|

OPINION> OP-ED CONTRIBUTORS

|

|

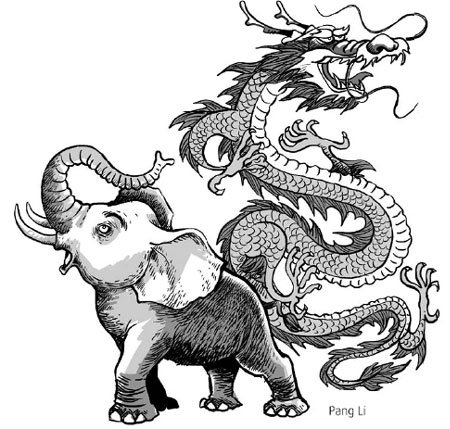

Not the same, but not very different either

By David Dodwell (China Daily)

Updated: 2009-07-21 07:55 Despite the rest of world trying to club China and India together, the two remain at odds rather than agree on most issues. Most Western economists bundle India and China together with Brazil and Russia (BRIC) without pausing to think what they actually have in common. At the Doha Round of WTO talks that have been dragging on for sometime now, China and India are more often than not seen as reflecting the views of a unified developing world. The same is true in case of preparations for the Copenhagen climate change conference in December. To most people looking at Asia from the comforts of Western Europe or the US, the similarities between the countries seem more obvious than their differences. Once upon a time, this probably did not matter.

Despite their huge populations, the impact of the two countries on global diplomacy was minimal for many decades of the 20th century. But today, the international community has already accepted China's importance. Soon the same could become true about India. This makes it all the more important for Western leaders to give priority to understanding the subtleties of the two countries, and they can start by recognizing their similarities and differences. At a personal level, this Western naivety has been frustrating to me. As a young journalist opening the Financial Times (FT) bureau in Hong Kong in 1983, I spent hundreds of hours trying in vain to persuade my seniors at FT headquarters in London that we needed to prioritize our news coverage of China and east Asia, rather than India, where millions of pounds were being poured to print locally, and build a strong local circulation. My arguments that China, rather than India, had the commitment necessary to engage with the global economy, and a quality of economic pragmatism that provided a unique fertile environment for trade and investment, fell on deaf ears. From London's point of view, India was obviously going to emerge first. After all, it had the world's largest stock market in terms of the number of listed companies, a dynamic private sector economy, a free press, and above all, the English language was widely used in the country. Compare that with the stereotypical London view of China as a communist state with a controlled media, state enterprises dominating the economy, and barely a word of English spoken, and you can see why I got nowhere in persuading my bosses to begin publishing in East Asia.

It took another decade before the FT began printing in Hong Kong. Even today, after a quarter of a century of frustration and millions of pounds of wasted investment, the FT still does not print in India. In that same quarter of a century, China has robustly engaged in the global economy, become an exports powerhouse, and attracted about $50 billion in foreign investment every year. It has grown at an average rate of about 10 percent - resulting in a more than 10-fold increase in its per capita GDP. In contrast, India remains on the margins of the world's trading system, it has attracted not a lot more than $50 billion in foreign investment during the entire period, and its average 4 percent annual growth has underpinned a three-fold increase in per capita wealth. While Manmohan Singh, sworn in recently for a second term in office, is cautiously promising to lift India's electricity generation capacity from a past average of about 3,000 MW a year to 10,000 MW, China's power companies have been adding an average of 75,000 MW a year for the better part of the past decade. While China has been building 5,000-8,000 km of new superhighways a year for the past few years, India's leaders talk in terms of hundreds of km a year. China's pragmatism in opening up, allowing foreign companies to set up ventures and having few barriers to consumption of Western products, are in sharp contrast to India's labyrinths of bureaucratic hurdles for firms investing or selling products in the country. Of late, there have been signs of relaxation as India's economy tentatively engages with foreign companies. But people who suggest that India is on a growth track similar to that of China still sound naive. The differences may be many and may go largely unnoticed, but certain similarities have become important for the world. Just as a growing proportion of China's 1.3 billion people are beginning to join the world's consumer class, so too are millions of Indians who until recently lived subsistence lives. It is beginning to dawn on the rest of the world that the emergence of about 2.5 billion new consumers, all set on air conditioners, TV sets, computers, mobile phones and cars, is about to take the world by storm. Working out how we can accommodate the perfectly legitimate aspirations of these people to live more comfortable lives without causing irreversible damage to our environment is without doubt the biggest international challenge of the coming decade. China and India will almost certainly work together closely in addressing how we reach fair outcomes on these challenges. And Western leaders would ignore their arguments at their own peril. The author is chief executive officer of Strategic Access Ltd, Hong Kong. (China Daily 07/21/2009 page9) |