|

OPINION> OP-ED CONTRIBUTORS

|

|

Filter for the Net should not be a strain

By Victor Paul Borg (China Daily)

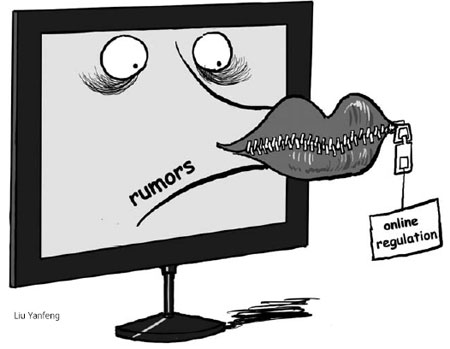

Updated: 2009-07-10 07:53 I have followed the furor over Green Dam software with interest and ambivalence. On the one hand, I can understand the uneasiness people feel at the idea of having to install in their computer a software that blocks a raft of websites and monitors what people do online. Internet surfing is perceived as a private experience, and an individual feels liberated by seeing or speaking about anything online, unshackled by social mores and government vigilance. This notion has become so entrenched that something like Green Dam is unquestionably taken as an intrusion of privacy. Green Dam is designed to directly target websites with violent or pornographic content, but it's apt to widen the discussion about the legitimacy of regulating and monitoring other spheres of content. The Net may be a private individualistic experience, but it has also become a public space. A netizen, even while sitting in the privacy of his home or office, would be interacting with millions of others. The Net is now the largest source of mass communication, and it is becoming the prime source of media entertainment, whether it's reading or watching films or listening to music. It's also used by terrorists, separatists and racists to fan their propaganda and instigate attacks or unrest. It's for these reasons that many countries have set up centralized stations that filter Internet traffic by keywords. This is done to intercept any communication that has the potential to undermine social and political stability, or incite political violence. Such monitoring systems block websites that are considered dangerous for a variety of reasons, too. Yet these centralized stations are being overwhelmed by the sheer volume of data and proliferation of websites. This is leading to the development of dedicated software that filters access at the point of use - on the computer itself. A lot of these out-of-market software are mainly intended to be used as a form of parental guidance. Green Dam is an evolution of such systems.

Given these realities, any country that deems it necessary to manage or control content - whether violent or pornographic, or politically or socially poisonous - in the traditional media (TV and cinema and publications) would feel that the time has come to extend this regulation online. Many countries have in fact been grappling with these issues for years, and their concerns have become more urgent because the Internet's scale has grown to the point that it can affect public and political security. There are romantics and ideologues who take the view that the Internet has led to greater democracy. These people take the growth of blogs as liberation from the constraints of traditional publications, and the Net as a medium that has given a voice to the people who didn't have a voice before. All this sounds fine in theory, but things are greyer in practice. Blogs for example, particularly the ones that deal with non-technological and non-scientific subjects, tend to be inaccurate, uninformed and parochial. A blogger isn't a professional journalist; a blogger doesn't do any professional or extensive research before writing something. Instead, he/she puts his personal impressions or testimony, which are highly colored by his/her prejudices and perceptions, often taking a narrow or parochial perspective and casting it as if it's some larger truth. Bloggers also feel they can level any accusations or allegations without responsibility or consequences because they don't represent a media organization that can be held accountable. Bloggers' greatest flaw is that they often end up writing things that are factually unverified and are not couched in the moderations of professional authorship. For these reasons blogging represents retrogression in the standards of public discourse. So are the so-called social or chat sites and forums, which are a digression in the level of intellectual discourse or flow of ideas. Aside from wasting time prattling online (instead of reading a book, for example), people also tend to behave like a mob in cases where they discuss political or social issues. I'll mention just one recent example. China Daily reported on July 2 about a new program allowing foreigners free entry to 12 major sites in Anyang city, and the netizens vehemently opposed it: 92 percent of the respondents to a Sina.com survey thought that the measure was daft, and 52 percent thought it stemmed from a "weird inclination to treat foreigners better". The issue became the subject of mob ridicule without factual basis. First, the facts are warped (there are tourist sites in China that charge foreigners more than Chinese nationals), and second, there was no serious discussion over these policies. A serious discussion would first establish that as a general principle double-pricing has no place in a modern society, and then it would consider the acceptance of deviations from this principle in cases where specific outcomes are sought temporarily. Before the birth of the Internet, people used to behave in this manner, too, but their outbursts were fragmented and limited. A group of friends in a bar could deride something based on hearsay, without getting the facts right - then they would move on to the next topic. Now people have transposed this behavior online. What has changed is that the rabble has become huge because online circles engage in mass communication. There is not much a government can do to control online disinformation except hope that common sense will prevail in the end. But at least the government needs to have the tools to clamp down in case things spin out of control, or to have a trail of clues to pin down the culprits in case malevolence turns into criminal behavior. The riots in Urumqi have shown what could happen: first in a factory in Guangdong province and then in the capital of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomus region, instigators spread rumors and lies online. Hordes of netizens became enraged, formed into a mob and eventually spun out of control to unleash brutal violence on the real world. Shouldn't the government then have advanced tools to rein in online content and communications that can cause social or political strife, or disseminate illegal content or facilitate unlawful transactions? I believe it should. But the government should have some safeguards to prevent potential abuse by the regulatory and investigative bodies, too. One way of doing this would be to pass a law to regulate the process, and to practice transparency. If it is carried out in the right manner, I think most netizens would not feel that their privacy is being compromised. The author is an associate in a company that designs nature and culture travel, and offers consultancy in western China. (China Daily 07/10/2009 page9) |