Clues from an intriguing past

Discoveries suggest ancient civilizations had common features

This year marks the centennial of the discovery of the Yangshao Culture by Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874-1960). The Swedish geologist was the first to take up a spade and break ground in Yangshao, a small village in Central China's Henan province, in 1921, after which the well-known culture is named.

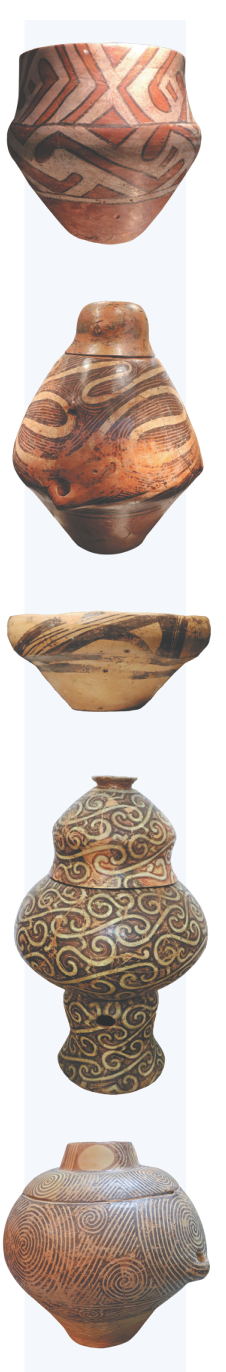

Andersson was fascinated by the Yangshao shards, broken pieces of ceramic material with black painting on them. Oracle bones and bronze ritual vessels looted by antiquity collectors from Yinxu-the ruins of the last capital city of the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC)-in 1899 were the only available clues pointing to the date of the shards known to Andersson.

Therefore, he had to refer to similar examples found in Eastern Europe by German and Ukrainian archaeologists in the early 1900s. These were the Tripolye and Cucuteni cultures, named after the first places where these painted pottery shards were unearthed.

Building upon comparative methodology, archaeology, to some degree, is a discipline of analogy. Comparisons must be made with other findings. The practitioners first observe objects, and then develop their hypothesis to explain why some are similar while others are not.

Based on his knowledge of archaeological discoveries in Europe and Central Asia, Andersson insightfully claimed that the pottery shards found in Yangshao were much earlier than the bronzes found in Yinxu. This was crucial, as it represented the earliest discovered Chinese culture, taking into consideration the time scale of the European counterparts.

After solving the question of when, the question of how naturally surfaced in his mind. The similarities in painted elements and their composition led Andersson to uncritically propose a fanciful theory that the similarities shared by Tripolye and Yangshao painted pottery resulted from the transcontinental transmission from the former to the latter.

Excavations by US geologist Raphael Pumpelly (1837-1923) in Anau (an archaeological site in present-day Turkmenistan) in the early 1900s, along with a large number of painted pottery with analogous motifs, gave Andersson more confidence to assert the cultural connection between Tripolye and Yangshao via Anau.

Chinese civilization is unique and deeply rooted in local cultural contexts. Painting techniques on pottery are not exclusive to any one civilization, but a shared artistic representation among agricultural groups worldwide.

Although Andersson's theory has long been thrown into the trash can, it is still quite tantalizing to explore the similarity in material cultures among two distantly separated regions.

Meanwhile, a thorough understanding of Chinese cultural characteristics cannot be achieved without cross-cultural perspectives. Inspired by the Belt and Road Initiative, Romania, the homeland of the Cucuteni painted pottery, was selected as the first destination for Chinese archaeologists to gain their cross-cultural experience.

Romania, located in Southeast Europe and bound by the Black Sea to the east, has been a crossroads where objects and cultures have been exchanged, and populations have interacted, since prehistoric times. It occupies a strategic position in the so-called "Old Europe".

The peak of prehistoric civilizations in "Old Europe" is represented by the Cucuteni-Tripolye (or Trypillia in Ukraine) Culture, dating back between 7,000 and 5,500 years, spreading across present-day Romania and Ukraine. The site is located about 30 kilometers south of the city of Iasi.

Quite different from most Yangshao Culture sites in the Central Plains, most Cucuteni sites are situated at a much higher elevation. So is the site of Dobrovat in Romania. It is basically located on the top of a hill, overlooking a fertile river valley to the east. A significant distance to water sources apparently does not conform to the common wisdom for selecting a place to dwell.

