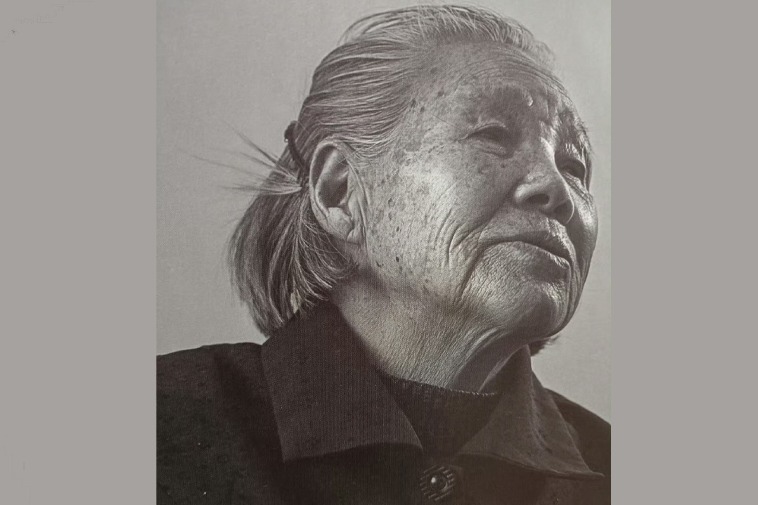

Finding dignity and peace at the end of life

As nation's population ages, cultural taboo of hospice care slowly lifted

A path forward

As China grapples with an aging population and a rising demand for end-of-life care, the country must continue to expand hospice services while addressing systemic and cultural barriers.

Han Qide, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has long championed the development of palliative care in China. He identifies a significant cognitive barrier: the prevailing mindset that insists, "Even with a one-in-ten-thousand chance, we must try to save the patient in the ICU."

Gao Huatian, a professor at Sichuan University's West China Hospital, highlighted a common scenario: terminally ill patients sent to ICUs, their bodies connected to tubes and machines in a desperate bid to prolong life. While intended to fulfill filial duties or uphold a doctor's mission, such measures often cause immense suffering.

Globally, 136 countries and regions have established palliative care institutions, with 20 incorporating palliative care into their social health insurance systems. Foundational and continuing medical education, as well as team development, have steadily advanced in these nations.

In recent years, China has shown increasing support for palliative care. The Healthy China 2030 blueprint promotes integrated health and eldercare services, including inpatient treatment, rehabilitation, daily living assistance, and palliative care. In 2020, palliative care was formally included in the Basic Healthcare and Health Promotion Law.

In 2022, Shenzhen became the first city in China to pass legislation allowing terminally ill patients to decline excessive lifesaving treatments, safeguarding their right to a dignified death. The city's revised medical regulation stipulates that medical agencies must respect a patient's living will regarding traumatic rescues, life-supporting machines, or primary disease treatments at the end of life.

For some, the journey into hospice care begins with small, personal steps. Zhang Xuemei first encountered the concept of hospice care during a charity walk in 2019. Inspired, the then-thirtysomething volunteered at institutions providing end-of-life services.

By 2021, Zhang had become a full-time social worker at a hospice ward in Beijing's Tongzhou district affiliated with Luhe Hospital. Her day begins with morning meetings, where doctors and nurses exchange updates on patients and plan their care. Zhang has built close relationships with each patient in the ward.

"We're here to help patients live as well as possible until they die — and to ensure they die with dignity," Zhang said.

- What's next in AI development? A tech pro's lens

- Beijing mandates helmets for e-bike users, bans scooters

- Judicial guideline streamlines maritime dispute resolution nationwide

- China rolls out festive campaign to boost sustainable agricultural consumption

- China set to establish early pregnancy clinics across 10k hospitals

- Cold front coats Guizhou mountains in rime