From Scarcity to Market – 1981 Revisited

China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective

From Scarcity to Market – 1981 Revisited

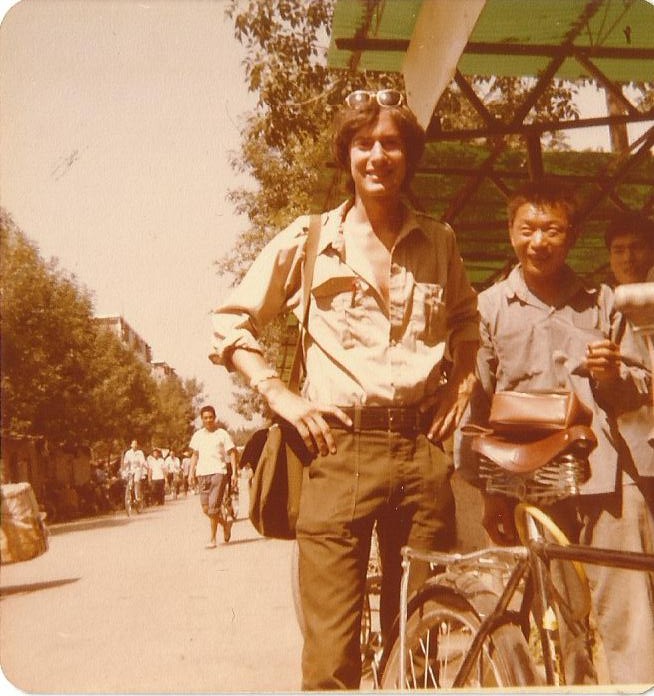

Editor’s note: Laurence Brahm, first came to China as a fresh university exchange student from the US in 1981 and he has spent much of the past three and a half decades living and working in the country. He has been a lawyer, a writer, and now he is Founding Director of Himalayan Consensus and a Senior International Fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

He has captured his own story and the nation’s journey in China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective. China Daily is running a series of articles every Thursday starting from May 24 that reveal the changes that have taken place in the country in the past four decades. Keep track of the story by following us.

In Tianjin in 1981, across from the entrance gate of Nankai University, there was a fledgling free market. Until then, there were no other choices. People had to queue every day to buy food because they did not have refrigerators. State-distributed food supplies were sparse and irregular; state-store employees dour and irascible. Each day people lined up at those state-run stores with tickets to exchange for staples. Even with money, you could not buy rice or dough without quota-rationed coupons.

However, across the street the free market farmers had all sorts of fruits and vegetables. There was variety. People could see the difference standing there. The offer grew each day. However at the state stores, every day, everywhere, goods on offer were always the same — that is, if anything was available.

A forlorn innocence prevailed. Just as years later I would find “street economics” more important than theory, I found life in Tianjin’s streets more important than studying in the classroom. At night I wandered the streets performing simple magic tricks my father taught me as a kid. It was a way to meet all sorts of people in the street and practice my spoken Chinese, which improved dramatically. People gathered – sometimes in big crowds -- laughed and asked me to perform again and again and again. They never seemed to get tired of watching the same tricks.

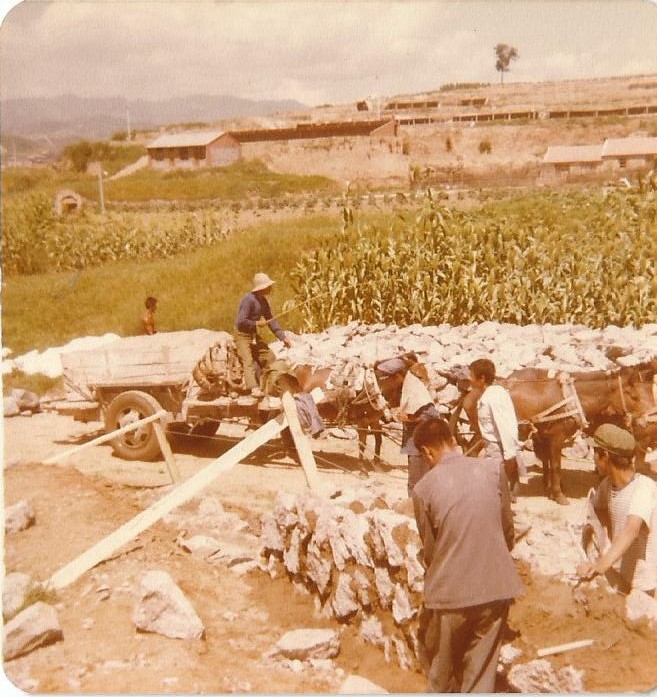

In 1979, a tiny experiment occurred in far-off Anhui province. Against the backdrop of nearly three decades of communalization, 18 village families agreed by contract they would pool resources. As simple as it sounds, it was a bold move against the policies of that time. They agreed among themselves they would turn over to the state only their quota requirement of the crops harvested. Each family could sell the rest and retain the proceeds. Wan Li, then the provincial party secretary, supported their move. It was later dubbed the “household responsibility system.”

This little experiment, allowing one small group the right to grow their own rice and cabbage, deeply changed China.

Wan Li himself rose to become one of the highest-ranking leaders in the country. Our paths would cross. One decade after I arrived in China as a student, Wan Li stood at the height of his power, as Chairman of the National People’s Congress. He gave me an audience in the Great Hall of the People.

As Wan Li received me in the hall, in one of those vast dreary rooms with overstuffed sofas and dusty red curtains, he had one burning question: how to transform China’s debt-ridden rusty state-owned enterprises into global conglomerates that could compete with American corporations for international markets? Five years later I would be on the ground in Anhui province, where his own reforms first began, working on a blueprint for the “corporatization” of China’s state-owned enterprises.

A decade and a half later, what then seemed like the far-flung dream of an old revolutionary became a reality that would shake the economic order of our planet.

Wan Li’s early experiment of household responsibility system in Anhui had ushered a new Chinese phrase. People in the street were whispering the words “free market.” But what did it really mean? A few bold peasants brought vegetables and peanuts folded in rough cloth — because they had no bags. Squatting on the curbside, they sold them for cash. Remarkably, they kept the money. People talked about it excitedly.

It was the beginning of the free market. But nobody dared use the word “market economy.” The free market was on the fringes of China’s economy. It was something on the curbside.

In China, every single item was used and reused. Coming from America, where so much in the way of resources — from energy to food — was wasted, I was both shocked and getting educated!

Before coming to China, I had studied at Duke University. I remember one lunch at the cafeteria, a student from Taiwan pointed to an American wolfing down a massive steak sandwich. “There is more meat between those two pieces of bread than my whole family of six would enjoy at dinner,” she said. The juxtaposition in values cut into me like a knife. At Nankai University in Tianjin, when a pen ran dry students found a way to put water in it and make more ink come out; every scrap of paper was written on until there was no white left. Nothing in this society was wasted.

When the student cafeteria served scraps of pork fat with rice, we were very happy, because there was no meat on the market in those days. I remember being with a classmate when we found something unusual. A small roasted baby chicken in the window of one of these state-run stores. We had not seen one before. Little did we realize that skinny chicken, roasted and hanging upside down on a hook, indicated economic reforms were already at work.

We bought and ate it, joyful to have something that simple.

Please click here to read the previous article.