Law without lawyers – Reform without economic theory

China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective

Law without lawyers – Reform without economic theory

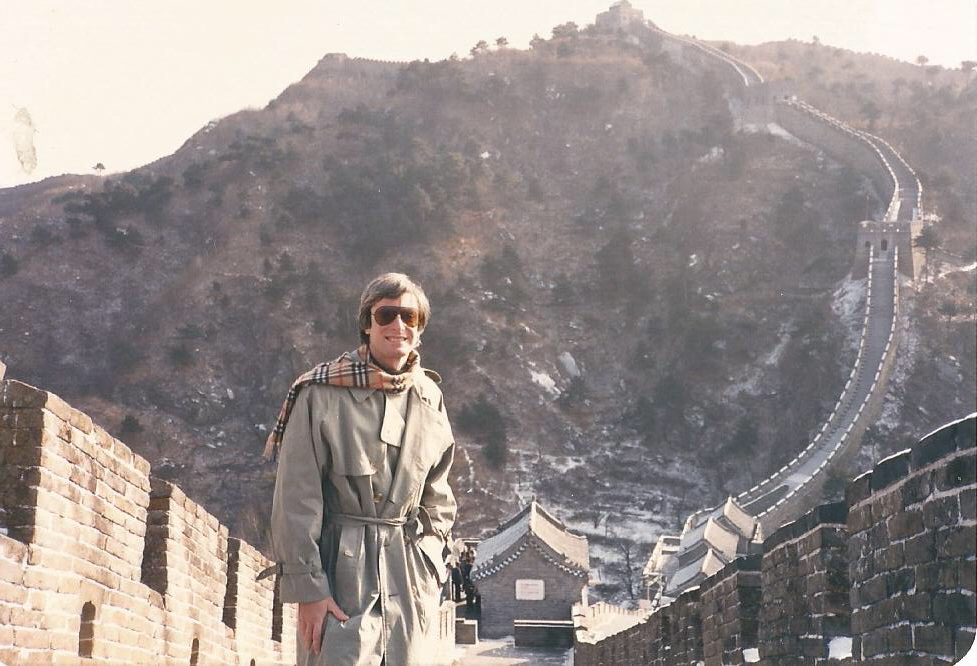

Editor’s note: Laurence Brahm, first came to China as a fresh university exchange student from the US in 1981 and he has spent much of the past three and a half decades living and working in the country. He has been a lawyer, a writer, and now he is Founding Director of Himalayan Consensus and a Senior International Fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

He has captured his own story and the nation’s journey in China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective. China Daily is running a series of articles every Thursday starting from May 24 that reveal the changes that have taken place in the country in the past four decades. Keep track of the story by following us.

During the 1980s, I worked as a lawyer from Hong Kong, commuting each week to our Beijing office, which at that time was in the old Peking Hotel. In those days, just walking through the lobby or coffee shop of the Peking Hotel, it seemed that I knew everyone. Actually the foreign community doing business with China was that small then. China’s legal system was at the nascent stages of development. There were few laws and regulations that were issued to respond to changing conditions. So new regulations, often contradicting each other, were constantly issued to keep up with ever changing conditions. So the real job of a “China trade lawyer” -- a foreign lawyer helping Western businesses enter China -- was to keep up with the changes.

In reality I was more a negotiator than a lawyer. Everything depended on officials approving each step in the long process of making an investment. Bright red stamps were required on all the papers needed. The point was not what the law said, but the approval process. The legal system was actually developing around the investments, not the other way around. Every time a contract was signed and then stamped by the authorities, that contract effectively became the law. As bodies of contracts emerged, the government issued regulations based more on the reality of what was happening rather than as a long-term blueprint. It was an evolving system, and as lawyers negotiating and drafting the contracts, we were actually playing an influential role in the way that system developed.

From the outside looking in, China’s process of reform and opening-up seemed slow, often described by Western observers as “two steps forward, one step back.” As China opened its economy and began to drift away from State planning, there were many unknowns and often reactions that were quite conservative.

From the outside, few realized what was really going on. An internal debate on how to open China’s economy was being thrashed out during the 1980s.

One group pushing reform often quoted an old Sichuan adage, “It does not matter if the cat is black or white as long as it catches mice.” In short, it does not matter if the economic tools are socialist or market, as long as the economy works effectively and efficiently. So let’s be practical, why not open up and kick off a market economy within the context of a socialist system? The more conservative view countered by proposing the “Bird Cage Theory” of economics. The economy could fly but only within the cage of State planning, like a parakeet. So the big question was, does China open the cage, and let the birds fly? In supporting this argument one leader insisted, “If you open the window, a few flies will come in with the fresh air. So what? You can always swat the flies.”

Before China’s reform and opening-up, nobody owned anything at all. To kick off a market economy there had to be ownership, most importantly ownership of land. But how could someone own land in a communist country? Believe it or not, capitalist Hong Kong provided the answer. As a colony, all land belonged to the British Crown. Every parcel was on a 99-year lease. Leases could be freely sold and traded. One of my friends at the time was a Chinese lawyer entrusted with drafting China’s first land law that would later be tested in Shenzhen and the other Special Economic Zones before becoming national policy. The transition was quite simple. Under Hong Kong’s British law, all land belonged to the Crown and a lease was granted for 99 years. People basically could own their flat or apartment, but the land was always under lease. This exact policy was adopted across China. Adopting principles of Hong Kong land law was really a convenient idea for China's leaders. They just replaced “Crown” with “People’s Government.” Instead of the Crown’s land it belonged “to the people” or effectively the government (on behalf of the people). In Chinese mainland one can have an ownership certificate for their apartment, just as in Hong Kong, but never own the land, which is always under leasehold. Borrowing ideas from Hong Kong was easy.

The idea of experimentation based on pragmatism and the practical reality of material limitations was happening in China. This differed so much from Western models of economics that are even to this day very theory dependent and often not practical. China was always looking at what could work, testing it, adjusting it and testing it again. China’s reforms could be described as crossing a river by feeling one rock at a time. It was just so pragmatic.

But outside observers criticized China’s approach as cautious. For Americans it seemed unorthodox. It certainly did not fit in with the “shock therapy” prescription proselytized to the world by American academics at that time.

From the ground, I saw things differently. It was clear a socialist economy in transition could not be shocked into reform. Interwoven problems had to be delinked in some sort of sequence. I remember a Chinese official sitting across a desk from me in his office, wearing black horn-rimmed glasses and a white short-sleeved shirt that hung clumsily over his trousers. He picked up an orange and started to peel its skin with his thumb moving the orange in rotation. The whole skin fell to his desk in spiral layers that were unbroken, leaving the orange held neatly intact between his thumb and forefinger without shedding a drop of juice. I thought about how we Americans eat a Sunkist orange, just tearing it in half and sucking out the juice. The difference was juxtaposed in my mind.

Holding aloft the orange like Atlas holding the earth, the official declared, “Opening up China’s economy must be done like this!” Otherwise, the entire social structure would rip and unravel with the juice spilling everywhere. That was his point.

Please click here to read the previous episode.