Soon, townspeople were complaining to Bennington officials and employees at the Apple Barn, a roadside store and gift shop where the orchard's apples are sold.

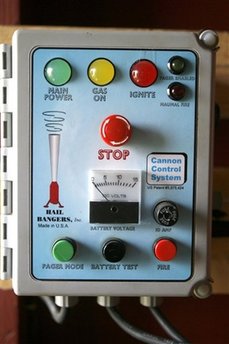

The control panel for the hail cannon in Bennington, Vt., Wednesday, Sept. 3, 2008. The owner of Southern Vermont Orchards, Harold Albinder, believes he has found a novel way to protect his apples from hail damage, which is snickeredy by scientists and swore by neighbours. [Agencies]

|

"I had a woman come in here and yell at my employees," said Lia Diamond, Albinder's daughter, who runs the store. "There were phone calls. Very unkind."

Connors erected a hand-lettered "No hail cannon" sign on the road leading to the orchard and lobbied town officials to silence it.

"It comes off of the mountain, and we even hear aftershocks from the blast," he said. "I'm from Brooklyn originally, and I have a pretty good sound filter. But I moved to Vermont for a different life, and here it is, more sound pollution following me up here."

Three times, police cited orchard manager Lee Herring, who erected an L-shaped barrier out of 800 hay bales to try to muffle the noise. It wasn't enough. The booms still exceeded the 45-decibel nighttime limit of Bennington's noise ordinance, and Albinder agreed in the middle of the summer to stop using the cannon for now, in exchange for dismissal of the citations.

Albinder argues his cannon is protected under Vermont's right-to-farm law, which exempts certain agricultural practices from local ordinances. But whether that argument would succeed in court is unclear.

In 2003, the Vermont Supreme Court said the right-to-farm law didn't protect an orchard from a neighbor's lawsuit over noise from its pallet-manufacturing operation because the orchard wasn't making the equipment before homes began springing up nearby.

"If a farm changes its practices to create a nuisance, the right-to-farm law does not necessarily protect that new farm practice," said Phil Benedict, a state agriculture official.

Albinder said he will ask the Legislature to override the town ordinance.

"This is my livelihood," he said.