Squaring off with English

Updated: 2012-01-05 07:32

By Xu Lin (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

BEIJING - When Deng Shenyi used a brush to write calligraphy in New York City in 2008, most of the audience couldn't understand the pictographic words.

|

|

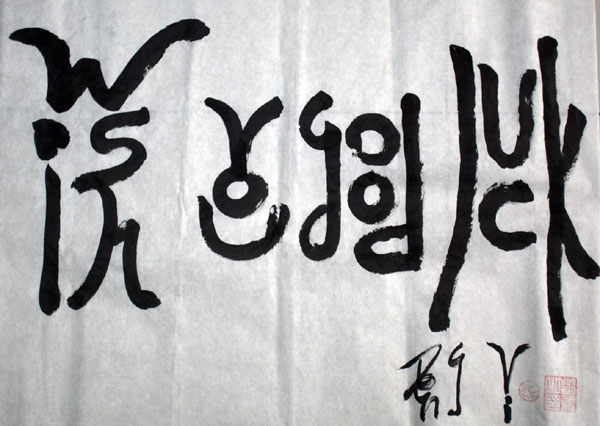

A piece of Deng Shenyi's work which reads "Wish you good luck". Photos by Zhang Wei / China Daily |

"Although they look like ancient Chinese, they are all English words written in a Chinese style," said Deng, a member of the China Association of Inventions.

"On a second look, one can identify these words," said Deng, 49. "After my explanation, the audiences began to understand the words and tried to read them aloud."

He calls this new artistic form "square English", a combination of the English language and Chinese calligraphy.

Like Chinese characters, each square English word is the same size, no matter the number of letters. The English letters are like the parts of Chinese character, and the writing sequence is from top to bottom, and left to right, following the path of Chinese characters.

|

|

"Culture can stimulate the development of society. I'm not changing Western culture, but promoting a Chinese thinking pattern. It's easier to promote Chinese calligraphy among foreigners too," he said.

Since 2008, his works have been exhibited in such places as Beijing, New York City and Las Vegas.

He spent about a month finishing the work of the Charter of the United Nations in square English, which was collected by the UN in 2008. He also wrote the works of English versions of Chinese classical poems, prose and novels.

"It's neat, pretty and saves paper. For the UN Charter, there are 117 pages in the English version, 95 in Chinese, but only 80 in square English," he said.

He said the calligraphy could also be promoted in other languages such as French and German.

"It's very creative. If the special calligraphy is promoted to the world, so is Chinese culture," said Gu Xiangyang, a calligrapher and professor from Peking University.

Deng said the writing of the 26 letters remains pretty much the same as in English, but they are assembled in different ways to make the words diversified.

Square English follows English grammar, too. For example, capitalized words in English remained capitalized.

In addition, Deng divides the words by syllables and writes one after another according to the writing sequence of Chinese characters.

"It's easy to pronounce the word when one sees the divided syllables, especially for Chinese, who are used to the top-to-bottom and left-to-right thinking pattern," he said.

After years of research, Deng has created about 8,000 words in square English, each of which has a fixed form. If he has to write an unfamiliar word, he will first make a draft, to think about the perfect structure of the word.

Deng said the idea struck him when he first came to the United States in 1997 as a visiting scholar.

"My English was so poor that I even had difficulty reading the street names. If I could combine English and Chinese languages, I thought maybe it would be easier to learn English," he said.

At first he scrambled the letters so that the words looked beautiful, but even Americans couldn't understand them.

After numerous failures, he found the right way to write the English calligraphy in 2003.

"For Westerners, square English is art, while for Chinese, it's a new and fun way to learn English," he said.

He said a square English dictionary will soon roll off the press in Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland. The dictionary has more than 8,000 common English words, with Chinese explanations and Chinese pinyin.

He has joined with the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei Technologies to produce square English typewriting software, which will come out in a year or so.

One only has to type the first and last letter of a word, and a list of words will pop up to choose from.

"It's easy to type and avoid mistakes, as you don't have to type all the letters to get the word. People will love it," he said.

Apart from square English, Deng leads a productive life of inventing with more than 160 patents under his belt, about half of which have been brought to market.

He is also adept at both oil painting and Chinese ink-and-water art.

His inventions of a wide variety include an anti-fake liquor bottle that can't be refilled, a wine made of vegetables and herbal cosmetics.

"He is such a versatile inventor and generous about sharing his creations. He doesn't invent for money, but out of interest," said his friend Shen Jie, a member of China Association of Collectors.

Deng said many of his patents have been violated by companies, who stole his formulas in the name of cooperation.

"But I don't bother to file lawsuits. As long as the public benefits from these inventions, I'm happy," he said.