Painter’s Trouble

On August 17, 2010, the Beijing Dongcheng District People’s Court heard a case brought by painter Zhao Menglin (Plaintiff) against the Beijing Arts & Crafts Group Co. Ltd. and the Fujian Fuguihong Culture Development Co. Ltd. (Defendants) for copyright infringement.

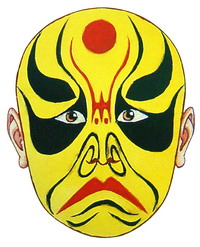

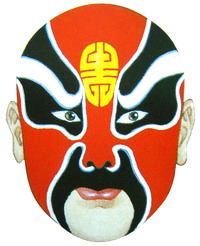

Zhao testified that, he finished the album of paintings Facial Makeup in Peking Opera in 1992. The album of paintings consists of 272 types of Peking Opera facial makeup and some figure paintings featuring the Peking Opera. Zhao’s lawyer found that eight kinds of facial makeup were used by the two defendants on their porcelain works and subsequently filed suit against them. The defendants argued that the plaintiff’s facial makeup lacked distinctiveness and thus could not enjoy copyright protection.

It is not the first time Mr. Zhao has brought actions on the grounds of copyright infringement. Previously, he had sought relief from South Beauty, Microsoft, Amoi Electronics and many other large companies. Zhao’s lawyer said, “Over the years, I have helped him file dozens of lawsuits. However, I estimate that those dozens of proceedings only account for less than 1% of the total actual infringements. ”

As a kind of folk art, whether the Beijing Opera facial makeup has distinctiveness and whether it should be subject to copyright protection has become the focus of debate in each case. The Beijing Opera facial makeup, which is rich in historical and cultural innovation, faces unprecedented challenges.

Embroiderer’s Puzzle

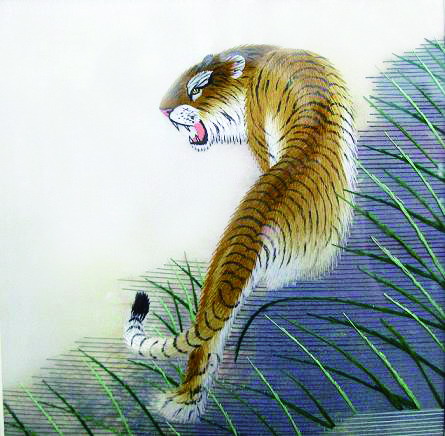

New challenges are not only faced by the Peking Opera. The Suzhou embroidery The Drunken Beauty was also involved in a copyright infringement action. The Shanghai Chinese Quintessence Art Co., Ltd. (Plaintiff) sued Suzhou Goulswon Handcraft Co., Ltd. (Defendant) for using Liu Linghua’s famous work The Drunken Beauty as a sample without authorization. The Goulswon Company produced and sold The Drunken Beauty embroidery, which was regarded by the plaintiff of copyright infringement. The defendant argued that the embroidery work was rough in quality and not produced by the Goulswon Company. Nevertheless, since the defendant could not provide additional evidence of non-infringement, the first instance court ruled that the defendant’s action had infringed the copyright of the plaintiff. The defendant appealed. During the appeals hearing, the dealer, Beijing Ya Bo Jia Shang Culture Development Co., Ltd., admitted its infringement. The case was eventually settled through conciliation. According to incomplete statistics, Suzhou embroidery artists have been successively sued for copyright infringement over the last two years.

Does the process of embroidering which replicates paintings belong to a recreation? How to define the copyright protection involved in that process? Suzhou embroidery, which has a history of 2,600 years, also has to face the challenge of copyright infringement.

The Application of Copyright Law

Most of the traditional folk arts including Peking Opera facial makeup, embroidery and paper cutting art which survive the tide of industrialization and maketization are often trapped in the vortex of intellectual property issues. Whether they positively safeguard their rights or passively respond to the suits, the traditional folk arts which carry the unique cultural heritage face the same problem - how to adapt to the modern legal environment and how to achieve a healthy and sustainable development.

“This case draws a seemingly simple but very serious topic: how to clearly define the copyright infringement issues involved in the succession and development of intangible cultural heritage such as embroidery,” said Zhu Jiechun, the presiding judge of the IP Division of the Suzhou Intermediate People’s Court and the judge of the Suzhou embroidery infringement case. “The focus of the problem is laid on the doubt whether the embroidery work featured with the Beijing Opera facial makeup enjoys copyright protection. Up now, the insiders have reached a consensus that the copyright should be recognized on the embroidery works,” said Zhang Zhenye.

China’s Copyright Law stipulates, “Measures for the copyright protection on works of folk literature and art shall be established separately by the State Council.” Since then, although the authorities had held several meetings and conducted a wide range of research to discuss in depth the legal protection of folklore works, no related regulations were instituted. How to define folk literature and art works and how to protect such works have become the concerns of academic and judicial organs.

Cognizance on Infringement

China IP consulted with Feng Gang, the acting president of the IP Division of the Beijing No.2 Intermediate People’s Court. As to the infringement of such cases, Feng proposed the concept of “Copyright of Folk Art,” that is, in the process of creation, if a work was bestowed with unique characteristics and connotations, it thus obtained “Copyright of Folk Art.” In determining the copyright issues of traditional art works, the judicial point is based on whether the works are new creations or simple reproductions. Although Peking Opera facial makeup originates from folk art, the painter endows the work “Copyright of Folk Art” which thus enjoys copyright protection. Embroidery as an art form is a kind of carrier of paintings. Though the embroidery is particular about the stitch and silk fineness, it is a copy of a painting, and thus is judged as a violation of the painter’s copyright.

A copyright infringer always makes some changes on the involved works. Therefore, the identification of infringement in practice is an extremely complex process. Judge Feng raised the concept of “access plus substantial similarity.” In judicial practice, copying can be divided into simple copying and complex copying. The latter is hard to define. The law, in an institutional sense, can only define the core conceptions in a uniform definition. The marginal details represent ambiguity and are hardly defined by laws. As for the cognizance on the infringement of traditional arts, it is also a highly technical issue. It is easy to see that copyright issues have become unavoidable in traditional folk arts. On one hand, the collision between thousands of years of history and the modern legal system is testing the vitality and adaptability of traditional folk arts. Conversely, the legal awareness of the public should be increased and the emphasis on copyright should be strengthened. Reflections and reform within the industry need efforts from all walks of life. Whether there will be changes in the current pattern and whether traditional arts can walk out of the shadow of copyright disputes, will perhaps be answered in time.

(Translated by Sarah Luo)