Society

Opera lover follows thread of tradition

By Cheng Anqi (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-03-24 07:12

|

Large Medium Small |

Peking Opera lover proud of his stage costumes

Beijing - Visiting Feng Changcheng's apartment is like taking a trip to the Peking Opera.

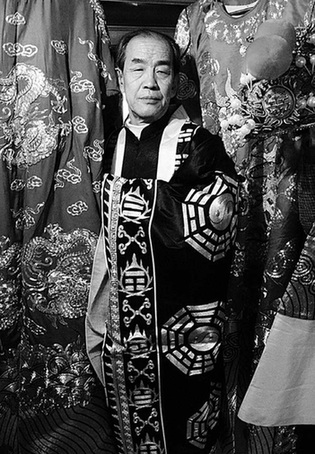

Feng Changcheng with part of his Peking Opera costume collection. |

"Few Peking Opera companies have as many costumes as I have," said Feng, who provided most of the costumes for last year's popular film Mei Lanfang, directed by Chen Kaige.

Over the last three decades, Feng, 64, has amassed one of the largest collections of Peking Opera costumes in the capital, including hundreds of court robes, elaborate headpieces and footwear.

One precious item Feng is particularly proud of is a green mang, a costume for nobles that was made in the 1890s, which he says is "priceless" and he will not sell.

The costume is decorated with two bold and mighty dragons spiraling up from the lower part of the outfit. Gold and silver embroidery threads fill their bodies and their eyes are made of black and white floss.

They look fierce to the untrained eye, but Feng explains that the dragons on the costume are gentle and quiet.

Feng's passion for Peking Opera was stirred in his childhood.

He lived near Taoranting, southern Beijing, where there was an opera theater. Inspired by the spectacle, Feng became an amateur performer when he was 12, and five years later was enrolled by an opera troupe run by an arms factory.

"I usually played Chou, a comic role," he said. "But I could not change my voice successfully and stopped performing."

He later became a backstage assistant, which "offered me a close-up of the exquisite costumes with their kaleidoscope of colors".

He learned the skill of using whiskers or beards, hairpieces, pheasant feathers and water sleeves.

But during the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976), anything traditional came under attack and Peking Opera was no exception. Most troupes were disbanded.

"Hundreds of costumes were piled up in the storehouse and what was worse, they were going to be disposed of. So I sat at the exit and let no one touch them," he said.

However, his persistence failed and they were all sold when the arms factory closed.

Still, Feng's enthusiasm for revitalizing Peking Opera has never stopped. Since the 1980s, Feng has been nosing around the city for old opera costumes in antiques markets.

"If I can't afford them, I make a sketch and have them made to measure," Feng said.

In the past three decades, Feng has put all his savings - more than 500,000 yuan ($73,200) - into purchasing and designing the costumes.

"It seems painful when I look back, but to achieve something you must have a willing heart," said Feng, who also designs costumes and has them made by hand.

Using his glasses, he carefully examines every trace of embroidery.

"Tailored garments on the stage must look real and have an illusion of depth," he said.

With thousands of gold-wrapped embroidery threads, his recently tailored mang robe cost him nearly 6,000 yuan.

But even amid a boom in Peking Opera nationwide, Feng's eyes occasionally exude regret and anxiety.

To show their respect for the art form, performers follow the "worn-rather-than-wrong" principle - even though the garment they pick is worn out, the choice is made according to traditional patterns for the type of role being played.

"Sadly, the standard has never been properly handed down," Feng said, adding that every piece of ornamentation serves to identify and personalize performers, as well as educate audiences.

For example, Zongfa, a brown hairpiece worn by old women, is supposed to be wrapped in a scarf and stands for plain, working-class characters.

"But if other unnecessary ornaments are added in an attempt to beautify the appearance, the original idea is lost," Feng said.

Once, an opera troupe invited him to manage costumes for Jin Yu Nu, the story of a commoner girl who learns of a crook scholar's true colors.

According to tradition, the actress should wear a light-blue upper garment to show the character's low origins. But the actress stubbornly persisted with a pink one and labeled Feng a "preachy advisor".

"That was a terrible breach of tradition and principle. I'd rather be given 10 bad nicknames than have the garments worn the wrong way," Feng said.

"People might want to make improvements by adding new movements and changing appearances," he said. "But they shouldn't aim for reality on such a deep level ... they should rely on traditional rules instead."