Global AI governance essential in a divided world

Artificial intelligence is the new arena for global political conflicts. Once discussed primarily in terms of innovation and efficiency, AI is now framed in the language of sovereignty, security and geopolitical power. Governments increasingly speak of "AI sovereignty" and "data sovereignty" with the same gravity once reserved for territorial integrity or, more recently, energy security.

In November 2025, some 900 policymakers and industry leaders gathered at the summit on European Digital Sovereignty but couldn't deliver meaningful new initiatives. This is not surprising because AI sovereignty is, in essence, impossible.

Even so, countries continue to believe that control over data, algorithms and computing infrastructure is a determinant of national influence. This sovereignty race raises a troubling question. In seeking to secure their technological futures, are countries inadvertently fragmenting the global cooperation on which AI's long-term benefits depend?

The fear of a fractured AI world is no longer hypothetical. We can already see the outlines of competing technology blocs. Export controls on advanced chips, restrictions on cross-border data flows, divergent regulatory regimes and competing standards for "trustworthy AI" are hardening into structural divides. Just like the splintering of global internet rules, AI risks becoming governed by incompatible technical, legal and ethical frameworks.

There are powerful reasons for fragmentation. AI systems are dual-use technologies, critical not only for economic competitiveness but also for military, surveillance and intelligence capabilities. States worry — often with good reason — that dependence on foreign AI infrastructure or datasets creates strategic vulnerability. The response has been a turn inward: data localization, national cloud infrastructures, domestic large language models and public funding programs framed as sovereignty projects.

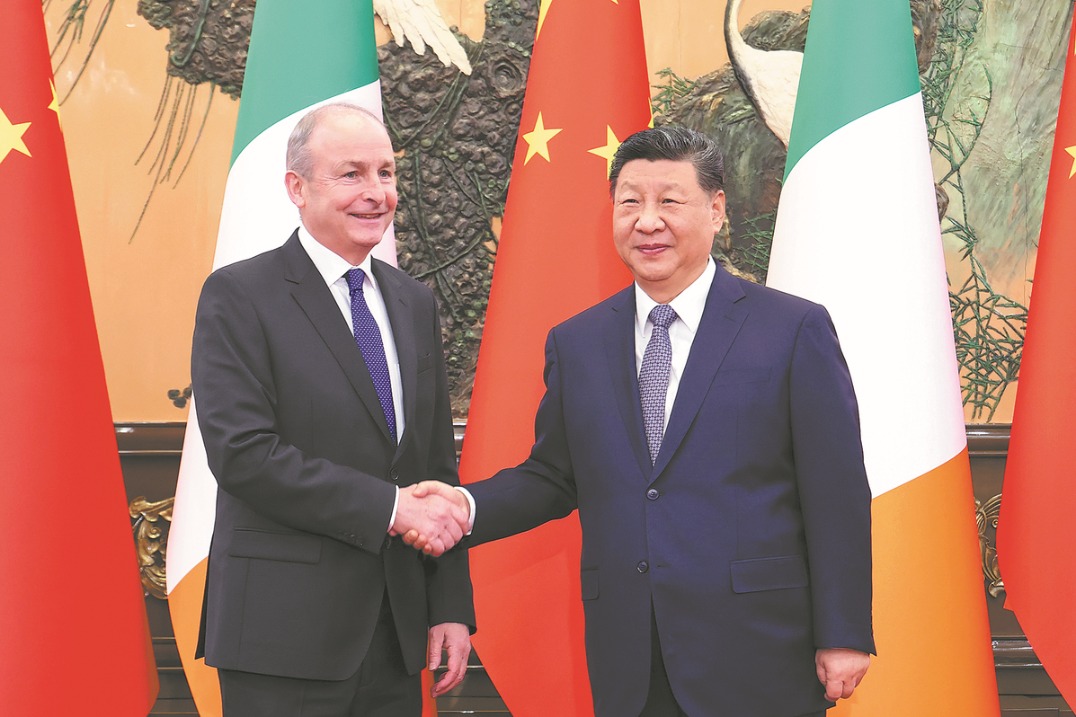

China's emphasis on secure data governance, the European Union's push for "digital sovereignty" through regulation, and the United States' use of export controls to protect its technological edge all reflect the same underlying logic: AI is too important to leave to global market forces alone.

A world divided into rival AI blocs would be inefficient and ultimately less safe. AI systems do not respect borders: models trained in one country are deployed in another; datasets are globally sourced; harms caused by algorithmic bias and disinformation spread transnationally.

Fragmentation would not eliminate these risks, but would make them even harder to manage by reducing transparency and shared oversight. The question, then, is not whether countries should protect their interests, but how they can do so while preserving space for cooperation.

One way forward is to distinguish between strategic control and operational openness. It's reasonable if countries insist on domestic control over critical infrastructure, sensitive datasets or national security applications. But there is little justification for fragmenting areas where cooperation clearly serves collective interests, such as AI safety research, standards for robustness and interoperability, environmental impacts of computing or governance of frontier models with systemic risks.

