Guarantee leaves many feeling shortchanged

"Rest assured that if you are willing to have a second child you need not worry when the baby is born. I'll help you take care of it."

This reassuring pledge from a mother-in-law will be familiar to almost every young mother in China. But how much faith can anyone have in it? Is it true that after a child is born, the mother can really forget about employing professional child care and hand the baby to the mother-in-law?

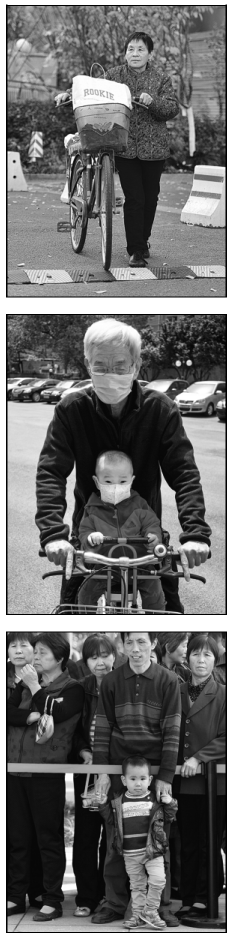

A small number of mothers-in-laws may well prove to be invaluable in the care they offer to their grandchildren, and a recent survey by the internet portal Sohu shows that the maternal grandmother, rather than her paternal counterpart, has gradually become the main force in raising babies, especially for two-child families.

The Chinese language highlights the importance of the differences between paternal and maternal relationships. The differences mean a lot to Chinese and determine the real relationships, near or distant, inside or outside, between relatives. So in Chinese the words for paternal grandmother and maternal grandmother are strictly distinguished in pronunciation and writing: laolao or waipo for maternal grandmother and nainai for paternal grandmother.

Before giving birth to her first baby eight years ago, Liu Qing was a nurse with a heavy workload. Her mother-in-law persuaded her to quit her job so she could focus entirely on having the baby and on her family. Now, she says, she regrets abandoning her nursing career and calls it the result of brainwashing, even though she is now an officer worker in a private company. What really surprised her in all of this was that her mother-in-law broke her promise of full support after the first baby was born, she says.

After a quarrel, the nainai quit for good. Although Liu's husband earns a relatively handsome salary, for the whole family if you want to maintain a healthy income you must have both marital partners working at the same time, especially in the biggest cities. Liu felt very distressed, and finally asked her mother Wang Meiying to help her take care of the baby at home during the day.

Indeed, a popular jocular rhyme on the internet portrays the phenomenon vividly thus: mother born, laolao care, papa busy surfing the internet; laoye (maternal grandfather) circling around the vegetable market; nainai and yeye (paternal grandfather) dropping by with a smile. In the case of every laolao, they are so keen to help take care of the children because they love their daughter.

"The generation gap is a common problem," Liu says."It exists in every family, just as every family has problems, particularly in the mother-in-law/daughter-in-law relationship."

In real life, when the paternal grandmother takes care of the children, if there is a conflict with the mother, sometimes she badmouths the mother in front of the children, or even in front of outsiders.

But if the maternal grandmother takes care of the child, this is unlikely to happen. Laolao is likely not only to take care of the child with gusto, but will usually enjoy a good relationship with the son-in-law, too. To ensure her daughter's marriage is happy she will keep her mouth shut even if she is feeling unhappy about things.

"Another bonus of children brought up by laolao is that they will learn to know to be grateful to their mother more, with laolao keen on educating the children about how difficult it is for his or her mother to give birth," Liu says.

However, Wan Qirong, a senior psychologist at Wuhan University's Renmin Hospital, says the root cause of this situation is a communication problem, not that maternal grandmothers are more likely to raise children better than paternal grandmothers. Accumulation of negative emotions can easily lead to escalation of conflicts and eventually make the whole family unhappy.

Putting pressure on relationships even more is women's traditional role as what researchers call kin keepers who maintain the family social calendar, relationships and traditions. Complex family relationships interwoven with a second child makes it an aggravating issue with more young parents having reservations about having a second child.

At the initial stage of the introduction of the second-child policy in 2016 the number of domestic newborns rose to 17.86 million, the National Bureau of Statistics says. However, this momentum has not continued. The number of newborns in the country fell to 17.23 million in 2017. A clear downward trend was marked in the following years, with the growth rate of the population continuing to fall to the lowest population increase since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, 10.5 per 1,000, with only 14.34 million newborns in 2019.

The government has adopted various policies and incentives aimed at increasing the birth rate and ensuring a more stable population composition including mandatory "cooling-off periods" for divorcing couples. Last May Henan provincial government revised the Regulations on Population and Family Planning with the first paragraph of Article 15 amended as: "A couple (including remarried couples) are encouraged to have two children".

Last year the Proposal on Adjusting Social Family Policy and Addressing Population Development Issues, put forward by the Central Committee of the Democratic League, explored the feasibility of a comprehensive fertility safety system that lasts from birth to the age of 18. In an interview with Xinhua, Huang Xihua, a representative of the National People's Congress, said the Ministry of Finance may consider the distribution of childbirth subsidies. From birth to the age of 6, the State would provide a certain amount in childcare subsidies every month in accordance with the local minimum wage.

However, even with stimulatory policies, more than half of working mothers say they do not want to have a second child, and 40 percent of working mothers are keen on giving birth but are unwilling to go through with the idea, especially in first-tier cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Working mothers were more worried about having a second child and were under greater pressure, a survey on living conditions of working mothers by Zhaopin Recruitment found in 2019. Nearly 85 percent of responding mothers who said they dared not have a baby were mainly worried that the cost of raising a baby would be unaffordable.

Discrimination in the workplace toward potential child-bearing women is another important reason that stops women from giving birth. One such group consists of those who are married and have not given birth. With their opportunities for promotion they are likely to suffer invisible discrimination, and giving birth to a baby, not to mention a second one, will set them back financially and in their careers in terms of time.

Liu Qing, the former nurse, says she hopes time passes quickly, and soon, when the second child reaches primary-school age, she and her mother will both be leading far less stressful lives. However, Liu's mother, exhausted and lonely at times, says she has no regrets about talking her daughter into having the second baby.

"I always hoped to have a bigger family, and my daughter's generation have to bear the heavy burden of taking care of four seniors as the single child in the family. I think with the second-child policy the next generation will have a lighter burden in taking care of the elderly. That surely must be good for everyone."

Today's Top News

- Ukraine says latest peace talks with US, Europe 'productive'

- Economic stability a pillar of China's national security

- Xi taps China's deep wisdom for global good

- New rules aim for platforms' healthy growth

- Chinese web literature grows overseas

- Postgrad exam trend points to thoughtful approach