A cup full of meaning

The character for tea embodies philosophy and heritage, proving language can be steeped just like leaves, Zhao Xu reports.

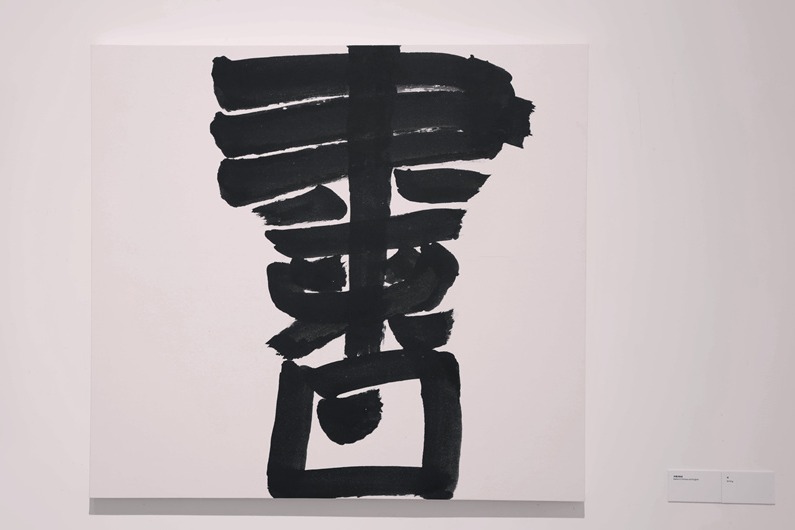

For many of the billions of tea drinkers around the world, Chinese tea is no stranger. Yet, few realize that the character "茶", meaning "tea", carries within its strokes the philosophical spirit that has anchored the Chinese people's enduring passion for the drink since it was first brewed in the 2nd century BC.

"The character has three parts — the upper, middle, and lower," says Shi Linlin of the Center for Language Education and Cooperation, an agency under the Ministry of Education dedicated to promoting Chinese language education and cultural exchange worldwide.

"The upper and lower components represent grass and wood respectively, while the middle stands for a person," she continues. "A figure standing between grass and wood evokes the image of a tea-leaf picker. If you think about it, humans savor tea and are nourished by it — the very essence of nature, as the Chinese believe."

As Shi spoke, she stood at the center of a mini-exhibition on China's tea culture, distinguished by a subtle yet clever linguistic focus often missing from similar displays. "Culture provides an entry point to language learning, and we ensure it is presented with an outsider's perspective," she explains, pointing to the exhibition's note on how used tea leaves can be used in papermaking — a sustainable idea that broadens its appeal.

The exhibition was part of the World Chinese Language Conference, held in Beijing from last Friday to Sunday. Drawing participants from around the world who are closely involved in Chinese language learning and teaching — many of them heads of Confucius Institutes, a Chinese educational organization that promotes Chinese language and culture abroad — the event offered a rare opportunity for story-sharing and provided insight into how language learning can be enriched through cultural context, innovative teaching methods, and dialogue.

"Strong family ties — that's what I find most endearing about Chinese culture," says Alessandro Tosco, Italian director of the Confucius Institute in Sicily, a region of Italy renowned for its extended family networks, multi-generational households, and enduring traditions that deeply shape local life.

A researcher of Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) Chinese opera, Tosco draws careful comparisons between the operatic traditions of China and Italy, focusing on the differences between Chinese and Italian tragedies, the latter rooted in ancient Greek theater. "What I've found is that Chinese tragedies, deeply influenced by Buddhism and the concept of cyclical life, soften the weight of the drama while imbuing it with a sense of resilience," Tosco explains. He ensures that his organization runs events on two tracks — one for general language learners and the wider audience, and another for academics engaged in deeper scholarly exchanges.

"With language learning, you know where it begins, yet rarely where it will end," says Tosco, who has ventured into an academic path few have dared to tread.

"Italy is a country with a rich artistic tradition, which makes it naturally receptive to Chinese culture, itself deeply rooted in artistic and cultural heritage," says Wang Qin, the Chinese director of the Confucius Institute in Sicily. Typically, a Confucius Institute has both Chinese and local directors and is established within a local university, with support from a Chinese partner university.

Wang says last year, the institute organized an event in which every participant had their name written in Chinese calligraphy. "More than 30,000 people took part, which is quite remarkable given that the area is not particularly densely populated," she says.

"Many have regarded Chinese calligraphy as part of the broader Chinese tradition of ink-and-brush painting, which is precisely how our ancestors perceived it," she continues, citing a theory clearly articulated by leading literati artists from ancient China: "Painting and calligraphy share the same origin".