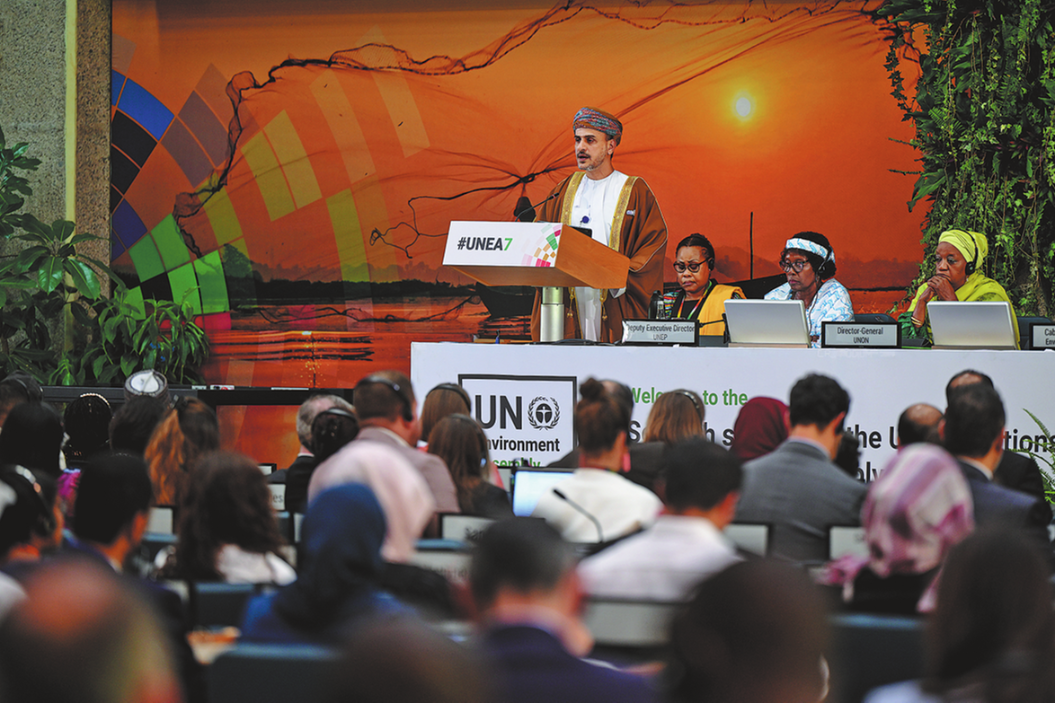

The global AI safety summits point to both the potential and the limitations of this approach. While such forums acknowledge that certain risks, such as loss of human control or large-scale misuse, are shared, they remain largely voluntary and politically cautious. Declarations are easier to pass than institutions are to build.

A deeper problem is the institutional vacuum. Existing global governance structures are ill-suited to AI. Traditional treaty-making is slow, while AI development moves at extraordinary speed. Many international organizations lack technical expertise, clear mandates or political backing. Meanwhile, standard-setting bodies, where much of the real governance happens, are dominated by a small group of countries and firms, reinforcing perceptions of imbalance.

Geopolitical mistrust compounds the difficulty. In an era of strategic rivalry, cooperation is easily framed as a concession, and transparency as a risk. Even basic guardrails, such as information sharing about powerful models or common definitions of systemic risks, become contentious issues.

Here, a Chinese proverb offers guidance: "Lookers-on see more than players". So while the players — diplomats and policymakers — may be lost, the watchers — academics and AI experts — have a crucial role to play. They must guide debates, identify risks and chart pathways forward that protect rights while enabling innovation.

History reminds us that sovereignty and cooperation are not opposites. Arms control regimes, environmental treaties and global trade rules all emerged from periods of intense competition. They succeeded not because countries abandoned sovereignty, but because they recognized that uncoordinated action would leave everyone worse off. Cooperation is an exercise of sovereignty, not its antithesis.

AI governance requires a similar reframing. The question should not be "Who controls AI?" but "Which aspects of AI require shared rules to prevent collective harm?" and "Which systemic risks should we address and mitigate together?"

That shift in strategy and tone allows space for plurality in values and systems, while still anchoring cooperation in pragmatic precaution. For China and other major AI players, this is also an opportunity. Leadership in AI governance today is not only about technological capability, but about institutional imagination. In a fragmented world, the most influential actors in the long run will be those who can bridge divides, not deepen them.

The author is inaugural professor of innovation, theory and philosophy of law and head of the Department of Theory and Future of Law at the University of Innsbruck in Austria. He also leads research programmes at the Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society in Berlin and the Leibniz Institute for Media Research in Hamburg, Germany.

The views don't necessarily represent those of China Daily.

If you have a specific expertise, or would like to share your thought about our stories, then send us your writings at opinion@chinadaily.com.cn, and comment@chinadaily.com.cn.