A delicate thread from history

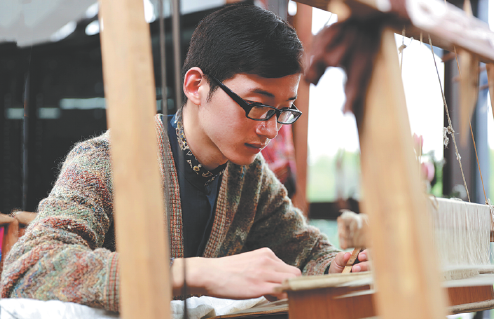

Ancient silk tapestry technique comes back to life at the hands of a determined weaver, Yang Feiyue reports.

Hao Naiqiang is living like a recluse at the foot of a mountain in the countryside near Taihu Lake, of Suzhou city, East China's Jiangsu province.

"It's away from the hustle and bustle of the outside world, better for me to concentrate the mind and explore kesi," says the 32-year-old, originally from North China's Hebei province.

Kesi is silk tapestry with pictorial designs. Its Chinese designation means "cut silk" and it derives from the visual illusion of cutting thread, even some kind of effect of engraved relief, that is created by distinct, unblended areas of color.

The earliest existing kesi products date back to the Tang Dynasty (618-907), but the technique first became widely used during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and it became particularly popular during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

It is one of the very few weaving techniques that cannot be mechanized, and was added to UNESCO's list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2009.

Hao was drawn to kesi in his sophomore year when his professor at Soochow University arranged for his class to tour a private workshop.

He was mesmerized by how a delicate kesi product could come out of a rough "machine"-a tapestry loom that looked just like a pile of logs.

"It was exquisite, just like an engraving," Hao says. "You have to see how the shuttle constantly shifts horizontally and vertically and watch the kesi work come out of the loom to believe it."

For kesi, raw silk is used for vertical threads and colorful boiled-off silk for horizontal threads. The vertical threads are continuous while horizontal ones are not. The colorful threads are weaved to create various patterns. Held against the light, the patterns seem carved or engraved.

"It was simply magical," Hao says.

Kesi had already been etched on Hao's mind, albeit vaguely, when he learned about it by reading A Dream of Red Mansions, a classic Qing Dynasty novel, in his early school years. "In the book, kesi was described as splendid, and was exchanged as gifts among the wealthy, so I imagined that it must have been something extraordinary," he says.

Hao says that he has been fascinated by textile work since before college and he admires the water towns in the south of the country.

Because of this passion, he strived to study the weaving and dyeing art and design major at Soochow University in Suzhou. He was enrolled in 2009 after taking college entrance examinations three times.

"I love learning things which require lots of handwork," he says.

In the third year of college, in 2012, Hao jumped at the opportunity of a three-month internship at a kesi workshop.

In addition to taking care of the regular school requirements, Hao embarked on a two-hour commute by bus to the workshop every day, come rain or shine.

The complexity of kesi saw many of his classmates abandon the craft, but Hao persevered.

"You have to make sure the pattern is smooth and vivid, and the colors are rich," Hao says.

He spent four or five hours a day learning about the craft at the workshop, and by the time the program finished, Hao had grasped all of the necessary skills and had managed to make some simple, small kesi items on his own.

"It was just the beginning, and I still needed a lot of time and practice before I could pull off a decent piece of kesi work," he says.

For the college's graduation design exhibition in 2013, Hao surprised his classmates and professors by making a tea table mat that integrated the kesi technique with decorations of willow branches, while his classmates all resorted to conventional fabrics.

As he sees it, the craft has evolved into a fusion of painting, calligraphy and hand-weaving or embroidering, so he will explore it from those perspectives as well.

In fact, the craft was used for robes, silk panels and scroll-painting covers, as well as for converting exact, whole traditional Chinese paintings into tapestries. Kesi products once made their way to Europe during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), where they were incorporated into cathedral vestments.

To Hao, graduation marked both a new beginning and a new challenge. He has to make a living while continuing to study the craft.

At first, Hao's family and friends tried to persuade him against building a career around kesi, since they considered the craft to be appreciated by such a small number of people that learning it made little commercial sense.

But Hao was determined and, in 2013, got a job at the Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute.

