Evolution of a China Solution

China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective

Evolution of a China Solution

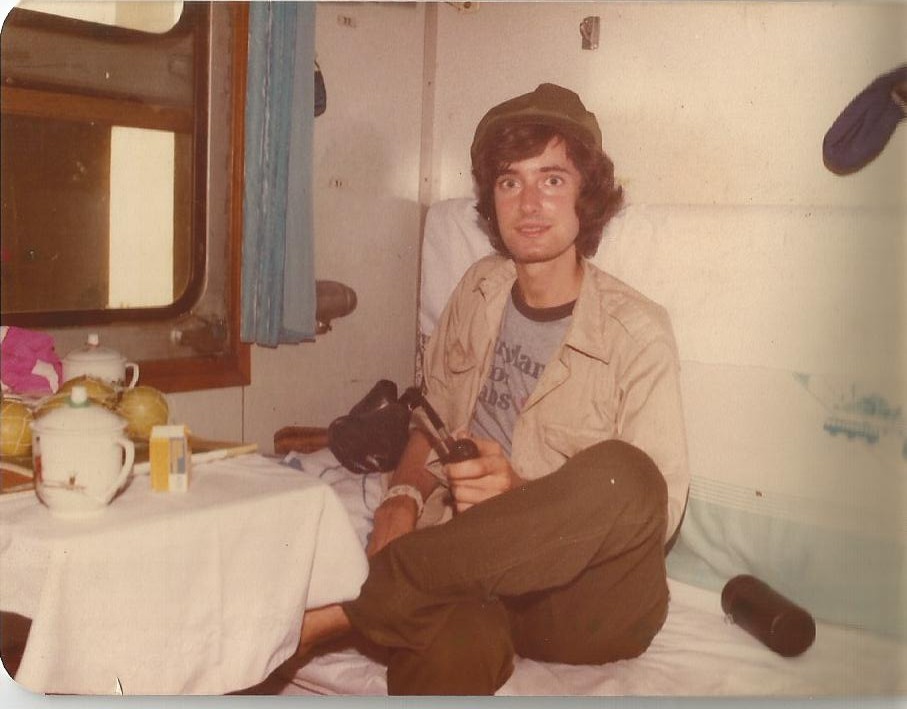

Editor’s note:Laurence Brahm, first came to China as a fresh university exchange student from the US in 1981 and he has spent much of the past three and a half decades living and working in the country. He has been a lawyer, a writer, and now he is Founding Director of Himalayan Consensus and a Senior International Fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

He has captured his own story and the nation’s journey in China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective. China Daily is running a series of articles every Thursday starting from May 24 that reveal the changes that have taken place in the country in the past four decades. Keep track of the story by following us.

I will never forget that day in October 1987, reading the China Daily from my legal office in Hong Kong. On the front page black and white letters spelled the winds of change. At the 13th Chinese Communist Party congress then convening in Beijing, it was boldly declared that China was “socialist” – not communist – and remarkably only “at the first stage of socialism,” moreover adding that the “first stage” would take “a relatively long period of time”. It was a brilliant phraseology --- certainly better than us lawyers could come up with – in shifting the goal posts toward opening the state-planned economy to become a market.

So back in 1987, this new message was not lost on anyone’s consciousness in Hong Kong. For the first time business elite in Hong Kong sensed the dragon awakening. With it they could smell business opportunity drifting in the air. Even the most pessimistic skeptics suddenly looked up from their stock market pages and paid attention to Chinese mainland.

Looking back, it was during the Communist Party Plenum in 1978, that the leadership began bringing common sense into economics, toning down ideology. After three decades of communalism, getting everyone to think out of the state-planning framework was difficult. So by introducing market reforms that could be swallowed in dumpling-sized bites, setting a lower threshold while pushing the goal posts back.

The new persuasive logic went like this: Communism is an ideal, but just a goal. Socialism is more realistic for everyone to attain, while keeping an eye on the goal. The term “communism” was then conveniently not used and “socialism” became the favored lingo.

A decade later at the 1988 Communist Party Plenum, “socialism” became the new lofty goal everyone should strive for but not attain. After his 1992, the rationale was that China is an underdeveloped country, so economic development rather than ideology should take precedence. Everyone transitioned from ideology to pragmatism.

During the 1960s-1970s the debate swung extreme left. During the years from 1978 to 1992, it wavered back and forth (between the “bird fly in a cage” theory and the “open the window let the fresh air in and then swat the flies” theory). After 1992 when real market reforms began, the question was how much to protect the state sector and how much to push the private. That did not change until 1998 which marked a massive five-year transformation of state-owned enterprise and introduction market reforms that mesmerized the world.

There are two Chinese take-away points from the “China solution.” One, there is no one single model to be applied universally. Second, ideologically premised economics is impractical. The fortune cookie message is simple: end the socialist versus capitalist debate, dump the theory and do what works. Lets the market run its course. When it runs out of control they rein it in. If fiscal measures, taxes and interest rates don’t work, adopt administrative measures, fees and quotas. Don’t care about what you call it, as long as it gets a result.

Years ago I tried to explain this way of making policy by coining the term “China Inc.” in a book called China Inc. published by Butterworth-Heinemann. My analogy was to think of China’s core policy-making body as a board of directors of a massive corporation making decisions to cope with market realities while planning their corporate strategies with a five-year horizon. Then think of the legislative bodies functioning as an annual shareholders meeting. Rather than the combative electoral politics of the west that actually forces leaders to become professional politicians working for lobbying interests. In Washington this view or description comparing the political systems was politically incorrect at the time. But eventually the term “China Inc.” became popular being picked up by politicians and journalists alike. Ted Fishman later also published a book called China Inc. By that time the term had become internationally acceptable.

Eyeing the China experiment, other countries across Asia began adopting their own version of this “fusion” economics, mixing tools of market and central planning, sometimes more, sometimes less. Vietnam, Laos and Malaysia have been examples of mixed economies. Each did it their own way, based on their own local circumstances. They sought “sequenced”, step-by-step reforms not by “shock”. The BRICS and G77 take China’s approach seriously. They borrow what is useful and discard what is not. They don’t get hung up on ideology or theory.

China despite all of its problems, demonstrated an alternative is possible by unabashedly using both the tools of market and planning, and transformed the economy from scarcity to over-supply, from poverty to conspicuous consumption wealth. Within two decades China pulled more people out of poverty than any other country in history. But there were also unforeseen costs. Environmental degradation and loss of culture and identity (the very roots of a people’s soul) are examples of what can go wrong when there is over-reliance on economic growth. Stuffing homes with brands did not bring happiness in China, as it did not bring happiness in America either. In both countries conspicuous consumption has created greed, social frustration and distorted values.

China’s experience during the 1980s-1990s taught us that we need pragmatic holistic economics to replace theory and put an end to the dogma of theoretic fundamentalism regardless of whether it is communism or capitalism. Likewise excessiveness today in any form whether neo-liberalism or state capitalism will ultimately work against itself. There is a negative karma effect in any form of extremism – economic or political. Economics should be both pragmatic yet also holistic. We need an economic middle way. Maybe that is what the “China solution” is all about.

Please click here to read previous articles.