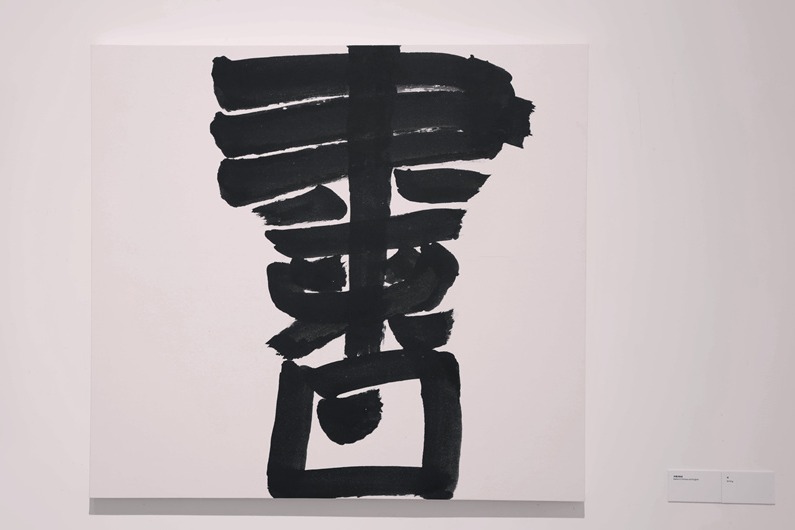

A cup full of meaning

The character for tea embodies philosophy and heritage, proving language can be steeped just like leaves, Zhao Xu reports.

Chen recalls one student remarking that Chinese, with its four tones, seemed to unfold like music. Another became so enthralled by Chinese television dramas from the 1990s — a decade of profound social transformation — that she eventually translated many of them into her native Italian. "Just recently, a Russian student donated a table tennis table to the university — a nod to a sport he came to love in China," says Chen. "Now married and building a life in China, he hopes one day to teach the game to his children."

Reflecting on the next generation, Chen notes a rising tide of overseas Chinese sending their children back to immerse themselves in the language and culture of their forebears. "We call it 'searching for the roots'," he says. "After years of forging lives far from home, these immigrants are turning back, determined that their children reclaim what they have missed so far — a living thread that ties them to the land of their ancestors."

History has never failed to leave its mark. Among the eight Confucius Institutes SISU has helped establish, one stands in Samarkand, Uzbekistan — an ancient Silk Road crossroads. It was along this great web of overland routes, as well as the mountain paths later known as the Tea-Horse Road linking Yunnan and Sichuan provinces to the Xizang autonomous region and beyond, that China's prized tea first traveled westward. Maritime trade would later carry it even farther.

Tea's journey was not only of leaves, but of language. The global variety of words for tea — tea, the, te, and chai — mirrors the routes by which it spread. The Mandarin pronunciation cha moved across Central Asia, the Middle East and Russia via the Silk Road, evolving into chai. In contrast, coastal dialects in Fujian and Guangdong used the form te, which was carried by sea through ports frequented by Dutch traders and into Europe. Thus, languages supplied by land inherited versions of cha, while those supplied by sea adopted forms of te — a linguistic map of ancient trade etched into the modern vocabulary of tea.

"A single word can throw open a window onto the vastness of history — reminding us that to tell China's story is, inevitably, to tell the world's," Chen says.

The mini tea-culture exhibition on view at the conference included a panel of Chinese sayings — ancient and modern — centered on tea. One reads, "Tea leaves open themselves in hot water; the mind, too, must loosen its grip on trouble."

Another offered a gentle reminder of tempo: "Food may be taken in haste, but tea must be savored slowly — that is the Chinese way."