Government and Policy

Lax laws, lack of funds make China's mines deadliest

By YAN JIE (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-05-10 07:36

|

Large Medium Small |

BEIJING - The lax enforcement of safety laws, coupled with inadequate investment in equipment, are partly to blame for China having the world's most deadly coal mines, a senior safety official has said.

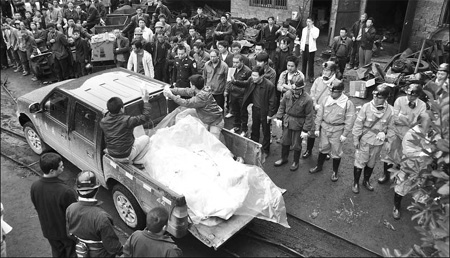

Two miners are rushed to hospital from the back of a truck after being caught up in a gas explosion on Saturday at a coal mine in Enshi, Hubei province. At least 10 miners were killed and another nine injured in the accident. Wang Ting / for China Daily |

China's low efficiency in the use of coal, the country's main source of energy, to feed its booming economy makes it necessary to mine more of it.

This creates the potential for more safety risks and underlines the paramount importance of preventing further mining accidents, Huang Yi, spokesman for the State Administration of Work Safety, said in an interview with the Beijing-based Economic Observer.

|

||||

Safety rules made by the central government have not been carried out at every mine in the country and, in some cases, miners lack the most rudimentary knowledge of these rules, let alone the relevant laws, he said.

For instance, the heaviest fine specified by the national safety laws amounts to 2 million yuan ($300,000). However, not a single coal mine in China has ever incurred such a heavy fine for safety violations, Huang said.

"Fines of 800,000 yuan or 1 million yuan, which have been seen in some areas, are regarded as harsh enough," he said.

Moreover, almost no local government officials have been sacked for unlicensed mines illegally operating in their jurisdiction, an example of the way in which the relevant laws are loosely enforced.

Huang also admitted that Chinese coal mines are poorly equipped to protect miners' lives.

"A few years ago, there was a 70 billion yuan shortfall in the funds available to improve safety at State-owned coal mines," he said.

The deficit was reduced slightly over the past few years, since the central government began to allocate an annual 3 billion yuan to help the mines invest in improving safety conditions.

"But more funds are needed," he added, "as one-third of the equipment at key State-owned mines needs to be replaced."

"China has become a country with the world's most deadly mine disasters as a result of lax of enforcement and insufficient investment," Huang said.

The lack of training for migrants who find work in the mines also adds to the potential for mining disasters.

Of the 5.5 million coal miners in China, about half are migrant workers, while almost all those employed at small coal mines come from rural areas.

"Migrant workers are both perpetrators and victims of accidents," said Huang.

In a recent case, 38 miners were killed and another 115 trapped underground at the Wangjialing Coal Mine in Shanxi province on March 28. Most of the miners who were caught up in the ordeal are migrant workers from nearby villages or other provinces.

If China wants to substantially cut down on mining accidents, the country needs to address the fundamental issues regarding safety and the backwardness of its development model, Huang said.