"I was lucky when the institute hired retired kesi experts to teach us young people," Hao says. He adds that he was especially grateful to his tutor Li Ronggen, who imparted comprehensive knowledge about the finer aspects of the craft.

However, while the learning process was smooth, Hao was struggling to make ends meet.

As a probationary employee at the time, he was only drawing a monthly salary of 1,200 yuan ($188), and had barely anything left after paying rent.

Hao had to make handicraft items after work and peddle them at tourist spots at weekends.

"It was hard, but fulfilling," he recalls.

Hao became increasingly recognized by people in the industry, especially with his college design degree and kesi expertise.

But, it didn't take long before he was seeking change.

"I was basically doing what I was told at work," he says. "But I wanted to do something different, something with my own ideas."

In 2015, Hao took the plunge and opened his own art studio.

At first, it gave him great satisfaction to make things his way and receive orders, but setbacks soon followed.

Some customers reneged on a deal, leaving Hao bearing a substantial cost.

However, a lucky break came later, in 2015, when a female student who was studying abroad approached him via his Sina Weibo account and asked him to make a circular fan in a Qing Dynasty style.

He said yes, even though he had never made a fan before.

However, she refused to take the item after Hao finished making it several months later. "She said it was flawed and wasn't good enough, which packed quite a punch," he recalls.

It spurred Hao to seek ways to improve and he decided to base his creations on the book, Here Comes the Gentle Breeze: Qing Court Fans in the Palace Museum Collection.

To ensure exquisite kesi work, Hao was meticulous in tracing the patterns from the book, and went to a colored yarn workshop and his friend's dyehouse to find just the right colors.

The covering of Qing-style fans from the book features kesi, embroidery and elements of color painting, while Hao made the covering of his fans with full kesi craft, and only used embroidery to embellish the frame and handle.

A couple of months later, Hao delivered three Qing-style fans-one featured a phoenix resting in a Chinese parasol tree, another had flowers and birds, while the last depicted a palace and a crane.

The fans were an eye-opener, especially compared with ordinary paper fans. They attracted 500,000 views online after the images were posted in mid-2015, putting Hao on the map.

However, when people beat a path to Hao's door asking for such circular fans, he turned them down.

"I'm not an artisan for circular fans, but of the kesi craft," he explained to them.

Hao went on to explore possibilities of applying the kesi technique to various other contemporary items, creating bags, belts and home furnishings.

In 2016, he teamed up with Sheme, a woman's shoe brand from Chengdu, Sichuan province, and developed refined qipao, or cheongsam, dresses and delicate shoes with kesi elements, which became the center of attention at the 2016 Shanghai Design Week.

People flocked to Hao's workshop to appreciate and learn about the kesi craft as a result.

"I didn't imagine that kesi could be made into costumes, handbags and shoes," says Yuan Zhenhua, who had been working at a kesi plant in Wuxian county, Suzhou city, for more than 30 years.

She has noticed Hao when he used to go to the plant and offered him tips about kesi production.

"My colleagues and I were impressed by how he could make products using the kesi technique at his age," Yuan says.

She has been helping out at Hao's workshop since retiring.

"I hope I can still improve my kesi works and pass on my skills to more apprentices," Yuan says.

Hao and the artisans at his workshop can finish 10 major kesi works a year, and they've been experimenting with applying the craft to other products, such as facial masks, and to the restoration of ancient paintings.

At the moment, Hao spends most of the time sitting before a loom, exploring ways of integrating the ancient kesi technique with other art forms.

In his free time, he plays guzheng, a zither-like traditional Chinese musical instrument, and paints when he feels like taking a break at his rural abode.

"I only go to the city if I have to," he says.

"I'm looking forward to a lot more kesi crossover cooperation and development in a variety of applications in the future."

Today's Top News

- S. Korea's ex-president Yoon sentenced to life in prison on insurrection

- Chinese envoy urges advancing multilateral cooperation at UN committee meeting

- Takaichi officially reelected as Japan PM at Diet

- Xi sends Chinese New Year card in return to friends in US state of Iowa

- Japanese PM Takaichi's cabinet resigns

- Iran not to abandon peaceful nuclear technology