Finding her wings: Sudanese student soars with studies

"Every time, I've grown stronger amid lonely wandering.

Every time, even when wounded, no tears betray my heart.

I know I've always had a pair of invisible wings,

Carrying me high, flying beyond despair …"

With a clear, melodic voice, 18-year-old Sudanese girl Ghofran Shamseldin sang a Chinese song before a vast audience in Xi'an, Shaanxi province. Its lyrics had long given courage to many, but in her, they found their truest echo. Losing her sight to a genetic disorder, Shamseldin had searched through darkness for those invisible wings — and found them.

"I decided to learn Chinese in high school after reading an Arabic translation of Yu Hua's novel To Live," she says.

Published in 1993, the work, widely considered one of the most influential modern Chinese novels, tells the lifelong travails of an ordinary peasant, against the backdrop of sweeping upheavals in 20th-century China. Having lost nearly everyone he loves — his parents, wife, son and daughter, each to fate, hardship or accident — the protagonist continues toward the end of the book, embodying the stark, haunting truth at the heart of the novel: that survival itself, however lonely and painful, is the deepest form of perseverance.

At that time, Shamseldin, who had always known that she would one day lose her sight, was still able to see. Yet, her condition deteriorated over the next few years: while a freshman at the Chinese Language Department of the University of Khartoum, she was only able to discern the strokes of a Chinese character by shining a torch onto the book's pages. "That fleeting window let me glimpse the shapes of Chinese characters. Though I would spend the rest of my life learning the language by ear, I have never forgotten their forms," says Shamseldin.

Yet, occasionally, she would still need to write, like when she wanted to give one of her Chinese teachers a card written by herself. "I asked a classmate to hold my hand and make the moves — I felt that anything less than that would fail to express my gratitude," she says. The same teacher gave her a Chinese name, Li Can — Li being a common surname while "Can" means "splendor".

"Sincerity — that's what I felt from my students," says Yao Xiaolin, who taught at the University of Khartoum's Chinese Language Department and the Confucius Institute in Khartoum from 2015 to 2020. Affiliated with the Chinese government, the Confucius Institute is a public educational organization that promotes Chinese language and culture abroad, often in collaboration with foreign universities. Sudan's first institute, jointly established by the University of Khartoum and Northwest Normal University in Lanzhou, China, opened in November 2009 — six years before Shamseldin enrolled.

"They would give small gifts — cards, cakes, handmade crafts — simple, even humble, yet carrying the deepest, most genuine human emotions."

In 2017, when Shamseldin traveled from Khartoum to Xi'an for a major Confucius Institute conference, Yao was by her side. She watched as Shamseldin sang, and as the final notes faded, the audience held its breath in silence — before breaking into a wave of resounding applause.

"The support Shamseldin received from her parents was rare among female students. Most Sudanese parents, being relatively conservative, balk at the idea of their daughters venturing into an entirely new world," says Yao.

Between 2019 and 2024, Shamseldin spent a total of two years in China as an exchange student. While she needed help navigating the campus or venturing out into the streets, she managed all the cooking and laundry in her dorm independently. "My new classmates and friends had no idea about my condition — it isn't immediately visible — so each time I had to find a way to let them know. It's not always easy but in doing so, I learned self-acceptance."

In April 2023, civil war broke out in Sudan and has raged ever since, unleashing a humanitarian catastrophe — millions displaced, rampant food insecurity and the collapse of essential services, including education.

Tian He, who led the Confucius Institute in Khartoum from 2012 to 2017, was back in China coordinating the evacuation of its Chinese staff members when the conflict erupted. He still remembers it vividly. "I was on the phone with our colleagues there constantly, and through the receiver I could literally hear the whistle of bullets," he says.

Shamseldin returned to Sudan in July 2024, but war forced her family to keep moving until they settled down in May this year. For the past three months, she has been giving online Chinese lessons to students from the Bahri College in Khartoum, which also has a Chinese language department.

"Thanks to modern technology, I can prepare all my class PowerPoint presentations on my own," she says, admitting that her dream is to work as a Chinese-Arabic simultaneous interpreter at international events and share her story with a wider audience.

While studying in China as an exchange student, Shamseldin experienced her second "reading" of To Live — this time through audiobook. "Reliving the struggles of the protagonist urged me to reflect on how I should truly live my own life," she says.

Today's Top News

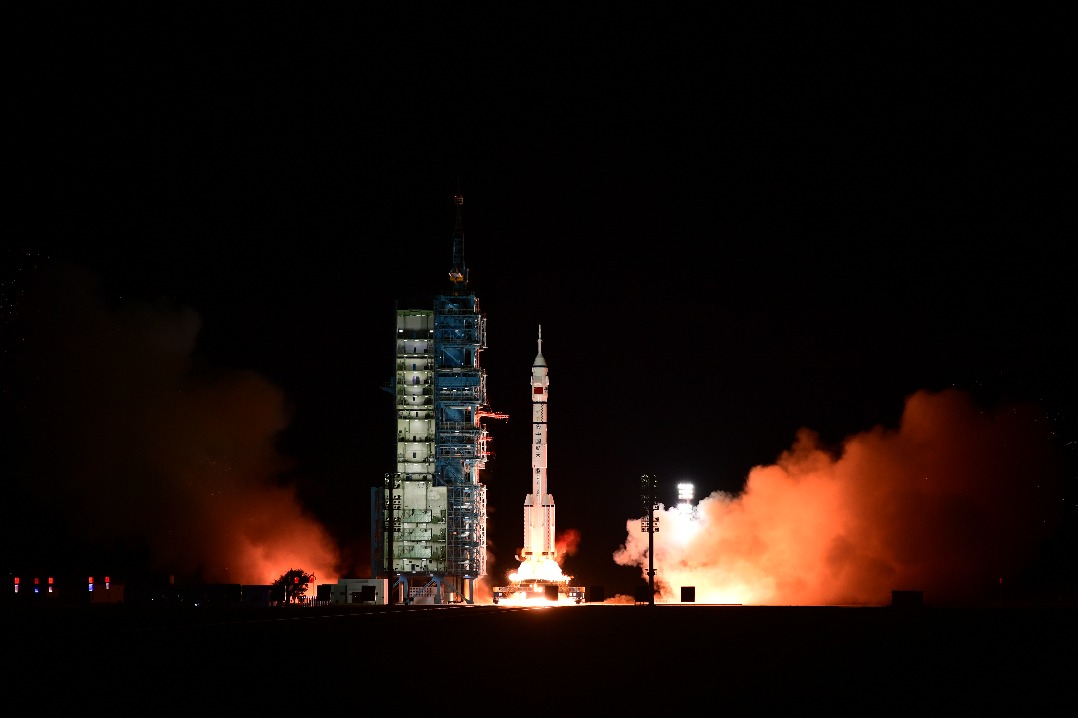

- Shenzhou XXI blasts off, on way to space station

- Xi: Join hands, strengthen links

- Sound, steady growth of China-Canada ties stressed

- Tokyo called on to foster correct perception

- Beijing, Bangkok to align growth strategies

- Call for openness and inclusivity for dynamic Asia-Pacific: China Daily editorial