Lives of iron forged in tribulation

Due to the combined factors of a job shortage and racism on the West Coast, many Chinese immigrants embarked on a journey that took them to many other parts of the country.

Most died alone, leaving behind nothing but a bunch of unsent letters, and with no idea of the last charitable act performed for them by their compatriots on both sides of the ocean.

The single most evocative item in the exhibition is a bone-repatriation book from 1894, owned today by the China Alley Preservation Society in Hanford, California. The written record, the only such copy found in the history of American Chinese, includes detailed descriptions of the deceased: what Chinese village they called home, how they came to Hanford and at what age.

Usually, the remains were exhumed several years after the initial burial, for the bones to be collected and sent home, to their ancestral villages on the southern Chinese coast. Often the journey was paid for by regional associations or charitable organizations in China, Tung Wah Hospital in Hong Kong being prominent among them.

Such trips home were interrupted in the 1930s and '40s, first by World War II and then by civil strife in China. From 1930, more than 1,500 Chinese immigrants, mostly solitary sojourner-workers, were laid to rest at Mount Hope Cemetery in Boston, Massachusetts. In 2007, members and supporters of the Chinese Historical Society of New England erected a memorial in their honor.

Massachusetts, colonized by the British in the early 17th century, proved to be hostile when the first batch of Chinese arrived by train in the early 1870s, brought in to replace union workers who were on strike at a shoe factory in North Adams, 220 kilometers east of Boston.

The Chinese, unaware of their role as strike-breakers, were met by 2,000 angry people at the train station, before 50 policemen armed with shotguns escorted them to the factory.

The Chinese, realizing they had been duped, left for other places, including New York and New Jersey.

About the same time, 68 Chinese boys and men, aged 3 to 32, arrived in Belleville, New Jersey, recruited by a ship captain, James Hervey, for the laundry business he owned. Hervey had "a deeper understanding of the Chinese through his previous trading with China", said Perrone of the Belleville Chinese Historical Society.

"As home to the first Chinese community on the East Coast, Belleville embraced the newcomers while the rest of the country rejected them."

In January 1871, a few months after the Chinese arrived, they held their first Lunar New Year celebration in Belleville. "New York city didn't allow public Chinese New Year celebrations until 20 years later," Perrone said.

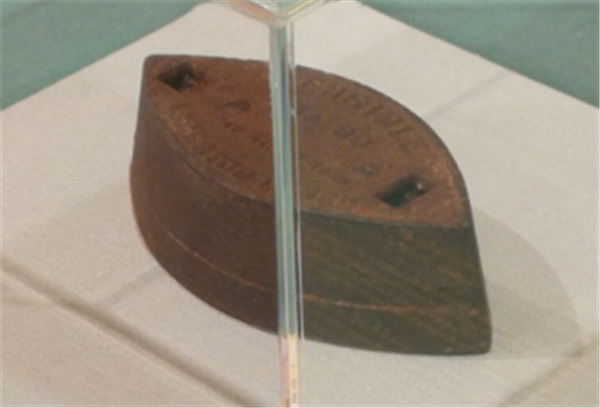

Later that year, the Belleville Chinese Sabbath School opened. A joint venture of Belleville's three churches, including the Belleville Reformed Church in whose cemetery the iron was discovered, the school taught English and Bible study and by its first year enrolled 60 pupils.

Perrone attributes acceptance of the Chinese in Belleville to the town's liberal history. "During the American Civil War, Belleville was staunchly anti-slavery while New York and the rest of New Jersey, although nominally staying within the Union, were sympathetic toward the South."

Tam, the exhibition curator, says Perrone, whose childhood connection with China included going to Chinatown in Belleville to buy fireworks and reading about the adventures of Marco Polo, was far from the only ethnically non-Chinese person interested in the history of Chinese Americans.

"One of the places I went to in preparation for the exhibition was the Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site, a tiny museum of 1,000 square feet (93 square meters), located in a mountainous area in John Day, eastern Oregon," Tam said. "When you go inside, there's an audio guide telling you what it was like in the 1880s. The feeling is visceral."

It is the only stone building in Chinatown in John Day and was once used by Kam Wah Chung & Co, a Chinese general store-cum-herbal medicine shop. John Day was a mining town in the mid-1880s and had the third-largest Chinatown in the US, after San Francisco and Seattle, Washington, or Portland, Oregon, depending on the year.

Tam said: "The Chinese had left a long time ago, but there's a group of people, almost all white, who got to know the former owner of this place-a Chinese doctor famous for his herbal remedies-through their parents and grandparents and decided to honor his memory."