The puzzle had been hovering until I found a spring in a small gully near the site in 2019. Based on current landscape, I can imagine that the forest must have been much thicker then, when the Cucuteni people settled here. Rich forest resources were used in the construction of their dwellings, daily cooking and pottery firing.

I, along with other Chinese colleagues, was welcomed by a renowned archaeologist couple based in Iasi, professors Magda and Gheorghe Lazarovici-both are in their 70s but still active in fieldwork. They spent their whole career in studying the Cucuteni Culture.

Magda told me that there are thousands of well-preserved archaeological sites like Dobrovat. Yet, only a small number were thoroughly excavated due to the shortage of research funds and qualified archaeologists.

I was shocked when I learned that, over the past decade, they had funded themselves and their excavations from their limited retirement pensions.

The goal of the fieldwork is to reveal a Cucuteni house abandoned around 6,300 years ago. As the top soil, about 20 centimeters thick, was removed, dense red-burned clay chunks were exposed. Most of them have a high degree of sintering and are pretty hard.

It seems to me that the adobe house had been subject to a high temperature lasting for days. Similar houses have also been found in Yangshao Culture and its contemporary neighbors. Yet, consensus has not been reached on the reason why these adobe houses were torched.

The clear-cut boundary invited me to speculate that the four walls of the house might have been intentionally pushed down from outside after a duration of firing.

The interior space of the house was divided into three compartments.

Lots of painted pottery shards were recovered during the excavation. Unfortunately, most of them cannot be pieced together. People might have removed all the utensils when they decided to leave the house and burn it.

Before the excavation at Dobrovat, I also bore the same romantic ideas as Andersson. However, after two months of fieldwork and multiple trips to local museums, I gradually realized that visual similarities on the surface of pottery are superficial and even misleading, because they divert our attention from the key cultural indicators hidden behind these similarities.

The macro historical processes of these prehistoric cultures are more intriguing to me. For example, both cultures emerged and flourished in the transitional era from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age; they developed grain farming as the major strategy of subsistence and economy; and they both underwent waves of cultural expansion, driven by the growth of the agricultural population.

Even thousands of kilometers apart, developmental trajectories of Cucuteni and Yangshao run strikingly parallel to each other, making up the earliest community of fate at both ends of the Eurasian continent. We can only fully appreciate the most unique advantages of the discipline of archaeology, when a subject is being considered in the framework of a community of fate over a long period of time and on a transcontinental scale.

Certainly, answers to these questions still depend on the continuity of fieldwork after international travel restrictions, imposed by COVID-19, are finally lifted.

Wang Kaihao contributed to this story.

Wen Chenghao is a research assistant with Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Today's Top News

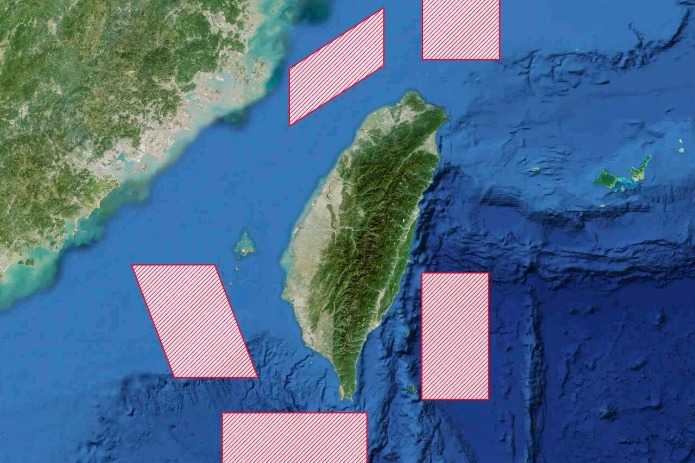

- Drills demonstrate China's resolve to defend sovereignty against external interference

- Trump says 'a lot closer' to Ukraine peace deal following talks with Zelensky

- China pilots L3 vehicles on roads

- PLA conducts 'Justice Mission 2025' drills around Taiwan

- Partnership becomes pressure for Europe

- China bids to cement Cambodian-Thai truce