Bridging the gap between north and south

Experts say a growing economic imbalance between China's northern and southern regions must be resolved as the proposals for the 14th Five-Year Plan emphasize coordinated regional development. Luo Weiteng reports from Hong Kong.

Now a different geoeconomic divide — between north and south — may be overtaking the east-west gap as the primary regional imbalance, and has become a topic of major concern not only in official discourse of Chinese leaders, but also in daily conversations among ordinary people.China has made great strides over the past two decades in bridging the economic gap between the country's landlocked western regions and the richer coastal cities of the east since it launched its ambitious western development strategy in 1999.

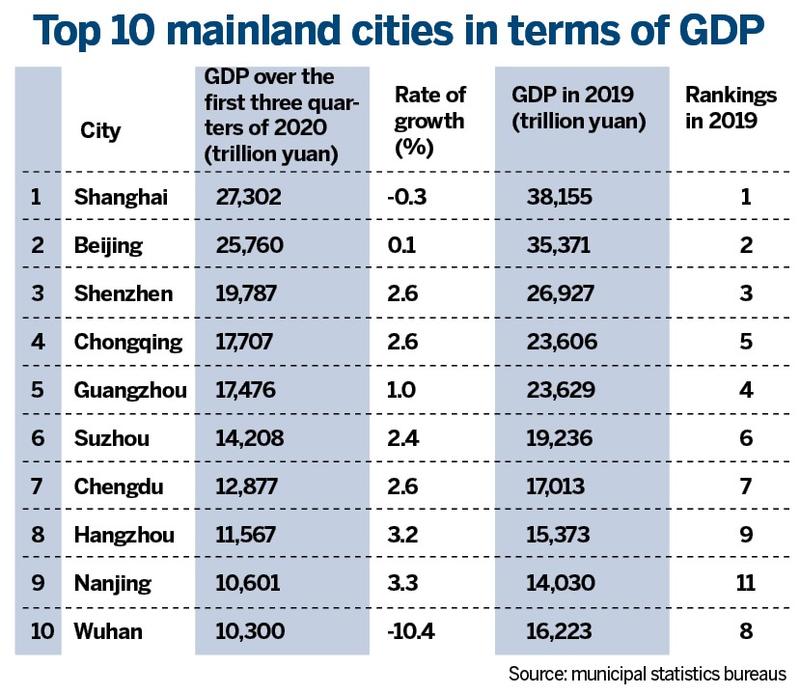

Beijing, China's sprawling capital, is the only city in the country's north still among the mainland's top 10 in terms of economic size over the first three quarters of 2020, government data shows.

Tianjin, one of China's four municipalities under the direct administration of the central government, lost its position in the league table for the first time on record, overtaken by Nanjing, the capital city of eastern China's Jiangsu province.

Even if the top 20 cities on the list are considered, only four in the north managed to join the ranks of the elite club.

Beijing also stands as the only northern city to make the top 10 in terms of comprehensive economic competitiveness, according to the report, jointly released in December by the China Academy of Social Sciences and the United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

Though some may argue that GDP numbers tell little and feed the illusion of growth and happiness, Xiao Jincheng, director of the Institute of Spatial Planning and Regional Economy under the National Development and Reform Commission's Academy of Macroeconomy, said that "the economic disparity between north and south is an indisputable fact and is likely to widen further in the future".

The north's share of China's economic output dropped to 35.4 percent in 2019 from 42.9 percent in 2012, even though the region comprises 15 provincial-level areas, 42 percent of the nation's population and 60 percent of its territory.

At the end of 2019, 13 of 17 Chinese cities with a GDP in excess of 1 trillion yuan (US$154 billion) were in the south. The total number is projected to reach 24 in 2020, with southern cities taking as many as 18 spots.

"While the membership of the '1-trillion-yuan' elite club remains as a privilege for very few mega cities in the north, the coastal provinces in the south are on pace to see city clusters in the making," said Zhu Baoliang, chief economist of the State Information Center under the NDRC, referring to economic powerhouse development plans such as the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area.

