More changes expected for HK's 'social contract'

Clear signs are emerging that Hong Kong's essential "social contract" is undergoing a degree of renovation. Moreover, this process looks set to continue. Before examining why this is so, we need to consider the meaning of this expression.

"Social contract" is a term dating to the 17th century work of English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes. Its scope was made more explicit in the 18th century by English philosopher John Locke and Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Briefly, it describes the circumscribed but protective and usually mutually accepted forms of interaction among individuals and groups within their social environment.

Modern political philosophers give the term a particular meaning: an unwritten agreement regarding rights and responsibilities shared between a state and its citizens.

Since the new Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government took office on July 1, many articles have appeared urging various changes in how the government should tackle a range of crucial livelihood issues that are of specific concern to Hong Kong's very large low-income population.

The most important way that successive Hong Kong governments have assisted the vast grassroots sector has been through the provision of secure, small public rental housing on a scale seen in few other major developed cities. But the demand for public rental housing still greatly exceeds supply, with the result that an estimated 226,000 residents, including many children, still live in tiny, subdivided units, and the waiting list for public rental housing has stretched to around six years.

Recommendations for Hong Kong to work much harder on resolving this problem have intensified. Accompanying these calls are heartfelt exhortations to tackle shortfalls in, for example, healthcare, eldercare, child care, education and career prospects for young adults.

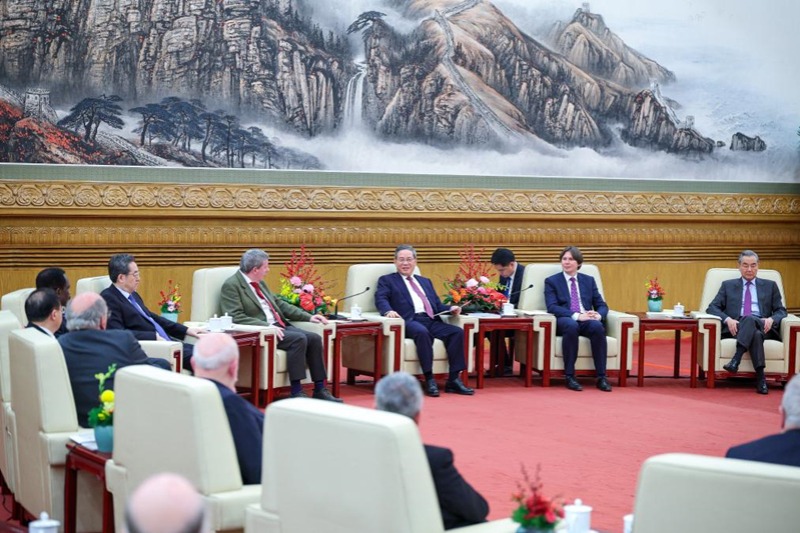

In mid-July, Lau Siu-kai, a professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, spelled out his understanding of the decisive speech that President Xi Jinping gave in Hong Kong on July 1. Lau said Xi's speech signaled that the HKSAR government needed "to substantially change its political mindset "so that the new-term government could "live up to what the people expect of it".

Lau said that the doctrines of "laissez faire, positive noninterventionism or small government-big market, so glorified in the past, should no longer be followed". He concluded that "a more active and people-oriented HKSAR government is desperately needed to promote long-term and sustainable economic development and enhance social justice and fairness."

This is a clear articulation, from an influential scholar, of the need for fundamental changes in Hong Kong's previously long-established social contract. But what did that original, evolved social contract look like? In a series of three influential books, published between 2007 and 2018, another scholar, Leo Goodstadt, explained in detail how business and professional leaders in Hong Kong had long enjoyed a remarkable influence over government policy-setting. This pivotal power of influential persuasion dates back to the 19th century and continued, in Goodstadt's view, after 1997.

It is true that Hong Kong's achievements when it operated in accordance with the previously dominant social contract were extraordinary. By some estimates, Hong Kong had a lower per capita GDP than India in 1945, yet less than 40 years later, its per capita GDP exceeded that of the United Kingdom. In addition, the city government did, during that era, make remarkable strides in building basic public rental housing for several million residents-especially after the deadly riots in the 1960s.

But the problem, as Goodstadt emphasized, was always the lack of a full commitment to fair provision of enhanced benefits for the entire population. Many have commented that this sharply experienced disparity was part of the proximate context underlying the insurrection that took hold from mid-2019.

The International Monetary Fund said in June 2020 that the COVID-19 pandemic had generated "a crisis like no other". As the Hong Kong SAR government began to tackle this exceptional emergency, an important shift in the way in which the social contract operated in the SAR became evident. For well over two years, the perceived rights of the huge number of low-income residents in Hong Kong have been prioritized, by persisting with a strategy influenced by the dynamic zero-COVID policy, notwithstanding a powerfully argued case by a number of business and professional leaders to move decisively away from that strategy. This approach, which aimed to protect the extensive, hospital-based service that is of central importance in protecting the health of Hong Kong's broad low-income population, closely followed aspects of COVID-19 policymaking on the Chinese mainland.

One way of taking a measure of this change is to consider whether, given the traditionally elevated level of business and professional influence on government in Hong Kong, the COVID-19 pandemic may have been managed in a measurably different way had it struck two or three decades earlier.

Considering how the government in pre-1997 Hong Kong was long seen to favor the needs of the professional and elite business class-a trend continued after the creation of the Hong Kong SAR-this prioritizing of the needs of the vulnerable, working class in Hong Kong is not, at first glance, what one might expect. Yet it has happened. This points toward a relatively recent, appreciable shift within certain operational precepts governing the social contract in Hong Kong.

Barrington Moore Jr, a US political sociologist, argued in the 1960s that, eventually, certain embedded societal structures influence the primary protocols of a given social contract. Ultimately, this argument holds that operational political regimes are shaped by the social-class structure of a given jurisdiction.

Although it is too early to say that Hong Kong is unmistakably set to confirm these insights, the intensified, influential calls on the new Hong Kong SAR government to focus keenly on enhancing social justice signal that further significant adjustments to Hong Kong's social contract may yet follow.

The author is a visiting professor on the faculty of law at the University of Hong Kong.

- Russia, resort help Jilin locales prosper

- Snow tourism turns Erhe into winter wonderland

- Shanghai airports see single-day passenger flow cross 410,000 passenger trips

- Passenger trips increase as Spring Festival holiday comes to end

- Spring Festival sees 76% jump in international travel

- Shanghai's railway stations to handle 837k passengers on final day of Spring Festival holiday