard themselves from volcano, earthquake, wild fire, snowstorm, torrential rains, and dangerous animals and insects, Zhao said.

Before these expeditions, the falconers would pay homage to the goddess of eagles at the Eagle Goddess temples.

"Every time I went to the mountains to set the eagle-traps, I would kneel down before the trap and pray for the help of the eagle-goddess who would allow us to catch the eagles and then train them for hunting," Zhao said.

Besides the eagles, Zhao also trained dogs to help him hunt for hares, snakes, foxes, wild fowls and river deer.

"Sometimes, you may encounter dangers such as attacks from wolves," said Zhao, adding that he once managed a narrow escape from an experienced wolf.

Throughout autumn and winter, Zhao devoted most of his time to training the eagles, leaving his wife, Zheng Xiuzhen, with all the family chores.

Even worse, training the eagles is also expensive. The two eagles Zhao is currently breeding eat at least one kilogram of meat a day.

"Now, I have come to understand that my husband, who is very stubborn, thinks it sacred to carry out his ancestors' traditions," said the 54-year-old Zheng.

With more than 40 years experience, Zhao was declared a "Master of the Manchu-style falconry" by the Chinese Folk Artists Association under the All China Federation of Literary and Arts Circles last November in Beijing.

In a few weeks, Zhao will bid farewell to the eagles he has trained over the past months.

Ancient Manchu custom mandates that, after months in captivity, an eagle must be released to breed in the wild in the second month of the Lunar New Year.

"We must observe this rule and begin a new round of eagle trapping, training and hunting in the coming autumn," Zhao explained.

(China Daily 03/15/2007 page20)