This points to more "coordinated regional development" — one of key policy priorities highlighted in the proposals for the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25) — a development path totally different from the outdated one that concentrated the overwhelming majority of resources on very few core cities, at the expense of the future development of surrounding counties and towns, Zhu said.

Balanced development

Geographically, China is split north and south by the Qinling mountain range and the Huai River. Throughout Chinese history, these features have also served to slice the country in two culturally and economically.

To the south lie China's most affluent and dynamic regions, home to most of its innovation hubs and busiest ports. The Pearl River and the Yangtze River deltas, which took the lead to embrace a daring, near-iconoclastic spirit of change when China launched its historic campaign for economic prowess in 1978, stand as a pair of calling cards.

To the north are much of its heavy industry and natural resources, such as coal and oil, which helped keep the nation's factories humming to fuel the economic miracle of recent decades. But the once-mighty industrial heartland now is grappling with a deep-rooted, planned-economy mindset, dwindling resources, and a brain drain that are hindering the north's ability to regain competitiveness.

"Investment should not cross the Shanhai Pass", went the once popular saying among China's investor community, referring to a section of the Great Wall of China that separates the northeast from the rest of the country.

Nowadays, with a hint of mockery and exaggeration, an update of the old saying is often expressed: "Investment should not cross the Yangtze River."

"Such harsh criticism highlights the perils of doing business in the north and illustrates at least partially what is ailing the region today," Xiao said. "We must face the issue squarely."

A single factor never tells the whole story of a condition or situation, and this is true with the widening north-south economic gap, Xiao said. Xiao attributed the relative decline of the north to a cyclical, macro-level economic downturn, weak market demand, and falling commodity prices, which together put a strain on the already-sluggish economy in the north.

He also said the decline is due to the nationwide adjustment of the industrial structure, which makes the region, known for its reliance on natural resources and heavy industries, bear the brunt of overcapacity reduction.

While some might also blame the decline on the all-powerful State-run economy in the north, Xiao pointed out the State-owned businesses should be an advantage, rather than a disadvantage. It is a rigid management system and a closed mind that essentially hinder the region from nurturing an environment friendly to businesses and investors, and will have a far-reaching, if not immediate, impact on its future, Xiao said.

Feng Kui, a researcher at the China Center for Urban Development under the NDRC, said people cannot shy away from the fact that the strategic and policy planning of recent decades on a national level favor the south and gave the coastal provinces the early-mover advantage.

Still, Feng emphasized that the so-called lagging north and thriving south are a natural fit for a story that could be easily played up and attract eyeballs to oversimplify the deep-seated problem of China's regional imbalance.

At the heart of the imbalance lies a high degree of polarization, Feng said.

"This includes both the east-west gap and the south-north divide," Feng said. "It is reflected not only in the rate of growth but also in the level of development. It points to the difference in the aggregate economic output as well as the levels of income per head."

Feng cited the Pearl River Delta as an example. In 2019, the economic size of Guangdong province was equivalent to 1.5 times that of the six provinces and autonomous regions in northwest China combined. However, 70 percent of Guangdong's GDP came from the Pearl River Delta. Meanwhile, the imbalance between both sides of the Pearl River is also too remarkable to ignore.

As the proposals for the 14th Five-Year Plan reinforce the theme of coordinated regional development, a strong focus should be put on more balanced development, not only among different regions of the country, but also among different parts within a region, as well as between the core mega cities and their surrounding counties and towns, Feng said.

- Why China walks on path of peaceful development?

- CPC Guidelines for Governing Xinjiang in the New Era: Practice and Achievements

- Xizang fireworks draw criticism, spur probe

- Dunhuang cultural expo seeks to revive the Silk Road spirit

- J-20 fighter can easily penetrate air-defense networks, designer says

- Xinjiang to build new expressway